This is a special post for quick takes by Eric Neyman. Only they can create top-level comments. Comments here also appear on the Quick Takes page and All Posts page.

People are underrating making the future go well conditioned on no AI takeover.

This deserves a full post, but for now a quick take: in my opinion, P(no AI takeover) = 75%, P(future goes extremely well | no AI takeover) = 20%, and most of the value of the future is in worlds where it goes extremely well (and comparatively little value comes from locking in a world that's good-but-not-great).

Under this view, an intervention is good insofar as it affects P(no AI takeover) * P(things go really well | no AI takeover). Suppose that a given intervention can change P(no AI takeover) and/or P(future goes extremely well | no AI takeover). Then the overall effect of the intervention is proportional to ΔP(no AI takeover) * P(things go really well | no AI takeover) + P(no AI takeover) * ΔP(things go really well | no AI takeover).

Plugging in my numbers, this gives us 0.2 * ΔP(no AI takeover) + 0.75 * ΔP(things go really well | no AI takeover).

And yet, I think that very little AI safety work focuses on affecting P(things go really well | no AI takeover). Probably Forethought is doing the best work in this space.

(And I don't think it's a tractability issue: I think affecting P(things go really well | no AI takeover) is pretty tractable!)

(Of course, if you think P(AI takeover) is 90%, that would probably be a crux.)

One additional point, as I'm sure you know, is that potentially you can also affect P(things go really well | AI takeover). And actions to increase ΔP(things go really well | AI takeover) might be quite similar to actions that increase ΔP(things go really well | no AI takeover). If so, that's an additional argument for those actions compared to affecting ΔP(no AI takeover).

Re the formal breakdown, people sometimes miss the BF supplement here which goes into this in a bit more depth. And here's an excerpt from a forthcoming paper, "Beyond Existential Risk", in the context of more precisely defining the "Maxipok" principle. What it gives is very similar to your breakdown, and you might find some of the terms in here useful (apologies that some of the formatting is messed up):

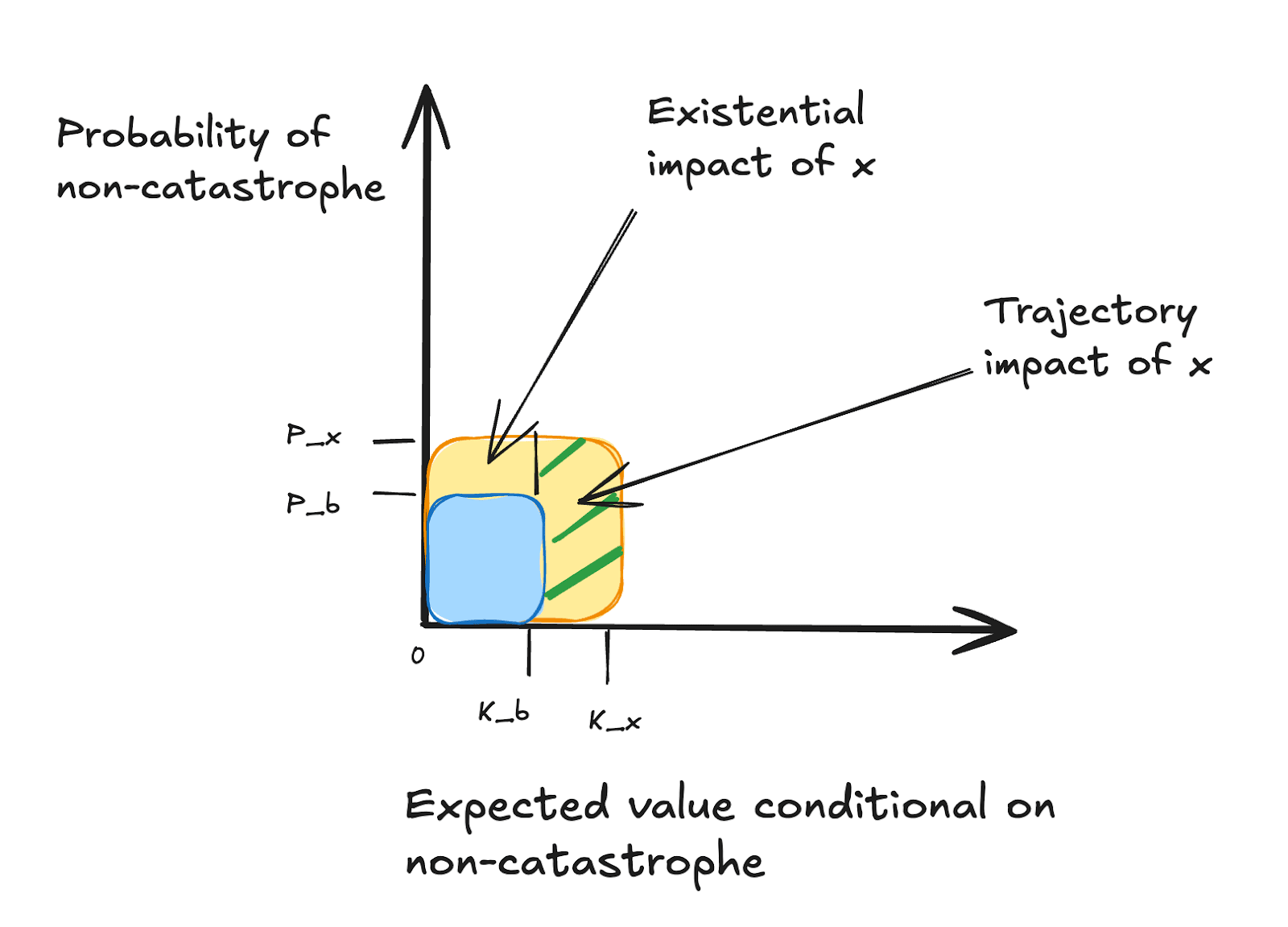

"An action x’s overall impact (ΔEVx) is its increase in expected value relative to baseline. We’ll let C refer to the state of existential catastrophe, and b refer to the baseline action. We’ll define, for any action x: Px=P[¬C | x] and Kx=E[V |¬C, x]. We can then break overall impact down as follows:

ΔEVx = (Px – Pb) Kb+ Px(Kx– Kb)

We call (Px – Pb) Kb the action’s existential impact and Px(Kx– Kb) the action’s trajectory impact. An action’s existential impact is the portion of its expected value (relative to baseline) that comes from changing the probability of existential catastrophe; an action’s trajectory impact is the portion of its expected value that comes from changing the value of the world conditional on no existential catastrophe occurring.

We can illustrate this graphically, where the areas in the graph represent overall expected value, relative to a scenario with a guarantee of catastrophe:

With these in hand, we can then define:

Maxipok (precisified): In the decision situations that are highest-stakes with respect to the longterm future, if an action is near‑best on overall impact, then it is close-to-near‑best on existential impact.

[1] Here’s the derivation. Given the law of total expectation:

To simplify things (in a way that doesn’t affect our overall argument, and bearing in mind that the “0” is arbitrary), we assume that E[V |C, x] = 0, for all x, so:

E[V|x] = P(¬C | x)E[V |¬C, x]

And, by our definition of the terms:

P(¬C | x)E[V |¬C, x] = PxKx

So:

ΔEVx= E[V|x] – E[V|b] = PxKx – PbKb

Then adding (PxKb – PxKb) to this and rearranging gives us:

One of the key issues with "making the future go well" interventions is that we start to run up against the reality that what is a desirable outcome for the future is so variable between different humans that the concept of making the future go well requires buying into ethical assumptions that people won't share, meaning that it's much less valid as any sort of absolute metric to coordinate around:

When people make statements that implicitly treat "the value of the future" as being well-defined, e.g. statements like “I define ‘strong utopia’ as: at least 95% of the future’s potential value is realized”, I’m concerned that these statements are less meaningful than they sound.

This level of variability is less for preventing bad outcomes, especially outcomes in which we don't die (though there is still variability here) because of instrumental convergence, and while there are moral views where dying/suffering isn't so bad, these moral views aren't held by many human beings (in part due to selection effects), so there's less of a chance to have conflict with other agents.

The other reason is humans mostly value the same scarce instrumental goods, but in a world where AI goes well, basically everything but status/identity becomes abundant, and this surfaces up the latent moral disagreements way more than our current world.

And yet, I think that very little AI safety work focuses on affecting P(things go really well | no AI takeover). Probably Forethought is doing the best work in this space.

Do you think this sort of work is related to AI safety? It seems to me that it's more about philosophy (etc.) so I'm wondering what you had in mind.

Yup! Copying over from a LessWrong comment I made:

Roughly speaking, I'm interested in interventions that cause the people making the most important decisions about how advanced AI is used once it's built to be smart, sane, and selfless. (Huh, that was some convenient alliteration.)

Smart: you need to be able to make really important judgment calls quickly. There will be a bunch of actors lobbying for all sorts of things, and you need to be smart enough to figure out what's most important.

Sane: smart is not enough. For example, I wouldn't trust Elon Musk with these decisions, because I think that he'd make rash decisions even though he's smart, and even if he had humanity's best interests at heart.

Selfless: even a smart and sane actor could curtail the future if they were selfish and opted to e.g. become world dictator.

And so I'm pretty keen on interventions that make it more likely that smart, sane, and selfless people are in a position to make the most important decisions. This includes things like:

Doing research to figure out the best way to govern advanced AI once it's developed, and then disseminating those ideas.

Helping to positively shape internal governance at the big AI companies (I don't have concrete suggestions in this bucket, but like, whatever led to Anthropic having a Long Term Benefit Trust, and whatever could have led to OpenAI's non-profit board having actual power to fire the CEO).

Helping to staff governments with competent people.

Helping elect smart, sane, and selfless people to elected positions in governments (see 1, 2).

Hmm, I think if we are in a world where the people in charge of the company that have already built ASI need to be smart/sane/selfless for things to go well, then we're already in a much worse situation than we should be, and things should have been done differently prior to this point.

I realize this is not a super coherent statement but I thought about it for a bit and I'm not sure how to express my thoughts more coherently so I'm just posting this comment as-is.

California state senator Scott Wiener, author of AI safety bills SB 1047 and SB 53, just announced that he is running for Congress! I'm very excited about this.

It’s an uncanny, weird coincidence that the two biggest legislative champions for AI safety in the entire country announced their bids for Congress just two days apart. But here we are.*

In my opinion, Scott Wiener has done really amazing work on AI safety. SB 1047 is my absolute favorite AI safety bill, and SB 53 is the best AI safety bill that has passed anywhere in the country. He's been a dedicated AI safety champion who has spent a huge amount of political capital in his efforts to make us safer from advanced AI.

On Monday, I made the case that donating to Alex Bores -- author of the New York RAISE Act -- calling it a "once in every couple of years opportunity", but flagging that I was also really excited about Scott Wiener.

I plan to have a more detailed analysis posted soon, but my bottom line is that donating to Wiener today is about 75% as good as donating to Bores was on Monday, and that this is also an excellent opportunity that will come up very rarely. (The main reason that it looks less good than donating to Bores is that he's running for Nancy Pelosi's seat, and Pelosi hasn't decided whether she'll retire. If not for that, the two donation opportunities would look almost exactly equally good, by my estimates.)

(I think that donating now looks better than waiting for Pelosi to decide whether to retire; if you feel skeptical of this claim, I'll have more soon.)

I have donated $7,000 (the legal maximum) and encourage others to as well. If you're interested in donating, here's a link.

Caveats:

If you haven't already donated to Bores, please read about the career implications of political donations before deciding to donate.

If you are currently working on federal policy, or think that you might be in the near future, you should consider whether it makes sense to wait to donate to Wiener until Pelosi announces retirement, because backing a challenger to a powerful incumbent may hurt your career.

*So, just to be clear, I think it's unlikely (20%?) that there will be a political donation opportunity at least this good in the next few months.

I feel pretty disappointed by some of the comments (e.g. this one) on Vasco Grilo's recent post arguing that some of GiveWell's grants are net harmful because of the meat eating problem. Reflecting on that disappointment, I want to articulate a moral principle I hold, which I'll call non-dogmatism. Non-dogmatism is essentially a weak form of scope sensitivity.[1]

Let's say that a moral decision process is dogmatic if it's completely insensitive to the numbers on either side of the trade-off. Non-dogmatism rejects dogmatic moral decision processes.

A central example of a dogmatic belief is: "Making a single human happy is more morally valuable than making any number of chickens happy." The corresponding moral decision process would be, given a choice to spend money on making a human happy or making chickens happy, spending the money on the human no matter what the number of chickens made happy is. Non-dogmatism rejects this decision-making process on the basis that it is dogmatic.

(Caveat: this seems fine for entities that are totally outside one's moral circle of concern. For instance, I'm intuitively fine with a decision-making process that spends money on making a human happy instead of spending money on making sure that a pile of rocks doesn't get trampled on, no matter the size of the pile of rocks. So maybe non-dogmatism says that so long as two entities are in your moral circle of concern -- so long as you assign nonzero weight to them -- there ought to exist numbers, at least in theory, for which either side of a moral trade-off could be better.)

And so when I see comments saying things like "I would axiomatically reject any moral weight on animals that implied saving kids from dying was net negative", I'm like... really? There's no empirical facts that could possibly cause the trade-off to go the other way?

Rejecting dogmatic beliefs requires more work. Rather than deciding that one side of a trade-off is better than the other no matter the underlying facts, you actually have to examine the facts and do the math. But, like, the real world is messy and complicated, and sometimes you just have to do the math if you want to figure out the right answer.

Per the Wikipedia article on scope neglect, scope sensitivity would mean actually doing multiplication: making 100 people happy is 100 times better than making 1 person happy. I'm not fully sold on scope sensitivity; I feel much more strongly about non-dogmatism, which means that the numbers have to at least enter the picture, even if not multiplicatively.

EDIT: Rereading, I'm not really disagreeing with you. I definitely agree with the sentiment here:

And so when I see comments saying things like "I would axiomatically reject any moral weight on animals that implied saving kids from dying was net negative", I'm like... really? There's no empirical facts that could possibly cause the trade-off to go the other way?

(Edited) So, rather than just the possibility that all tradeoffs between humans and chickens should favour humans, I take issue with >99% confidence in that position or otherwise treating it like it's true.

Whatever someone thinks makes humans infinitely more important than chickens[1] could actually be present in chickens in some similarly important form with non-tiny or even modest probability (examples here), or not actually be what makes humans important at all (more general related discussion, although that piece defends a disputed position). In my view, this should in principle warrant some tradeoffs favouring chickens.

Or, if they don't think there's anything at all, say except the mere fact of species membership, then this is just pure speciesism and seems arbitrary.

I also disagree with those comments, but can you provide more argument for your principle? If I understand correctly, you are suggesting the principle that X can be lexicographically[1] preferable to Y if and only if Y has zero value. But, conditional on saying X is lexicographically preferable to Y, isn't it better for the interests of Y to say that Y nevertheless has positive value? I mean, I don't like it when people say things like no amount of animal suffering, however enormous, outweighs any amount of human suffering, however tiny. But I think it is even worse to say that animal suffering doesn't matter at all, and there is no reason to alleviate it even if it could be alleviated at no cost to human welfare.

Maybe your reasoning is more like this: in practice, everything trades off against everything else. So, in practice, there is just no difference between saying "X is lexicographically preferable to Y but Y has positive value", and "Y has no value"?

From SEP: "A lexicographic preference relation gives absolute priority to one good over another. In the case of two-goods bundles, A≻B if a1>b1, or a1=b1 and a2>b2. Good 1 then cannot be traded off by any amount of good 2."

I think in practice most people have ethical frameworks where they have lexicographic preferences, regardless of whether they are happy making other decisions using a cardinal utility framework.

I suspect most animal welfare enthusiasts presented with the possibility of organising a bullfight wouldn't respond with "well how big is the audience?". I don't think their reluctance to determine whether bullfighting is ethical or not based on the value of estimated utility tradeoffs reflects either a rejection of the possibility of human welfare or a specieist bias against humans.

I like your framing though. Taken to its logical conclusion, you're implying:

(1) Some people have strong lexographic preferences for X over improved Y

(2) Insisting that the only valid ethical decision making framework is a mathematical total utilitarian one in which everything of value must be assigned cardinal weights implies that to maintain this preference they must reject the possibility of Y having value

(3) Acting within this framework implies they should also be indifferent to Y in all other circumstances, including when there is no tradeoff

(4) Demanding people with lexographic preferences for X shut up and multiply is likely to lead to lower total utility for Y. And more generally a world in which everyone acts as if any possibility they assign any value to may be multiplied and traded off against their own value sounds like a world in which most people will opt to care about as few possibilities as possible.

Amish Shah is a Democratic politician who's running for congress in Arizona. He appears to be a strong supporter of animal rights (see here).

He just won his primary election, and Cook Political Report rates the seat he's running for (AZ-01) as a tossup. My subjective probability that he wins the seat is 50% (Edit: now 30%). I want him to win primarily because of his positions on animal rights, and secondarily because I want Democrats to control the House of Representatives.

The page you linked is about candidates for the Arizona State House. Amish Shah is running for the U.S. House of Representatives. There are still campaign finance limits, though ($3,300 per election per candidate, where the primary and the general election count separately; see here).

People are underrating making the future go well conditioned on no AI takeover.

This deserves a full post, but for now a quick take: in my opinion, P(no AI takeover) = 75%, P(future goes extremely well | no AI takeover) = 20%, and most of the value of the future is in worlds where it goes extremely well (and comparatively little value comes from locking in a world that's good-but-not-great).

Under this view, an intervention is good insofar as it affects P(no AI takeover) * P(things go really well | no AI takeover). Suppose that a given intervention can change P(no AI takeover) and/or P(future goes extremely well | no AI takeover). Then the overall effect of the intervention is proportional to ΔP(no AI takeover) * P(things go really well | no AI takeover) + P(no AI takeover) * ΔP(things go really well | no AI takeover).

Plugging in my numbers, this gives us 0.2 * ΔP(no AI takeover) + 0.75 * ΔP(things go really well | no AI takeover).

And yet, I think that very little AI safety work focuses on affecting P(things go really well | no AI takeover). Probably Forethought is doing the best work in this space.

(And I don't think it's a tractability issue: I think affecting P(things go really well | no AI takeover) is pretty tractable!)

(Of course, if you think P(AI takeover) is 90%, that would probably be a crux.)

I, of course, agree!

One additional point, as I'm sure you know, is that potentially you can also affect P(things go really well | AI takeover). And actions to increase ΔP(things go really well | AI takeover) might be quite similar to actions that increase ΔP(things go really well | no AI takeover). If so, that's an additional argument for those actions compared to affecting ΔP(no AI takeover).

Re the formal breakdown, people sometimes miss the BF supplement here which goes into this in a bit more depth. And here's an excerpt from a forthcoming paper, "Beyond Existential Risk", in the context of more precisely defining the "Maxipok" principle. What it gives is very similar to your breakdown, and you might find some of the terms in here useful (apologies that some of the formatting is messed up):

"An action x’s overall impact (ΔEVx) is its increase in expected value relative to baseline. We’ll let C refer to the state of existential catastrophe, and b refer to the baseline action. We’ll define, for any action x: Px=P[¬C | x] and Kx=E[V |¬C, x]. We can then break overall impact down as follows:

ΔEVx = (Px – Pb) Kb+ Px(Kx– Kb)

We call (Px – Pb) Kb the action’s existential impact and Px(Kx– Kb) the action’s trajectory impact. An action’s existential impact is the portion of its expected value (relative to baseline) that comes from changing the probability of existential catastrophe; an action’s trajectory impact is the portion of its expected value that comes from changing the value of the world conditional on no existential catastrophe occurring.

We can illustrate this graphically, where the areas in the graph represent overall expected value, relative to a scenario with a guarantee of catastrophe:

With these in hand, we can then define:

Maxipok (precisified): In the decision situations that are highest-stakes with respect to the longterm future, if an action is near‑best on overall impact, then it is close-to-near‑best on existential impact.

[1] Here’s the derivation. Given the law of total expectation:

E[V|x] = P(¬C | x)E[V |¬C, x] + P(C | x)E[V |C, x]

To simplify things (in a way that doesn’t affect our overall argument, and bearing in mind that the “0” is arbitrary), we assume that E[V |C, x] = 0, for all x, so:

E[V|x] = P(¬C | x)E[V |¬C, x]

And, by our definition of the terms:

P(¬C | x)E[V |¬C, x] = PxKx

So:

ΔEVx= E[V|x] – E[V|b] = PxKx – PbKb

Then adding (PxKb – PxKb) to this and rearranging gives us:

ΔEVx = (Px–Pb)Kb + Px(Kx–Kb)"

What interventions are you most excited about? Why? What are they bottlenecked on?

One of the key issues with "making the future go well" interventions is that we start to run up against the reality that what is a desirable outcome for the future is so variable between different humans that the concept of making the future go well requires buying into ethical assumptions that people won't share, meaning that it's much less valid as any sort of absolute metric to coordinate around:

(A quote from Steven Byrnes here):

This level of variability is less for preventing bad outcomes, especially outcomes in which we don't die (though there is still variability here) because of instrumental convergence, and while there are moral views where dying/suffering isn't so bad, these moral views aren't held by many human beings (in part due to selection effects), so there's less of a chance to have conflict with other agents.

The other reason is humans mostly value the same scarce instrumental goods, but in a world where AI goes well, basically everything but status/identity becomes abundant, and this surfaces up the latent moral disagreements way more than our current world.

Do you think this sort of work is related to AI safety? It seems to me that it's more about philosophy (etc.) so I'm wondering what you had in mind.

Yup! Copying over from a LessWrong comment I made:

Roughly speaking, I'm interested in interventions that cause the people making the most important decisions about how advanced AI is used once it's built to be smart, sane, and selfless. (Huh, that was some convenient alliteration.)

And so I'm pretty keen on interventions that make it more likely that smart, sane, and selfless people are in a position to make the most important decisions. This includes things like:

Hmm, I think if we are in a world where the people in charge of the company that have already built ASI need to be smart/sane/selfless for things to go well, then we're already in a much worse situation than we should be, and things should have been done differently prior to this point.

I realize this is not a super coherent statement but I thought about it for a bit and I'm not sure how to express my thoughts more coherently so I'm just posting this comment as-is.

California state senator Scott Wiener, author of AI safety bills SB 1047 and SB 53, just announced that he is running for Congress! I'm very excited about this.

It’s an uncanny, weird coincidence that the two biggest legislative champions for AI safety in the entire country announced their bids for Congress just two days apart. But here we are.*

In my opinion, Scott Wiener has done really amazing work on AI safety. SB 1047 is my absolute favorite AI safety bill, and SB 53 is the best AI safety bill that has passed anywhere in the country. He's been a dedicated AI safety champion who has spent a huge amount of political capital in his efforts to make us safer from advanced AI.

On Monday, I made the case that donating to Alex Bores -- author of the New York RAISE Act -- calling it a "once in every couple of years opportunity", but flagging that I was also really excited about Scott Wiener.

I plan to have a more detailed analysis posted soon, but my bottom line is that donating to Wiener today is about 75% as good as donating to Bores was on Monday, and that this is also an excellent opportunity that will come up very rarely. (The main reason that it looks less good than donating to Bores is that he's running for Nancy Pelosi's seat, and Pelosi hasn't decided whether she'll retire. If not for that, the two donation opportunities would look almost exactly equally good, by my estimates.)

(I think that donating now looks better than waiting for Pelosi to decide whether to retire; if you feel skeptical of this claim, I'll have more soon.)

I have donated $7,000 (the legal maximum) and encourage others to as well. If you're interested in donating, here's a link.

Caveats:

*So, just to be clear, I think it's unlikely (20%?) that there will be a political donation opportunity at least this good in the next few months.

I feel pretty disappointed by some of the comments (e.g. this one) on Vasco Grilo's recent post arguing that some of GiveWell's grants are net harmful because of the meat eating problem. Reflecting on that disappointment, I want to articulate a moral principle I hold, which I'll call non-dogmatism. Non-dogmatism is essentially a weak form of scope sensitivity.[1]

Let's say that a moral decision process is dogmatic if it's completely insensitive to the numbers on either side of the trade-off. Non-dogmatism rejects dogmatic moral decision processes.

A central example of a dogmatic belief is: "Making a single human happy is more morally valuable than making any number of chickens happy." The corresponding moral decision process would be, given a choice to spend money on making a human happy or making chickens happy, spending the money on the human no matter what the number of chickens made happy is. Non-dogmatism rejects this decision-making process on the basis that it is dogmatic.

(Caveat: this seems fine for entities that are totally outside one's moral circle of concern. For instance, I'm intuitively fine with a decision-making process that spends money on making a human happy instead of spending money on making sure that a pile of rocks doesn't get trampled on, no matter the size of the pile of rocks. So maybe non-dogmatism says that so long as two entities are in your moral circle of concern -- so long as you assign nonzero weight to them -- there ought to exist numbers, at least in theory, for which either side of a moral trade-off could be better.)

And so when I see comments saying things like "I would axiomatically reject any moral weight on animals that implied saving kids from dying was net negative", I'm like... really? There's no empirical facts that could possibly cause the trade-off to go the other way?

Rejecting dogmatic beliefs requires more work. Rather than deciding that one side of a trade-off is better than the other no matter the underlying facts, you actually have to examine the facts and do the math. But, like, the real world is messy and complicated, and sometimes you just have to do the math if you want to figure out the right answer.

Per the Wikipedia article on scope neglect, scope sensitivity would mean actually doing multiplication: making 100 people happy is 100 times better than making 1 person happy. I'm not fully sold on scope sensitivity; I feel much more strongly about non-dogmatism, which means that the numbers have to at least enter the picture, even if not multiplicatively.

EDIT: Rereading, I'm not really disagreeing with you. I definitely agree with the sentiment here:

(Edited) So, rather than just the possibility that all tradeoffs between humans and chickens should favour humans, I take issue with >99% confidence in that position or otherwise treating it like it's true.

Whatever someone thinks makes humans infinitely more important than chickens[1] could actually be present in chickens in some similarly important form with non-tiny or even modest probability (examples here), or not actually be what makes humans important at all (more general related discussion, although that piece defends a disputed position). In my view, this should in principle warrant some tradeoffs favouring chickens.

Or, if they don't think there's anything at all, say except the mere fact of species membership, then this is just pure speciesism and seems arbitrary.

Or makes humans matter at all, but chickens lack, so chickens don't matter at all.

I also disagree with those comments, but can you provide more argument for your principle? If I understand correctly, you are suggesting the principle that X can be lexicographically[1] preferable to Y if and only if Y has zero value. But, conditional on saying X is lexicographically preferable to Y, isn't it better for the interests of Y to say that Y nevertheless has positive value? I mean, I don't like it when people say things like no amount of animal suffering, however enormous, outweighs any amount of human suffering, however tiny. But I think it is even worse to say that animal suffering doesn't matter at all, and there is no reason to alleviate it even if it could be alleviated at no cost to human welfare.

Maybe your reasoning is more like this: in practice, everything trades off against everything else. So, in practice, there is just no difference between saying "X is lexicographically preferable to Y but Y has positive value", and "Y has no value"?

From SEP: "A lexicographic preference relation gives absolute priority to one good over another. In the case of two-goods bundles, A≻B if a1>b1, or a1=b1 and a2>b2. Good 1 then cannot be traded off by any amount of good 2."

I think in practice most people have ethical frameworks where they have lexicographic preferences, regardless of whether they are happy making other decisions using a cardinal utility framework.

I suspect most animal welfare enthusiasts presented with the possibility of organising a bullfight wouldn't respond with "well how big is the audience?". I don't think their reluctance to determine whether bullfighting is ethical or not based on the value of estimated utility tradeoffs reflects either a rejection of the possibility of human welfare or a specieist bias against humans.

I like your framing though. Taken to its logical conclusion, you're implying:

(1) Some people have strong lexographic preferences for X over improved Y

(2) Insisting that the only valid ethical decision making framework is a mathematical total utilitarian one in which everything of value must be assigned cardinal weights implies that to maintain this preference they must reject the possibility of Y having value

(3) Acting within this framework implies they should also be indifferent to Y in all other circumstances, including when there is no tradeoff

(4) Demanding people with lexographic preferences for X shut up and multiply is likely to lead to lower total utility for Y. And more generally a world in which everyone acts as if any possibility they assign any value to may be multiplied and traded off against their own value sounds like a world in which most people will opt to care about as few possibilities as possible.

This page could be a useful pointer?

Amish Shah is a Democratic politician who's running for congress in Arizona. He appears to be a strong supporter of animal rights (see here).

He just won his primary election, and Cook Political Report rates the seat he's running for (AZ-01) as a tossup. My subjective probability that he wins the seat is 50% (Edit: now 30%). I want him to win primarily because of his positions on animal rights, and secondarily because I want Democrats to control the House of Representatives.

You can donate to him here.

Applicable campaign finance limits: According to this page, individuals can donate up to $5,400 to legislative candidates per two-year election cycle.

The page you linked is about candidates for the Arizona State House. Amish Shah is running for the U.S. House of Representatives. There are still campaign finance limits, though ($3,300 per election per candidate, where the primary and the general election count separately; see here).