Vasco Grilo🔸

Bio

Participation4

I am a generalist quantitative researcher. I am open to volunteering and paid work. I welcome suggestions for posts. You can give me feedback here (anonymously or not).

How others can help me

I am open to volunteering and paid work (I usually ask for 20 $/h). I welcome suggestions for posts. You can give me feedback here (anonymously or not).

How I can help others

I can help with career advice, prioritisation, and quantitative analyses.

Posts 217

Comments2689

Topic contributions37

Great post, Jakub and Weronika!

- Anima International became increasingly worried that any effort to displace carp consumption may lead to increased animal suffering due to salmon farming requiring fish feed.

One could argue banning live carp sales is good due to improving attitudes towards animals, even if it may decrease the welfare of farmed animals. I think the case for chicken welfare reforms increasing animal welfare accounting for effects on non-target beneficiaries is also very uncertain. I estimate the effects on soil animals are much larger than those on chickens, and I have very little idea about whether the effects on soil animals are positive or negative. It might still make sense to prioritise banning live carp sales less relative to chicken welfare reforms if one is concerned about effects on non-target beneficiaries, and increasing animal welfare robustly. However, in this case, I think it makes much more sense to prioritise chicken welfare reforms less (at the margin) relative to understanding effects on soil animals, and decreasing uncertainty about interspecies welfare comparisons.

Overal I think more people who have insights on cause prio should be saying: if I had a billion dollars, here's how I'd spend it, and why.

I see some value in this. However, I would be much more interested in how they would decrease the uncertainty about cause prioritisation, which is super large. I would spend at least 1 %, 10 M$ (= 0.01*1*10^9), decreasing the uncertainty about comparisons of expected hedonistic welfare across species and substrates (biological or not). Relatedly, RP has a research agenda about interspecies welfare comparisons more broadly (not just under expectational total hedonistic utilitarianism).

Our best-guess estimate of GWWC’s giving multiplier for 2023–2024 was 6x, implying that for the average $1 we spent on our operations, we caused $6 of value to go to highly effective charities or funds.

Animal Charity Evaluators (ACE) estimated a giving multipler for their charity evaluations from April 2024 to March 2025 of 6.05, which is very similar to the above.

I think it would be helpful to include the annual spending of the charities in this or similar future posts. This would give a better picture of their cost-effectiveness than their recent achievements alone.

Relatedly, in your post about influenced giving reports, you mention how much funding you counterfactuall influenced, but I believe it would also be good to mention your estimates for the giving multiplier (the funding your counterfactually influenced as a fraction of your spending).

Thanks for the good points, Jason.

Would you assign value to the indirect protective effect on those you live with (if any), friends, and family members?

Yes. However, I estimate I would have to infect more than 1.60 k people conditional on getting a symptomatic flu for the health benefits to other people to exceed the impact of donating 24.7 $ to the most cost-effective global health interventions, which is the difference between my estimates for the cost and benefits. I would also limit my contact to a few people I live with if I had a symptomatic flu.

Maybe you could consider willingness to pay for pleasurable leisure activities, and then decide how many of those activities you'd be willing to forego to avoid enduring one average case of the flu?

I think my willingness to pay for extra working and leisure time should be the same. Otherwise, I should spend more/less time on what I think is the most/least valuable per hour at the margin until my willingness to pay for extra working and leisure time is the same.

- 1.5 hr is a lot to get a flu vaccine by US standards; they are available on a walk-in basis at pharmacies everywhere. That's not a critique of your analysis, of course.

- Could you call ahead and ensure that where you were going to get the vaccine used Influvac or Vaxigrip? (I assume fewer places would stock Fluenz, anyway due to cost.)

Interesting. In Portugal, people like me who are not covered by free vaccination need to get a doctor's prescription.

For people not covered by free vaccination, the flu vaccine is dispensed at community pharmacies with a doctor's prescription and subject to stock availability.

I also assume I would have to book it in advance to ensure there is enough stock, and because people who are covered by free vacination also have to book it. My time cost of 1.5 h is supposed to account not only for the time to get the vaccine, but also booking it, getting a doctor's prescription, and understanding whether this is even feasible in the 1st place (considering I am a healthy young adult).

- For most people, the hours of their day do not have equal value or utility. I can't -- at least not on a regular basis -- realistically use the 14th most valuable hour of my day for renumerative work, but I could use it to get a vaccine. In other words, there's a limit on how many hours I can sustain higher-demand activities. In contrast, when I get the flu, I think the loss in productivity hits the relevant time slots more evenly.

Nice point. I should clarify I am considering as productive all the activities I log in my time sheet, not just my main activity of paid work. Ideally, the marginal hour spent on each activity would be the same. In any case, I agree there are times in the day that are less productive. I would prefer to get a vaccine late in the afternoon just before dinner than in the middle of the morning or afternoon.

I don't know if those adjustments would flip the end result for you -- but I think accounting for them would make it a close call and would show how modest differences in the factors (e.g., personal circumstances that make getting the vaccine less time-consuming) would flip the outcome.

Yes, I can see vaccination being worth it for young healthy under some conditions. Thanks for bringing attention to this.

Hi Nick. Fair point. I thought about those effects, but should have explained why I did not cover them in the post. I have now added the following to the summary and main text.

I have not considered the effects of my vaccination on other people, soil animals, or microorganisms, but they do not change my decision. I think they are much smaller than the effects on my work and donations resulting from the time and monetary costs of my vaccination.

My marginal earnings go towards donations, and I believe donating the difference between my estimates for the cost and benefits of 24.7 $ to the most cost-effective global health interventions would increase human welfare more than the benefits of my vaccination to other people. GiveWell published a report on dietary salt modification in July 2025 where they concluded the following.

Overall, we estimate that it costs about $855 to avert a death via dietary salt modification in China and India, and the intervention is about 14 times as cost-effective as spending on unconditional cash transfers. However, this is a preliminary estimate that we plan to refine with additional work.

According to Coefficient Giving (CG), “GiveWell uses moral weights for child deaths that would be consistent with assuming 51 years of foregone life in the DALY framework (though that is not how they reach the conclusion)”. Assuming 51 DALY/life, the above cost-effectiveness would be 0.0596 DALY/$ (= 51/855). So 24.7 $ would avert 1.47 DALYs (= 24.7*0.0596). Supposing 1 DALY/symptomatic-flu-year, which greatly overestimate the badness of having a symptomatic flu, my vaccination would only be worth it if it averted more than 1.47 symptomatic-flu-years (= 1.47/1) in other people, or 97.6 symptomatic flus (= 1.47/(5.50/365.25)) for my assumption of 5.50 days of symptoms per symptomatic flu.

The benefits to other people would only materialise in cases where the vaccination prevented me from getting a symptomatic flu, which is when I could have infected other people. Combining the above with my assumption of "0.0610 symptomatic flus per person-year", I estimate I would have to have infected 1.60 k (= 97.6/0.0610) people conditional on getting a symptomatic flu for my vaccination to be worth it. In contrast, I would only contact with a few people if I had a symptomatic flu.

I believe I should consider effects not only on other people, but also on all potential beings. I suspect effects on soil animals and microorganisms are the driver of the overall effect, and I have very little idea whether their welfare would be increased or decreased. In any case, I think the conclusion accounting for all beings would still be that I should optimise for increasing the impact from my work and donations, which points towards my vaccination not being worth it.

Thanks for the follow-up, Whitney! I strongly upvoted it.

RE: The number of broiler chickens raised in China annually:

I have shared the estimates you provided with one person from the FAO.

https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/sjjd/202501/t20250117_1958344.html/

Nitpick. "/" at the end has to be removed for the link to work.

6.5 billion egg-laying hens are in cages each year globally

This implies 23.0 % (= 1 - 6.5*10^9/(8.44*10^9)) of all laying hens outside cages assuming 8.44 billion laying hens as reported by FAO. I believe this fraction is too high. How did you get the 6.5 billion laying hens in cages globally? Do you think there are more than 8.44 billion laying hens globally?

any way you cut it it [broilers in cages] is a very major problem

Makes sense!

Thanks for the update, Nuno and Rai! I read the summary of weekly brief every week.

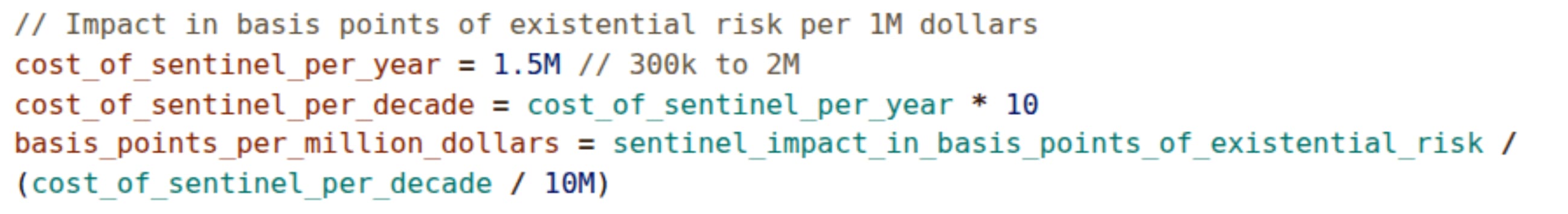

The last 10 M should be 1 M?

Thanks for comment, Elijah!

I did not find a free version of Elizabeth's article Developing Valid Behavioral Indicators of Animal Pain, but I have now read this summary from Gemini, and this related article by Elizabeth. I agree with her that nociception does not necessarily imply sentience, but I do not rule this out. Here are some paragraphs I like from the article “All animals are conscious”: Shifting the null hypothesis in consciousness science by Kristin Andrews which relate to the article from Elizabeth you shared.

I skimmed the article Disentangling perceptual awareness from nonconscious processing in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) by Moshe Ben-Haim and others. I liked it, but I believe Kristin's criticism of defining markers of consciousness applies all the same.

I would like the focus to be on comparisons of expected hedonistic welfare across species and substrates (biological or not) instead of their probabilty of sentience. Relatedly, Rethink Priorities (RP) has a research agenda about interspecies welfare comparisons more broadly (not just under expectational total hedonistic utilitarianism).