Abstract

The Essays on Longtermism extensively discuss the risks of epistemic uncertainty, but I argue that a deeper risk is ontological misalignment: being wrong about what exists and therefore about what matters. Using a simple vector model, , I show that the expected value of action depends multiplicatively on directional alignment with moral truth. Historical precedent and plausible future discoveries suggest that our current misalignment angle, Θ, is large, making discovery itself a dominant source of value. I propose Ontological Longtermism, the view that improving our ontologies is a central longtermist aim. This entails explicitly modeling Θ, investing in discovery and meta-epistemic infrastructures to reduce it, and establishing safeguards against ontological lock-in. On this view, longtermism becomes a project of discovery before optimization.

1. Flawed ontologies, flawed decisions

Recent scientific history is punctuated by revelations about what exists: germs, evolution, deep time, the Big Bang. If longtermism aims to shape the far future, it must take seriously the possibility of equally radical breakthroughs ahead.

Greaves and McCaskill gesture at the importance of poor ontologies:

“would-be longtermists in the Middle Ages…might instead have backed attempts to spread Christianity, perhaps by violence: a putative route to value that, by our more enlightened lights today, looks wildly off the mark.”

Yet they conclude that “these issues need not occasion any deep structural change to the analysis,” treating the problem as merely one of ex ante decision-making.

But this framing sidesteps the deeper danger.

Why were those medieval would-be longtermists “wildly off the mark”? Because despite reasonable ex ante choices, their ontologies were flawed. They had mistaken ideas about what exists and, consequently, what matters.

If our predecessors in the not-too-distant past were led astray by false ontologies, the same risk applies to us.

The limits of ex ante reasoning

This all makes ex ante rationality suspect. It works in games like poker—where ontologies of cards, rules, values, and probabilities are fixed and known. But our epistemic situation is different: our ontologies are uncertain, and it is likely that new ones will be discovered.

Ontologies are crucial considerations, and mistaken ones can send us down disastrously misguided paths. To see this, let’s use Bostrom’s compass analogy in his essay on crucial considerations: we may try to reach some destination using a compass, but we can’t be sure the compass is accurate. Longtermists, likewise, attempt to navigate toward high value. But since we can’t be sure where north is, our calculations could be very wrong.

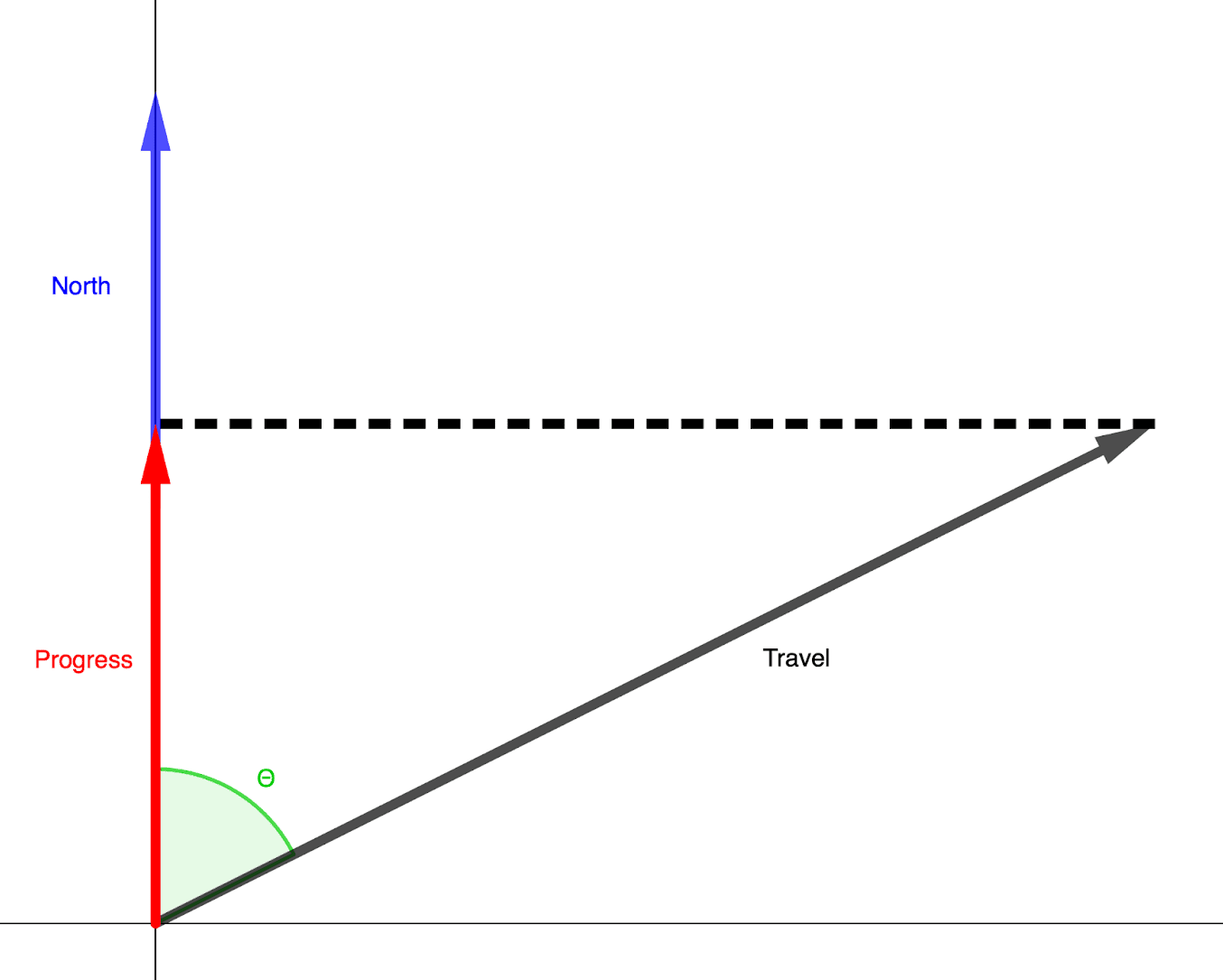

Instead of thinking of value as a scalar, we might see it as a vector. If we want to go north, then our progress northward depends on how our travel vector aligns with the unit True North vector :

Notice that our progress northward is proportional to distance traveled () and our angular alignment with True North (). If our compass is far off, we may even walk confidently in the wrong direction, making negative progress.

Ordinary ex ante reasoning ignores this vector. It assumes we are doing the best we can to move toward Moral North, treating uncertainty as additive when it may be multiplicative: our apparent progress can be scaled—even reversed—by how correct our ontology is. This oversight lets us bracket off ignorance instead of confronting it, potentially locking in blind spots and false values simply because we fail to assign appropriate priority to discovery.

Ontological Longtermism: From ex ante to ex obscura

I propose that we should not be reasoning ex ante (“before the event”) but ex obscura (“from the unknown”). Whereas ex ante reasoning lets us off the hook for what we don’t know, ex obscura emphasizes those unknowns and implores us to reduce our ignorance.

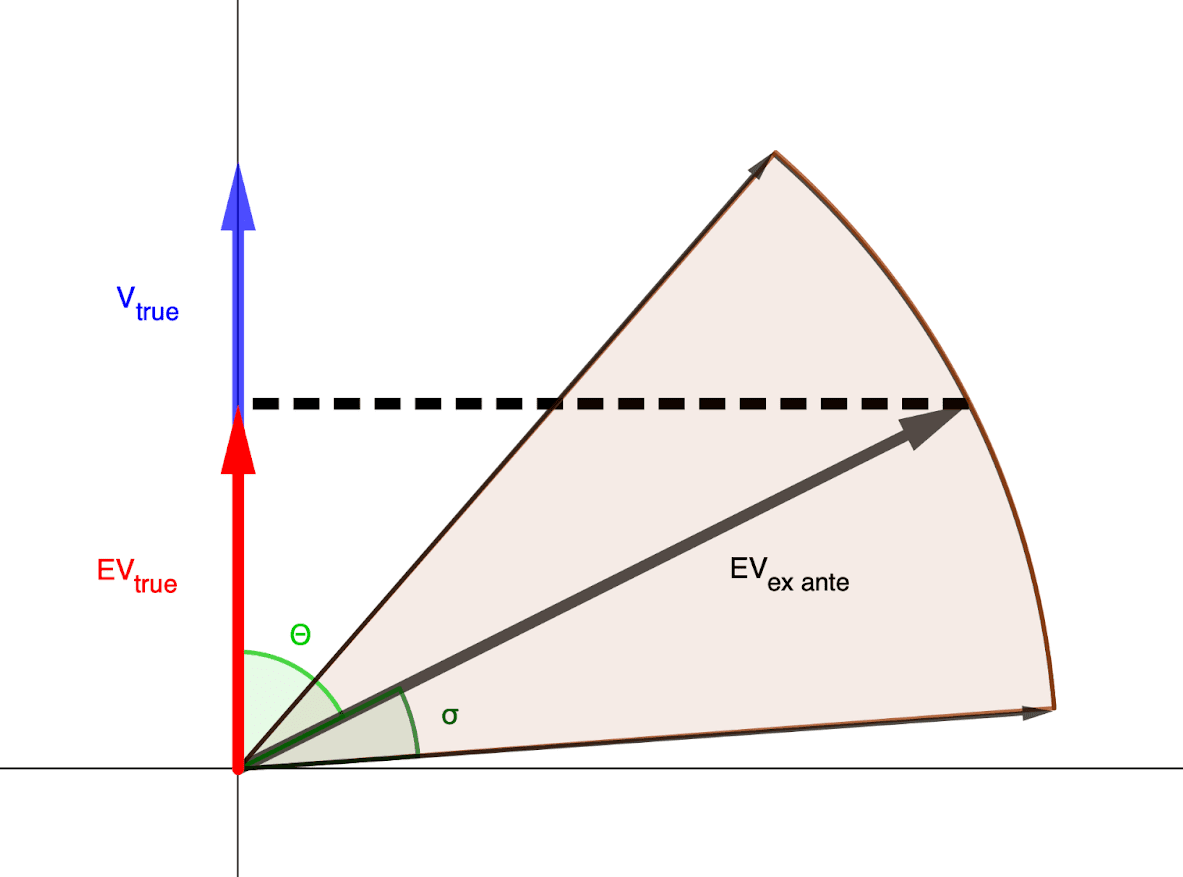

To make this explicit, we can write

Here Θ is the misalignment between our moral ontology and Moral North. Ex ante decisions only align with real moral value when ontologies are accurate. And since our ontologies have recently undergone rapid change, we should expect significant updates in the future. This is especially important in the far future, where even a small Θ can lead to huge errors.

These considerations motivate what I call Ontological Longtermism: the view that improving our ontology is itself a high-priority goal for any far-future-facing agent. In brief, longtermists should (i) account for relevant ontologies and their uncertainty, (ii) recognize that future moral reasoning will emerge from currently unknown ontologies, and (iii) assign appropriate weight to ontological improvement itself.

The next section explores some theoretical implications. Part 2 will explain my reasoning that Θ is large. Then Part 3 will lay out how to put Ontological Longtermism into practice.

Decision-making with ontological uncertainty

When we acknowledge that our ex obscura situation—i.e. that our ex ante moral directions may be based on flawed ontologies—we can begin to model interventions intended to reduce our ignorance.

Marginal value of discovery

Recall the equation above for true expected value, EVtrue. To calculate marginal value of discovery, we differentiate with respect to discovery D:

which is positive whenever discovery reduces misalignment ( < 0).

In short, the true marginal value of discovery depends on how rapidly discovery realigns our moral compass: gains are larger when misalignment is wide or easily corrected.

Because discovery can change direction as well as magnitude, it scales with our ex-ante capacity for impact: the larger our civilization’s reach and the longer our timeline, the more crucial even small ontological corrections become.

Ontological uncertainty vs epistemic uncertainty

Many chapters of Essays on Longtermism treat uncertainty as epistemic—about the precision of our estimates or our ability to instrumentally reach chosen targets—rather than about the correctness of our underlying ontology. This uncertainty can be modeled as a cone around our vector with dispersion factor σ:

This geometric framing lets us compare meta-intervention types directly. We can even add a cone around to represent ontological uncertainty and calculate overlaps. We can then estimate the relative marginal investment values between the different meta-tasks of epistemic uncertainty reduction, ontological uncertainty reduction, and ontological discovery. I leave formal derivations for future work.

For present purposes, the image yields a simple heuristic: Reducing Θ (improving ontologies) dominates reducing σ (refining precision) when Θ is large. And given our historical track record and vast remaining ignorance, Θ is almost certainly large. We will examine this claim in Part 2.

Dimensionality and complexity

To be clear, I’m not trying to argue that value-space is two-dimensional in this simplistic way. I’m trying to show the importance of ontology using a simple 2D model. True value-space is likely high-dimensional, involving geometries with much more complexity.

In this case, we may be almost completely clueless, which we can model by randomizing the direction of . For a high-dimensional space, it’s probable that a randomized is nearly orthogonal to —especially when yet-undiscovered ontologies are involved—further emphasizing the need for improving our ontologies.

And if true value-space ends up being more complex than this model, ontological discovery gains even more importance.

2. How big is Θ?

We have strong reason to believe our current ontological misalignment Θ is large. Examples from history, emerging developments, and plausible far-future discoveries all suggest that the true structure of value may drastically differ from what we now assume.

Historical evidence

A prominent example of a flawed ontology is the one discussed by Greaves and McCaskill: would-be effective altruists in the Middle Ages. Those well-meaning people would likely have attempted to spread Christianity: saved eternal souls are infinitely valuable. Unfortunately, souls are not ontologically real, so those well-meaning, ex ante reasonable efforts pushed the world in suboptimal—possibly even negative—directions.

Germ theory is a more subtle example. Its discovery primarily reduced σ by improving tractability in public health, but it also slightly corrected Θ by replacing moralized or theistic models of disease with mechanistic ones.

Moral circle expansion in recent centuries has extended our ethical concern to women, LGBTQ, animals, and spatiotemporally distant entities. Where will such revisions end?

Longtermism itself is highly dependent on our cosmic ontology, which has undergone significant recent revision. In the 1940s, we discovered that the Earth will become uninhabitable in ~109 years. Exoplanets were first confirmed in 1992. Only in 1998 did we learn that universal expansion was accelerating. These ontological features of reality alter our future projections and moral decision-making.

History shows us in retrospect that Θ was large.

Near-future ontologies

In addition to historical evidence for deep ontological skew, we have plausible new ontologies in our near future. Some of these will be uncovered through direct research, and others by emergent technologies and cultures, possibly within the next thousand years.

Near-future discoveries

Cosmology and fundamental physics offer many promising directions for new ontologies. Quantum gravity is an active source of research that could unite quantum mechanics and general relativity. Primordial gravitational waves from the Big Bang could give tantalizing clues about the origin of the universe and spawn new research directions. Dark matter and dark energy both lay just beyond our understanding. Bigger particle accelerators will probe the fundamental forces of reality and spacetime. The James Webb Space Telescope and its successors will reveal untold features of the universe. Any new discoveries here can significantly reshape our understanding of what is possible and ideal.

Consciousness studies are relatively new and undeveloped, but they can have profound impacts on our moral reasoning, especially for ethical frameworks that place large emphasis on pleasure and suffering. Live biologies are notoriously difficult to study scientifically and ethically, yet we can already create rudimentary brain-computer interfaces, which improve every year. It may soon be possible to compare the sentient suffering of shrimp and humans, allowing us to make more precise moral calculations.

The potential discovery of alien life is difficult to predict, but it would immediately change our sense of the future of humanity. Planned missions to planets and moons in our solar system could discover primitive life within the next twenty years, drastically altering our estimates of life in the universe. An alien transmission or visitor could be received any day, revealing humanity to be part of a cosmic community, rather than a lone intelligent species.

Near-future emergence

New morally significant ontologies are also likely to emerge through technological and societal developments. Though it’s difficult to accurately predict their effects, these examples may change our understanding of moral values.

Long-lived humans—those living hundreds of years or more—would drastically alter the shape of society. Acquired expertise would accrue greater benefit, even as new challenges arise. Institutions would require significant change, and ideas about the good life would rapidly adjust.

We have already seen the conglomeration of humans into increasingly large human structures: tribes have gathered into states, nations, and an interconnected global civilization. These are real ontologies which require separate moral considerations than their constituent parts. Interplanetary and intergalactic space flight may soon birth huge human structures. As humanity expands and changes the nature of its interconnectedness, so too will our definitions and moral understandings.

With growing personal connections to technology, cyborgs are on the horizon. We began this process long ago, e.g. writing allowed us to offload memory tasks to external technology. This process is ongoing, and our minds are now distributed with wearable devices and phones constantly within reach. It’s likely we will permanently augment ourselves with devices to increase our mental capacities and interconnectivity. Future cyborgs may have dramatically different experiences of life, and therefore we will need to reconsider their moral valuations.

Sentient AI is already on many longtermist radars. Any sentience we create will immediately deserve moral consideration in ethical views that prioritize conscious experience. Accounting for these newly created beings will necessitate significant changes to moral calculus.

All of these novel near-future ontologies show that Θ is still large.

Far-future ontologies

Far-future ontologies will go even further and challenge our basic understanding of the world. We likely can’t even imagine what will emerge, nor what they will mean for ethics.

These new ontologies may not be just the infinite values of Tarsney and Wilkinson, but entirely new categories of moral importance. In the same way that reasoning about the value of souls was misguided, we may find that the value of lives, or QALYs, or conscious experience is also misguided. We may find that values aren’t as cleanly additive as we model them, or that truer models of ethics are as counterintuitive as quantum physics.

Here are just a few possible far-future ontological discoveries that would completely alter our ideas of goodness.

- Simulations and theologies have been much discussed recently and through history, and it’s clear that such ontologies would have drastic moral implications.

- Finding that we are part of a large multiverse structure might reveal the moral importance of producing a specific object, like a skin cell who learns it must produce keratin for the survival of the larger body.

- Smolin’s ‘cosmological natural selection’ hypothesis, if true, would imply an additional source of good: discovering how to affect moral events beyond our own local cosmos. This could include now-or-never interventions, like gathering mass-energy before galaxies spread too thinly.

These are admittedly speculative, but so is the assumption that no other pertinent ontologies exist. Such assumptions are irresponsible extrapolations into a vast unknown parameter space, given that our n=1 for observations of universes.

We are therefore in nearly complete uncertainty about the larger cosmos, and all of our credences are founded on unsettled ground. We could be rowing in entirely wrong directions, a risk that only grows the longer we row. Over long horizons, tail ontologies will dominate if we aren’t humble about our ontologies and don’t pursue enough discovery.

Ontological humility

A large Θ means we need to build ontological humility into our long-term ethical projects. In the same way that epistemic humility implores us to use wide error bars (large σ) and improve models within a given worldview, ontological humility reminds us that the worldview itself may be incomplete or misaligned. It implies:

- a deep uncertainty about moral frameworks: both a large Θ, and a wide cone of uncertainty around our estimate of Moral North;

- the need to better understand reality through investments in discovery.

By emphasizing ontological humility, we become cautious about overconfidently barreling down moral pathways. Rather than trying to cover all of our ex ante bases with ever-wider error bars or ‘catchall’ states, we acknowledge our ex obscura condition. With this additional form of humility, we can avoid deep value lock-in, lest we devote vast resources to saving non-existent souls.

Acknowledging the persistence of ontological misalignment, we must now ask how to act responsibly within it.

3. Implementing Ontological Longtermism

Once we acknowledge the need for ontological improvement, we need to consider the best way to do so. Let’s discuss practical considerations.

Estimating Θ and allocating investments

While the formal relationship between investment and uncertainty can be derived from the geometric models above, the main question is how to estimate Θ, the degree of our ontological misalignment. Historical precedent gives us reason to suspect substantial misalignment, but how much?

At present, we lack any reasonable bounds on Θ. Developing methods to constrain this range should therefore be a priority in its own right. It would allow us to translate ontological humility into quantitative guidance for longtermist investment. These estimates are beyond the scope of this essay (and the capabilities of this writer).

Until such bounds are known, the ontologically humble approach is to assume Θ is large and to act as if substantial ontological correction lies ahead. Large sources of value—like existential risk mitigation—probably still dominate, but ontological discovery may take priority over smaller meta-gains in epistemic uncertainty σ.

Types of ontological improvement investments

Here are some investments which have high potential for Θ reduction.

Since the nature of reality and our experience of it are so important for our understanding of morality, foundational science fields—cosmology, physics, consciousness studies—are natural priorities. While these fields already advance for independent scientific reasons, Ontological Longtermism would elevate their moral significance: progress directly reduces Θ. Even if financially demanding, such work may yield disproportionate moral returns.

Beyond empirical discovery, foundational philosophical work in metaethics also deserves special emphasis. Questions about moral realism, the structure of moral truth, and the ontological status of value itself bear directly on Θ. While empirical discovery can reveal what exists, metaethics probes what matters within those existents: whether value supervenes on consciousness, relations, complexity, or something deeper. Supporting metaethical research, especially in dialogue with cognitive science and metaphysics, can therefore produce high-leverage reductions in Θ at low material cost. Clarifying these foundations can sharply realign our moral compass, even before new empirical discoveries arrive.

It’s possible that our empirical measurements of the universe are sufficient for constructing nearly correct ontologies, yet our institutions suffer from ontological lock-in—structural inertia that prevents us from reinterpreting data in new ontological frames. Developing meta-epistemic infrastructures could help audit and revise those frames. Such efforts might include greater support for philosophy of science, institutionalizing ontological diversity among research programs, and fostering cross-disciplinary translation efforts to extract more ontological insight from existing empirical knowledge.

The Essays on Longtermism frequently discuss ways to avoid value lock-in, but since values are downstream of ontologies, we also need to create safeguards against ontological lock-in. Such safeguards might include designing corrigible institutions and AI, replete with meta-epistemic infrastructures. Since meta-epistemology is also cultural, we should also include ontological humility and awareness as part of civic education.

What if we don’t discover anything?

Since new ontologies are highly speculative, it’s possible that there are no more significant ones to discover. If we search and come up empty, would this make Ontological Longtermism a failed idea?

No. Even if the possible side benefits listed above—improved understandings and avoidance of lock-in—don’t materialize, Ontological Longtermism would not have been a waste. If we are properly accounting for our ex obscura context, then we are using ex ante reasoning well: doing the best we can with our ignorance. We need not feel shame for making positive EV poker plays that don’t go our way, and we need not despair that ontological discovery efforts are wasteful if they come up empty.

4. Conclusion

Longtermism’s familiar remedy for uncertainty is to widen error bars and improve estimates. That is prudent, but it assumes the space of moral relevance is already right. History shows that assumption is unsafe. The vector model makes the asymmetry vivid: our realized impact depends on how well our direction aligns with True North. When Θ is large, meticulous optimization can drive negative progress.

Ontological Longtermism is the corrective. It reframes the project as discovery before optimization. Practically, this means three commitments:

- Model Θ explicitly. Treat ontological misalignment as a first-class uncertainty, distinct from epistemic variance σ. When they trade off, large Θ dominates σ.

- Invest to reduce Θ. Prioritize discovery in domains that can reconfigure the moral landscape (foundational physics and cosmology, consciousness science and comparative sentience, the search for life), and build meta-epistemic infrastructures: institutions that continuously audit, translate, and revise ontological frames—so we don’t build precision inside the wrong worldview.

- Prevent lock-in. Safeguard against ontological as well as value lock-in in governance and AI design (corrigibility, diversity of research programs, civic education in ontological humility).

Even if discovery yields few surprises, the costs are insurance premiums against civilization-scale wrong-way risk; the benefits include clearer bounds on Θ and a stronger warrant for confident optimization.

Our choice, then, is not between mere discovery and doing good. It is between discovering what good is and optimizing inside a potentially fictive map. Over long time horizons, even small angular errors compound. If we mean to steer the future well, we must first know which way to go. So let’s align the compass, then walk.

This (and references therein) suggests that we should still be clueless about whether (even) ontological longtermism would do more good than harm overall. This is for the same reasons why we should arguably be clueless about other longtermist projects (a position which you seem sympathetic to?).

Curious what you think of this.

Thanks, this has been genuinely clarifying for me. I agree that Ontological Longtermism doesn’t resolve determinative unawareness. My claim is narrower: that we should treat unawareness itself as a first-order moral target. If cluelessness is the decision-level face of unawareness, then discovery—pursued humbly—still seems preferable to deliberate ignorance.

While I also agree that historical extrapolation can’t show that discovery reduces unawareness in any final sense—it often just moves our uncertainty to a deeper level—it’s still the only process that has ever changed what we’re unaware of. It could eventually make possible the kind of insight you describe (e.g. discovering a selection pressure that would flip X-risk reduction from undefined to positive).

Even if the overall unawareness remains large, discovery has at least made parts of it structured, which is what makes future moral progress possible at all. In that limited sense, I lean toward continued investigation over suspension.

Thanks for the reply :)

> It could eventually make possible the kind of insight you describe (e.g. discovering a selection pressure that would flip X-risk reduction from undefined to positive).

Absolutely, although it could also lead people to mistakenly think they found such insight and do something that turns out bad for the long term. The crux then becomes whether we have any good reason to believe the former is determinately more likely than the latter, despite severe unawareness. To potentially make a convincing case that it is, one really needs to seriously engage with arguments for unawareness-driven cluelessness. Otherwise, one is always gonna give arguments that have already been debunked or that are way too vague for the crux to be identified, and the discussion never advances.

I take your point, and you’ve convinced me that determinative unawareness lies at a deeper level than the cluelessness my essay addresses, blocking any strong global justification for discovery’s net goodness.

Still, the local value of certain activities—surviving, cooperating, preserving options, and discovering—seems hard to ignore. If one continues to think the long term warrants attention and effort, even without clear awareness of how to help, discovery remains a prudent direction.

In that sense, I see your essay as defining the upper bound of what we can justifiably claim to know, and mine as exploring what orientation remains coherent within that bound. Any such orientation can only ever be conditionally coherent, but refining our map is still a principled way to reduce arbitrariness and local cluelessness, even if we can never know absolutely whether mapping is a net good.