This article at Our World in Data arguing in favour of "cage free" hens includes this graph from the Welfare Footprint Project (which spoke at EAG 2023) which has a nice breakdown which concludes that cage free aviaries are the most humane option of three types of hen housing studied.

However, according to this analysis, hens in furnished cages have the lowest prevalence of excruciating conditions- not cage free.

Moreover I am not convinced the tables for disabling and excruciating conditions are correct. The underlying data is very limited; where there is data "analysis," TFA uses almost no statistical technique; in some parts the "confidence intervals" mostly consists of rounding to the nearest 5. Sometimes it's even worse than that and is mostly guessing.

Therefore the analysis is very subject to the researcher's own biases. I think it's very plausible the amount of time spent in excruciating and disabling conditions in cage-free aviaries could be underestimated, and the numbers for conventional and furnished cages overestimated. This would change the overall conclusions of the analysis.

Excruciating conditions

Vent injuries

As per the graph, caged hens of both cage types (conventional and furnished) have a much lower rate of something called "vent injury" than cage free hens.

Hens are aggressive towards each other, hence the colloquial term "hen pecked." This is also called "persecution." They peck at each others' skin and also each other's genitals. ("Vent" is a colloquial term for cloaca.) Vent injuries are painful, can become infected, and can be fatal.

Cage free aviaries fundamentally expose hens to each other and this exposes them to greater risks from persecution; cages protect them from each other.

However, in the analysis cage free aviaries are ranked very close to enriched cage, primarily because vent injury prevalence is dwarfed by the inclusion of extremely high rates of fatal acute peritonitis, which is a type of E. coli infection. But how accurate are those numbers?

Peritonitis

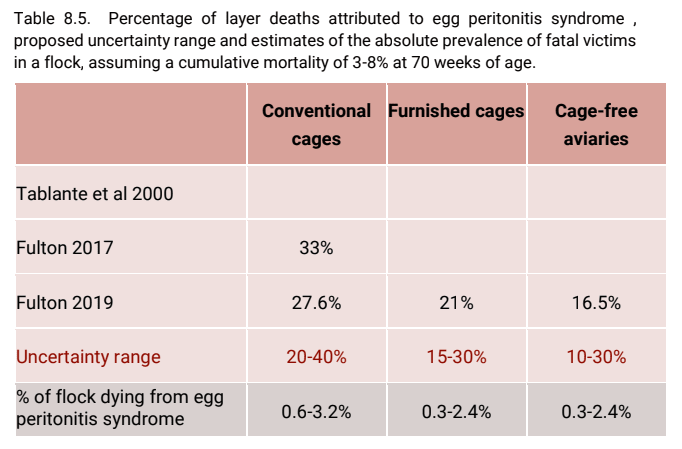

The Welfare Footprint Project used this table to explain their data on peritonitis:

You can see their only data comes from two papers from Fulton, 2017 and 2019, done on US farms. The "confidence intervals" overlap, so the difference is not statistically significant. The estimates are further based on assuming a cumulative mortality, not direct estimates of it. And both of those papers themselves concluded that enriched cages were more humane than cage free aviary hens (AV), writing in the 2019 paper,

Total mortality was greatest for AV, while CC and EC birds were similar. Keel bone fractures were greatest for AV... Infectious pododermatitis (bumblefoot) was most frequent for AV, next most frequent for EC, and essentially nonexistent for CC birds... Based upon these findings, it appears that EC housing is better for the health and welfare of egg-laying chickens than CC or AV housing.

(Bumblefoot was not included as a factor in the The Welfare Footprint's analysis, as far as I could tell.)

A quick google also found that in this one small study of Dutch farms, the rates of peritonitis found in free range farms, which included organic farms, was 10 times more common than it was in caged birds with mortality from peritonitis greater in free range and organic farms by a factor of at least 2 times relative to caged birds. This is opposite to the direction in the graph. However, there was only one caged farm in the analysis, so the data isn't conclusive by any means. But it does show that rate caged doesn't guarantee a higher peritonitis rate, either, nor vice versa.

I did also find a 2021 study on Portugal farms showing organic farms had the lowest peritonitis rate and caged birds the highest. This measured deaths on arrival to the slaughterhouse, not total rates, so absolute numbers can't be compared, but it does lend some weight to the direction of peritonitis rates regarding housing weight (towards the welfare org's side.)

There are also several more conditions in this paper, as with bumblefoot, that range from excruciating to hurtful as well, but don't seem to be included in the welfare footprint analysis at all. This could alter the results of the analysis.

Disabling pain

Moving on from excruciating to disabling pain, there are two main conditions that Welfare Footprint says contributed to the bulk of the time spent in disabling pain: keel bone injuries and nest deprivation. In the Welfare Footprint's analysis, cage free aviaries were the winner, but enriched cages only very slightly behind. The bulk of the "win" for cage-free is down to less nest deprivation.

Keel bone fractures

The keel bone in a chicken is a bone in the chest area. Keel bone fractures are the most common in cage free aviaries and least common in conventional cages. It's not clear why keel bone fractures are so prevalent in commercial laying hens, but research suggests it's due to increased laying.

But cage free aviaries result in more of these kinds of injuries, whilst still requiring frequent egg production. Some posit because these aviaries are crowded with multiple levels, so hens are often pushed or fall off the upper levels.

Keel bone fractures affect the ability of both the animal to walk comfortably as well as rest comfortably.

Nest deprivation

Nest deprivation has two components; in traditional caged birds, the cages are unfurnished. A furnished cage has a nest, but the bird might be excluded from it to increase egg production. In free range, each bird probably doesn't have their own nest either; UK regulations stipulated 1 nest per 7 birds, for instance.

Essentially this means that hens are prevented from sitting on their eggs; the eggs are instead taken away. Behavioural studies shows this does stress the hens.

I couldn't assess the accuracy of the nest deprivation numbers because unlike with the peritonitis data, I couldn't find their sources for these data. Since this is a critical piece of data for distinguishing between cage free and caged, this is pretty worrisome for its conclusion.

I also question whether nest deprivation is indeed comparable to keel bone fracture. Intuitively they don't seem comparable. Given that is basically accounts for the entirety of the difference in time spent in disabling conditions between cage free and caged hens, this is suspect.

Which is the most humane?

There's a clear argument to be made that cages might be safer for hens, because they may protect them from a range of excruciating and disabling conditions common in cage free aviary hens, such as keel bone injury and injuries caused by persecution from other hens. Some papers suggest they even have a lower mortality rate (i.e. Fulton 2019).

But it also might not change our conclusion of the analysis, since many hours spent in hurtful or annoying conditions such as movement restriction could easily outweigh the excruciating and disabling conditions, the former of which tends to be fairly time-minimised (in minutes), depending. However, it does muddy the water more than the original analysis does.

Welfare Footprint says they did not measure positive experiences for simplicity's sake or mortality rate. This is fair. However I wonder to the extent to which this was subtlety shoe-horned in. Allowing a broody hen time to nest is certainly a positive experience for hens. So does allowing them time to engage in foraging behaviour. Framing these as "nest deprivation" (disabling) or "foraging deprivation" (hurtful) allows them to be included in the analysis. However I don't think it makes sense to include these as a function of time, because there are threshold effects from this deprivation. Keeping them from doing certain behaviours entirely certainly causes stress, restricting it only sometimes is likely acceptable and doesn't cause a level of distress which is disabling or hurtful.

A keel bone fracture is painful for the duration of time a hen has it, but a hen deprived of foraging at night for an hour is perfectly fine. So the direct comparison seems strange.

(Of note, the welfare org has a very nice calculator where you can adjust the percentages yourself: https://cp.pain-track.org/hens)

The Welfare Footprint made an ambitious analysis and it's clear they did a great deal of work. But they also did not seem to analyse or were missing several painful conditions in chickens, such as bumblefoot, coccidiosis, or infectious diseases such as bird flu. Critically, these are conditions that may be more common in aviaries than in caged birds and could change the results of the analysis.

They also didn't and couldn't use high quality evidence or statistical techniques. This was partly due to paucity of the underlying research. They are not unaware of this. The ranges in the periodonitis data provided were particularly hacky with the statistical technique seeming to be "multiply by a constant and round to the nearest 5%".

It also makes me question the legitimacy of this type of of approach overall. It is far too easy to come to an opposite conclusion using the exact same data, or for new data that's not currently available to completely change the results of the analysis.

What are some better approaches to this kind of research? Mortality is often a good indicator that there are welfare problems with the conditions the hens are living in, even if you don't add it explicitly to the analysis. Some studies found mortality rates are higher in cage-free systems which suggests they are indeed less humane.

But a 2021 meta-analysis looked at this issue and didn't find a difference in mortality between caged and cage free systems, but only if the hen's beaks were trimmed in cage free systems. Otherwise, mortality was higher in cage free systems. This suggests that in practice cage free systems are worse overall.

Where differences in mortality across housing systems were found[ 7], they became nonsignificant when the confounding effect of beak trimming status was controlled (although beak trimming is a painful procedure with important negative effects on hen welfare[13],[14], its impact on reducing mortality due to injurious pecking is well known[15]).

Welfare Footprint's take on this paper takes this as a win for their point, but I think it rather shows they needed to include beak trimming in their model and the problems with this type of analysis in general.

I also think that perhaps the most humane conditions don't always come down to housing type. The meta-analysis found that death rates decreased with farmer experience more than housing type.

The huge variability in peritonitis rates depending on country (or study) with respect to housing type shows that implementation might be more important. Furnished cages might be well managed and kept clean and safer than cage free aviaries, but perhaps they're more vulnerable to bad farming practices such as neglect.

I do think it's important not to throw the baby out with the bathwater when it comes to furnished cages. They may have a place in at least some situations.

Bird flu epidemics often also sometimes require that birds be kept indoors. In the UK last year, birds were kept indoors for more than 3 months, meaning there were technically no free range eggs available in the country and the eggs were labelled barn eggs instead. Especially in such situations when hens are otherwise being kept inside, at least some time spent in furnished cages might actually be good, and is superior to barn conditions where hens do not have adequate space to avoid vent pecking. In such scenarios, free range eggs were likely experiencing worse conditions than eggs sold from furnished caged hens because they were living in barn conditions.

Comment

This is a draft amnesty post so there may be factual errors! Please comment if you find one.

Thank you for your thoughtful analysis. This is helpful for us to understand areas that must be improved or made clearer. This is especially important as we will be soon publishing the full Welfare Footprint of the Egg (various systems), where we analyse over 120 experiences (diseases, injuries, deprivations, imbalances – nearly everything we could identify), in different housing systems, from birth to slaughter (more info here), for layers and breeders.

On your specific points on the direction of the results: there are various ways in which the existing analysis was conservative (i.e. favored caged systems). For example, in estimating the prevalence of keel fractures and other ailments in cage-free systems, we considered prevalences as they were reported, which typically was in the first few cycles of experience with cages. Evidence indicates that these prevalence rates go down as management experience increases (examples in the Prevalence Chapter), yet we preferred not to make that assumption and use the data as it was. Also, we did not take into account positive welfare (greater in cage-free settings) and more diffuse experiences, like fear, helplessness and boredom (greater in cages). Nor did we consider the flow-through effects of frustrations from behavioural deprivations beyond the period corresponding to the time budget of engagement, or practices like induced-molting (more likely in cages), or the longer cycles of caged-hens (with end disproportionally worse at the end)

Importantly, there is substantial evidence indicating that Pain is more intense (and healing delayed), even for the same injury/disease, in cages than in cage-free systems. We did not consider these modulatory effects, but they are likely present. That said, we’ll look deeper into the references you mentioned.

Unfortunately, many existing comparisons of cage and cage-free cite the CSES studies, to which the analysis from Fulton are part of. These studies were funded by the American Egg Board and facilitated by another industry-funded organization focused on building consumer confidence and maintaining the industry's viability. While management in the caged systems was good and based on decades of experience, the cage-free systems were implemented for the first time, and did not adopt nearly any of the good management practices required. For example, during the laying phase, birds in the aviary were confined for many weeks before accessing the floor litter (something that makes injurious pecking much more likely). Also, insufficient space allowance and perch space in the aviary led to crowding, collisions, and failed landings, likely contributing to the high rate of keel injury and mortality. The authors themselves declared publicly they were still learning about what to do in the aviary systems during the research, which led to many failures. These design and management failures likely substantially inflated the negative outcomes in CF systems, including mortality (mortality data is also inconsistently reported in their publications, with some mortality - e.g. during placement - apparently excluded from caged systems).

Some info that may be useful:

More generally, both in the prior analysis, and in the forthcoming book, a major issue is data scarcity. Therefore, we inevitably rely on estimating uncertainty ranges for parameters like duration and prevalence. Inter-rater agreements should be made available together with future estimates, but what we have seen so far shows reasonable levels of agreement among WFI and independent academic raters/estimators.

As we build more comprehensive analyses, we’d be keen to have our estimates scrutinized as you did, so thank you!

Thank you very much for this thorough analysis and for the constructive comments.

Cynthia will address the points related to the results of the study, while I’ll focus here on the methodological aspects.

One of the most important points you raise touches on the core of the Welfare Footprint Framework itself: we recognize that inferring the affective states of other beings is enormously challenging—both in scope and depth. This task can never be complete; it will always require revisions and corrections as new evidence becomes available. The Welfare Footprint Framework is, in essence, an attempt to structure this challenge into as many workable, auditable pieces as possible, so that the process of inference can be progressively improved and openly scrutinized.

You are absolutely right that several painful conditions in chickens were not included in this initial analysis. This was a conscious decision—not because those harms are unimportant, but because we had to start with a subset that we judged to be among the most influential and best documented. The framework is designed precisely so that others can build upon it by incorporating additional conditions, refining prevalence estimates, or reassessing intensities. In that sense, this work should be seen as a living model, not a closed dataset.

Regarding the concern about the lack of use of high-quality statistical techniques, our approach is pragmatic. Where robust statistical analyses are feasible—such as in estimating prevalence or duration—they are of course welcome and encouraged. But in areas where measurement is currently impossible—most notably the intensity of affective states—we deliberately avoid mathematical sophistication for its own sake. No amount of elegant equations can compensate for the fact that subjective experience is, for now, beyond direct measurement. What we can do is gather convergent evidence from different sources - e.g. behavior, physiology, neurology, evolutionary reasoning - and generalize that evidence into transparent, revisable estimates, and make every assumption explicit so that others can challenge and adjust them.

As for the legitimacy of this approach, we believe that, while imperfect and always improvable, quantifying affective experiences is vastly more informative than relying solely on indirect indicators such as mortality. Animals can live long, physically healthy lives that are nevertheless filled with frustration, chronic pain, fear, or monotony—forms of suffering invisible to metrics that focus only on death or disease. By directing efforts toward gathering as much evidence as possible to infer the intensity and duration of each stage spent in negative and positive affective states, we can begin to capture what actually matters to the animal.

The framework has also evolved since this analysis was first produced. At that time, we focused primarily on negative affective states, but we have now extended the methodology to include Cumulative Pleasure alongside Cumulative Pain. Positive affective states are now being systematically quantified using the same operational principles, creating a fuller picture of animal welfare.

Finally, we are developing an open, collaborative platform where Pain-Tracks and Pleasure-Tracks can be published, discussed, and iteratively improved by the broader scientific community. Each component of a track—for example, the probability assigned to a certain intensity within a phase of an affective experience—could be challenged and refined, potentially even through expert voting or consensus mechanisms. The aim is to make welfare quantification transparent, dynamic, and collective rather than proprietary.

Thanks again for putting our work under the microscope—this is exactly what it needs. The Framework is meant to evolve, and feedback like yours helps it grow in the right direction.

Thanks for writing this up! I'd be interested to read a response to these points.