I often use the following thought experiment as an intuition pump to make the ethical case for taking expected value, risk/uncertainty-neutrality,[1] and math in general seriously in the context of doing good. There are, of course, issues with pure expected value maximization (e.g. Pascal’s Mugging, St. Petersburg paradox and infinities, etc), that I won’t go into in this post. I think these considerations are often given too much weight and applied improperly (which I also won’t discuss in this post).

This thought experiment isn’t original, but I forget where I first encountered it. You can still give me credit if you want. Thanks! The graphics below are from Claude, but you can also give me credit if you like them (and blame Claude if you don’t). Thanks again.

Thought experiment:

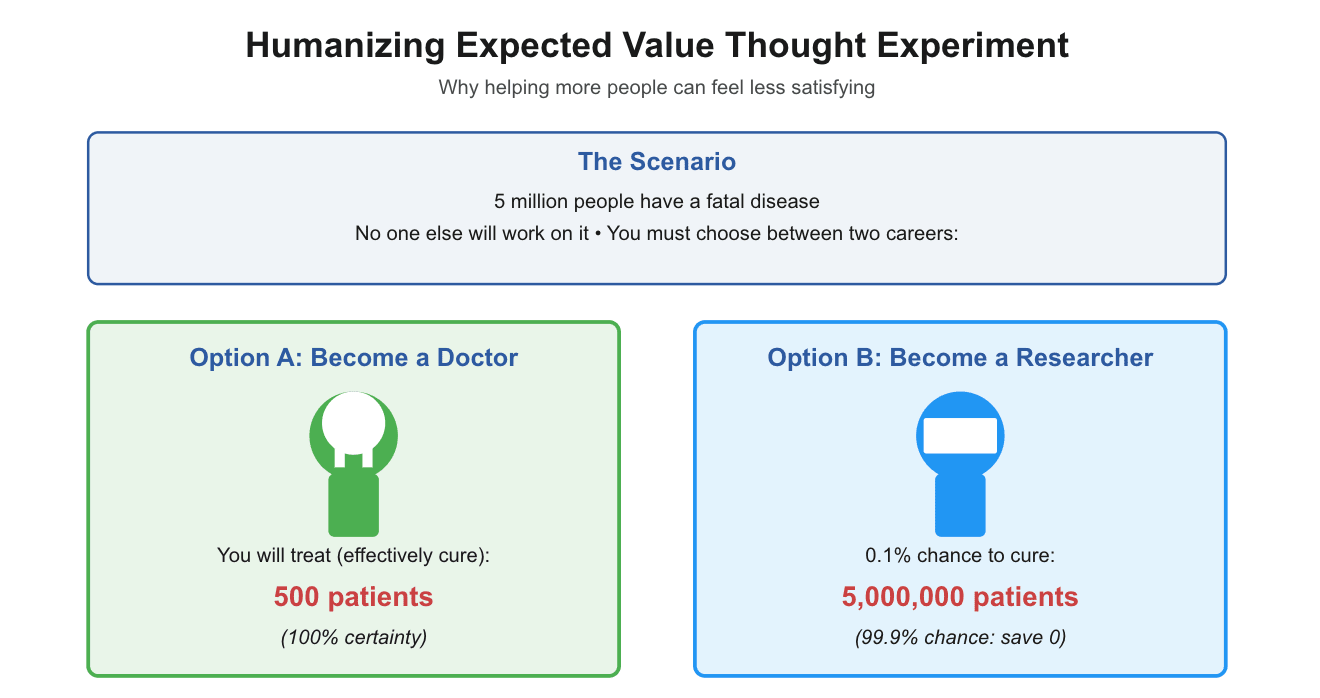

Say there's this new, obscure, debilitating disease that affects 5 million people, who will die in the next ten years if not treated. It has no known cure, and for whatever reason, I know nobody else is going to work on it. I’m considering two options for what I could do with my career to tackle this disease.

Option A: I can become a doctor and estimate I’ll be able to treat 500 patients over the coming ten years, where treating them is equivalent to curing them of the disease.

Option B: I can become a researcher, and I'd have a 0.1% chance of successfully developing a cure to the disease which would save all 5 million patients over the next ten years. But in 99.9% of worlds, I end up making no progress and don't end up saving any lives. The work I do doesn't end up helping other researchers get closer to coming up with a cure.

Given these two options, should I become a doctor or a researcher? Many people intuitively would think: "Man, saving 500 patients over the next ten years? That's definitely a career I can be proud of, and I’d have a ton of impact. With Option A, I know I'll get to save 500 people, and with the other option, there is a 99.9% chance that I don't end up saving anyone. Those odds aren’t great, and it’d be pretty rough to live my life knowing in all likelihood I won’t end up saving anyone."

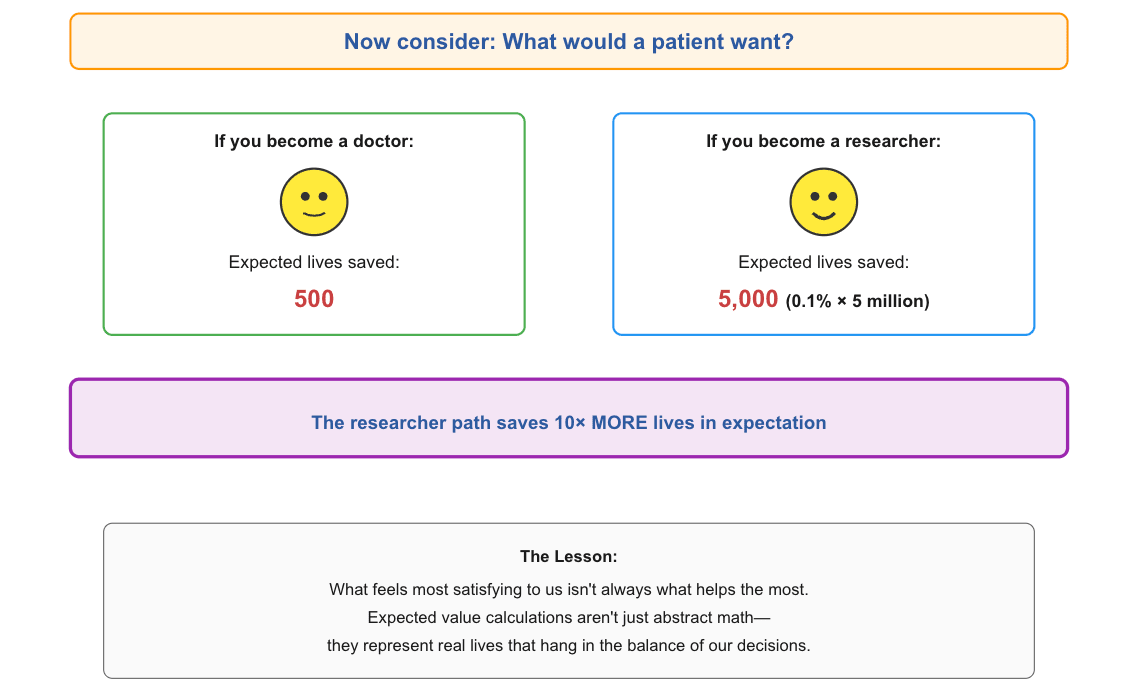

But consider the perspective of a random person with this disease. From their perspective, since they know that the doctor will save 500 patients out of the 5 million who have the disease, there is a 0.01% chance that they would get treated/cured if I chose to become a doctor. However, their chances of getting cured are 0.1% if I choose to become a researcher. So from their perspective, they would be ten times more likely to survive, if I choose to become a researcher instead of becoming a doctor.

This thought experiment simplifies things a lot, and reality is rarely this straightforward. But it is helpful for putting things in perspective. If what seems best to me as an altruist differs from what seems best to the beneficiaries I’m trying to help, I should be skeptical that my intuitions and preferences are actually impact-maximizing.

It also humanizes expected value calculations and all the math that often comes up when discussing effective altruism. To us, multiplying 5 million by 0.1% can just feel like math. But there really are lives at stake in the decisions we make, whether or not we see them with our own eyes.

I want to be serious about actually helping others as much as I can – and not be satisfied with doing what feels good enough. It’s extremely important to be vigilant about cognitive biases and motivated reasoning, and try my best to do what’s right even when it’s hard. Unlike with my thought experiment, many moral patients - especially animals and future sentience - won’t (and often can't) tell us when we could be helping them much more. We need to figure out how ourselves.

- ^

I think being downside-risk/loss-averse is usually more justified than being uncertainty-averse. If anything, given general dispositional aversion to uncertainty, I think prioritizing higher-uncertainty options is often likely to be the correct call altruistically speaking (especially when the downsides are lost time or money like in the above example, as opposed to counterfactual harm), since said options are more likely to be neglected. This seems to be the case in the EA community (especially in GHW and animal welfare), and the rest of the world.

Nice post and visualization! You might be interested in a different but related thought experiment from Richard Chappell.

Ooh this is neat.

I like how it neutralizes the certainty-seeking part of me since it's only me, the difference maker, that has the option of a guaranteed 100% outcome. For the beneficiary, it's always a gamble.

Thanks for this!

First came across a similar argument in Joe Carlsmith's series on expected utility (this section in particular). The rest of that essay has some other interesting arguments, though the one you've highlighted here is the part I've generally found myself remembering and coming back to most.

I think this post would be pretty helpful (short yet string argument) for a (university or other) intro fellowship -- if you can add/substitute a reading to your current intro fellowship, consider adding it to yours!

The argument sure is a string :P

Very good thought experiment. The point is correct. The problem is that in real life we almost never know the probability of anything. So, it will almost never happen that someone knows a long shot bet has 10x better expected value than a sure thing. What will happen in almost every case is that a person faces irreducible uncertainty and takes a bet. That’s life and it ain’t such a bad gig.

Sounds like a cause X, helping people gain clarity on tractable subsets of the general issue you mentioned... although as I write this I realise 80K and Probably Good etc are a thing, their qualitative advice is great, and they've argued against doing the quantitative version. (Some people disagree but they're in the minority and it hasn't really caught on in the couple of years I've paid attention to this.)

I think the uncertainty is often just irreducible. Someone faces the choice of either becoming an oncologist who treats patients or a cancer researcher. They don't know which option has higher expected value because they don't know the relevant probabilities. And there is no way out of that uncertainty, so they have to make a choice with the information they have.

You can't know with certainty, but any decision you make is based on some implicit guesses. This seems to be pretending that the uncertainty precludes doing introspection or analysis - as if making bets, as you put it, must be done blindly.

No, irreducible uncertainty is not all-or-nothing. Obviously a person should do introspection and analysis when making important decisions.

absolutely love this perspective and i will definitely use a version of it in future explanations. thanks a lot!

You never miss Kuhan!