This post is aimed at future university group organizers, but others (e.g. funders, other fieldbuilders) might find it valuable

Takeaways

- More students might be interested in AI safety than you think. Our group attracted way more interest than expected. We hoped to “get 1-3 students excited about AI safety,” but our events averaged 30+ attendees each and 50+ people participated in our programs during our first academic year.

- Translating interest into action is hard. It’s unclear how UBC AI Safety impacted program participants’ career trajectories. Based on what little evidence we have, the effect seems significant but not huge.

- Communicate precisely. We started the group with a broad definition of “AI safety,” including extinction and catastrophic risks as well as issues like bias, misinformation, and deepfakes. This led to most of our membership focusing primarily about present-day risks from AI. Later, we focused our programs on extreme risks, but it’s not clear how well this was received.

- A committed team is essential, and quality attracts quality. Through luck and networking, we formed a strong team of four before launching our group. When we hosted our ‘launch event,’ three attendees asked to volunteer with us.

- Starting a group is a gateway to the AI safety community. Our university and city don’t have many people working in AI safety. For some of us, organizing was the first step that connected us to AI safety communities across the world, including conferences, workshops, and fellowships.

- Running good programs takes a lot of time and effort. The planning fallacy can hit hard when you’re running programs for the first time. Remember that you can’t do it all and prioritize ruthlessly. This can mean prioritizing certain programs over others, or it can mean prioritizing your own career development over your group.

Intro

We’re Lucy and Josh, co-founders of UBC AI Safety at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver, Canada.

In May 2024, we attended a three-day workshop in the Bay Area called Global Challenges Project, where we met some AI safety university group organizers. They showed us that starting our own group would be achievable and impactful. We noticed that despite having a strong computer science program at UBC, there was no visible AI safety community on campus or in our city. In our final year of undergrad, we changed that.

Here’s an overview of this post:

- How we did on our goals, and what we learned about converting interest into action.

- How to launch your group, from finding co-founders to hosting your first event.

- Details on our technical intro program, policy reading group, technical upskilling program, and discussion group: what worked, what didn’t, and our session plans for you to copy.

- Tips for running good events and effective outreach strategies (department newsletters beat everything else).

- Managing finances, booking venues, succession planning, and other things we wish we'd known earlier.

- How to grow the field while not neglecting your own AI safety career development.

This is a long post. Sections are readable in isolation, so please feel free to skim and jump between sections.

We got way more interest than expected

Before the academic term started, we wrote down these goals for the year:

- Get 1-3 students really excited about AI safety, establishing the initial core group and planning the group’s next steps.

- Create an environment where high-quality conversations about AI safety happen weekly.

- Establish a visible presence on campus such that people already interested in AI safety can congregate.

- Within 2 years, 4+ people are now actively working on AI safety because of the group’s existence and 15+ take the idea more seriously.

Spend time operationalizing your goals, and make a plan to track your progress on those metrics (e.g., attendance and survey responses). These goals aren’t well specified, making it hard to measure success.[1]

That said, on almost all metrics, we exceeded expectations. Here are some concrete things that happened in our first academic year:

- We built a leadership team of 12 people.

- ~50 people participated in our programs.

- 150+ people joined our Slack.

- We ran three social events with 30-50+ attendees each.

- We organized several weekly programs to facilitate conversations about AI safety.

- We became the first Google search result for “UBC AI safety.”

- We made connections with departments, research groups, professors, and other student clubs at our university.

Why the strong interest?

- We started the group as LLMs were becoming increasingly popular.

- UBC has over 60k students, including a strong CS department. It’s a big school with more than double Harvard’s student population.

- The school is socially liberal, and many students are concerned about issues like bias, discrimination, and fairness, which UBC AI Safety is inclusive of.

Despite the interest, we’re not seeing much action

(This section reflects Josh's personal assessment based on limited evidence — Lucy and others on the team may have different views.)

We know ~7 former group participants who are now actively working in AI safety. Several others are applying for relevant entry-level roles, internships, and upskilling programs. Correlation does not equal causation, but we’d guess UBC AI Safety played a causal role in at least some of these career decisions.

But given the strong interest we’ve seen, I (Josh) would have expected more of our members to be actively pursuing AI safety careers.

One of the arguments that convinced me to start UBC AI Safety was the multiplier effect. I put some weight on an optimistic hypothesis: because university students often put so little thought into their career choice, exposing them to strong arguments about AI risk will be enough to cause many to pursue AI safety careers. We got some data that goes against that hypothesis.

After the first and last session of our technical intro program, we had participants anonymously rate their agreement[2] with this sentence: “I intend to pursue a career mitigating global catastrophic risks from advanced AI.”[3]

Session 1 (22 responses):

- Mean: 3.41

- Median: 3.5

Session 7 (16 responses):

- Mean: 3.69

- Median: 3.5

The difference isn’t big. We might have had a modest impact on participants’ career plans, but it seems unlikely that our impact was big. As a facilitator, I didn’t get the qualitative impression that people were changing their career plans, either.

This was surprising for me. I came in believing AI has a double-digit chance of causing extinction within a decade, making AI safety extremely urgent and important. I was confused why our participants seemingly weren’t seeing it that way.

What might explain this?

- AI safety careers don't feel attainable.

- People recognize early on that AI Safety opportunities, especially paid ones, are very competitive and there are less openings compared to many more traditional career paths.

- UBC AI Safety doesn’t have the compelling success stories that other schools do, like Harvard or UC Berkeley, some of whose AI safety group alumni have great AI safety jobs.

- There's a lack of institutional support. UBC lacks faculty interested in AI safety, and there are no significant AI safety organizations in the city (or Western Canada at large).

- Some students face real constraints: financial pressure, family expectations, etc. that prevent them from entering a career with considerable uncertainty.

- Our members don’t believe in the importance of AI safety strongly enough to upskill independently without pay while applying for roles.

- It often takes months to years of exposure to fully internalize AI risk arguments.

- Taking ideas seriously enough to restructure your life around them is rare.

Other AI safety groups facilitate career change by creating a pipeline of programs that take people from curious to getting great opportunities. We took a step in this direction in the form of our technical upskilling program based on the ARENA curriculum. A couple of alumni expressed interest in applying to AI safety fellowships but we haven't heard about any acceptances yet.

We also tried twice to get our technical intro program participants to do project sprints but saw little interest. The first attempt was an optional project component during reading break. A few participants expressed interest, but no one actually did any projects. The second was more like a mini hackathon, and only two people showed up. What went wrong? Reading break wasn’t the best time for a project sprint, and our mini hackathon was held in the week before finals with no mentorship. And instead of asking students to take extra time out of their busy schedules midway through the program, we could have made the project sprint a mandatory component of the program and communicated this upfront.

To improve this, our successors are planning to:

- Introduce students to competitive skills early on:

- Create a skills repository that maps prerequisites for programs like SPAR to research opportunities at UBC.

- Integrate these prerequisites into programs as a low-friction way to build knowledge.

- Build tangible portfolios:

- Add a project component to each technical and governance program (e.g., blog post, paper replication).

- Provide pre-scoped ideas with clear success criteria to increase the chances of polished outputs we can showcase on our website.

- Strengthen community ties:

- Host regular 1-on-1s and monthly dinners with people in Vancouver working in AI safety to build relationships and encourage mentorship.

- Showcase community success stories, including UBC members’ published work and profiles of non-UBC collaborators, to create visible role models.

Getting started

Do the Pathfinder Fellowship. Before the school year started, we did FSP, now called the Pathfinder Fellowship. This gave us the resources we needed to prepare for the year, including help applying for funding,[4] planning, and setting up systems for our group.

Make a website. Josh made a website, which has paid dividends. He used this template. It took less than a day to set up and didn’t require writing any code. We recommend other groups do this; it makes your group look official and allows people to find you by Googling [your university name] + “AI safety.”

Use relevant university clubs, Slacks/Discords, and events to build your initial team. We didn’t know many others interested in AI safety at UBC, so we found people to join our leadership team by asking around at relevant events, at UBC’s EA Club, and in relevant Slack/Discord channels. We asked everyone we talked to if they knew others who might want to join us, but most didn’t. Nonetheless, we quickly formed a committed and skilled team of four. We’re incredibly grateful for our luck!

Consider hosting a launch event. Early in the school year, we hosted a launch event. We promoted it quite a bit and ended up with over 50 attendees, which blew us away. With four team members, uncertain funding, and a lot of homemade sandwiches, we put on a successful event. Three people offered to volunteer with us during the event, two of whom became core team members by the end of the year. Without really understanding this at the time, our demonstration of competence attracted other competent people.

What we wish we’d known

Decide which risks your group is about. Our leadership team had a variety of concerns about AI, from extinction to autonomous warfare to deepfakes. We decided to be explicitly inclusive of all these concerns, with an emphasis on catastrophic and existential risk. We didn’t realize this would result in extinction risk-focused people being consistently outnumbered in our group. This led to a tug-of-war where most of our members wanted us to talk more about the present-day risks, which was not our intention when starting the club. If you want to focus your group on catastrophic risks, consider starting small, solidifying large-scale risks in the culture of the group, then expanding.

Try hard to avoid wasting time with meetings. As we onboarded more people to our team, we moved from inviting everyone to weekly leadership meetings by default to only people who needed to attend. This freed up time for our volunteers and made meetings more productive.

The planning fallacy hits harder than you think. Riding the wave of our launch event’s success, we tried to do too much too quickly. Team meetings produced more good ideas than we had capacity to execute. We prioritized ruthlessly, but even then, our programs took more time and energy to run than we thought.

Find venues early. We continuously struggled to get venues for our events and program meetings. We decided not to become an official UBC club because it involved annoying bureaucratic red tape. However, being an official university-affiliated club would have given us access to booking more venues easily. Save yourself from the continuous headache by doing what it takes to book good locations early at your university, whether that means making friends with grad students or professors, emailing student residence building managers, finding students with special booking privileges, etc.

Do succession planning early. We knew we were graduating, and we knew we had limited time to identify successors to take over the group, but it was still hard. Reach out to chat with your most engaged members 1-on-1 and check for interest and fit. Then, before the school year is over, have every team member write thorough documentation for their role. Finally, celebrate the hand-off — we regret not doing an end-of-year leadership social.

Programs

In first semester (Sept-Dec), we ran:

- Four technical intro program groups

- A weekly policy reading group

- A casual weekly discussion group

- Two big social events

- One speaker event

In second semester (Jan-Apr), we:

- Ran two technical intro program groups

- Maintained our policy reading group

- Maintained our casual weekly discussion group

- Added a weekly technical upskilling program which followed the ARENA curriculum

- Organized one big social event

We chose our programs based on conversations with our FSP mentors, inspiration from other AI safety university groups, and facilitator preferences. We think we could have made our decisions more carefully.

Choose your programs systematically. Move from “Should we run a hackathon or a talk?” towards “Should we introduce more people to AI safety or try to produce a research output?” What does the world need, and what is your group ready to do? We’d recommend asking the following questions:

- What’s our group’s goal?

- Ours was to educate and empower people to work on mitigating risks from advanced AI.

- What are our program’s goals?

- For example:

- Introduce participants to key AI safety concepts.

- Explore ways (careers, volunteering, organizing a group, etc.) to contribute to AI safety.

- Deepen AI safety-relevant knowledge.

- Build career capital by networking.

- Produce an output that impacts AI safety.

- Our big social events were mostly about introducing participants to AI safety concepts and building career capital by networking. Our recurring programs were about deepening AI safety-relevant knowledge and exploring ways to contribute to AI safety.

- Choose these goals by thinking about what the field of AI safety needs and the value you’re providing participants.

- For example:

- How can we design our programs to accomplish our goals?

- This is where you decide on all the specifics. But those decisions will be easier to make because they’ll be guided by your goals.

Technical intro program

Our technical intro program involved:

- Weekly 2-hour meetings on campus with dinner provided

- ~1 hour of silent reading followed by ~1 hour of discussion

- No assigned work outside of meetings

- Small groups of ~6-8 people

For readings, we used the AI Safety Atlas (see our session plans here). Many other university groups use a combination of sources, like BlueDot Impact’s courses. We’re not sure which is a better choice.[5]

In our first term, we got 58 applications, which was way more than expected. We accepted 32 of them and made four groups, grouping people by availability and rough level of technical knowledge.

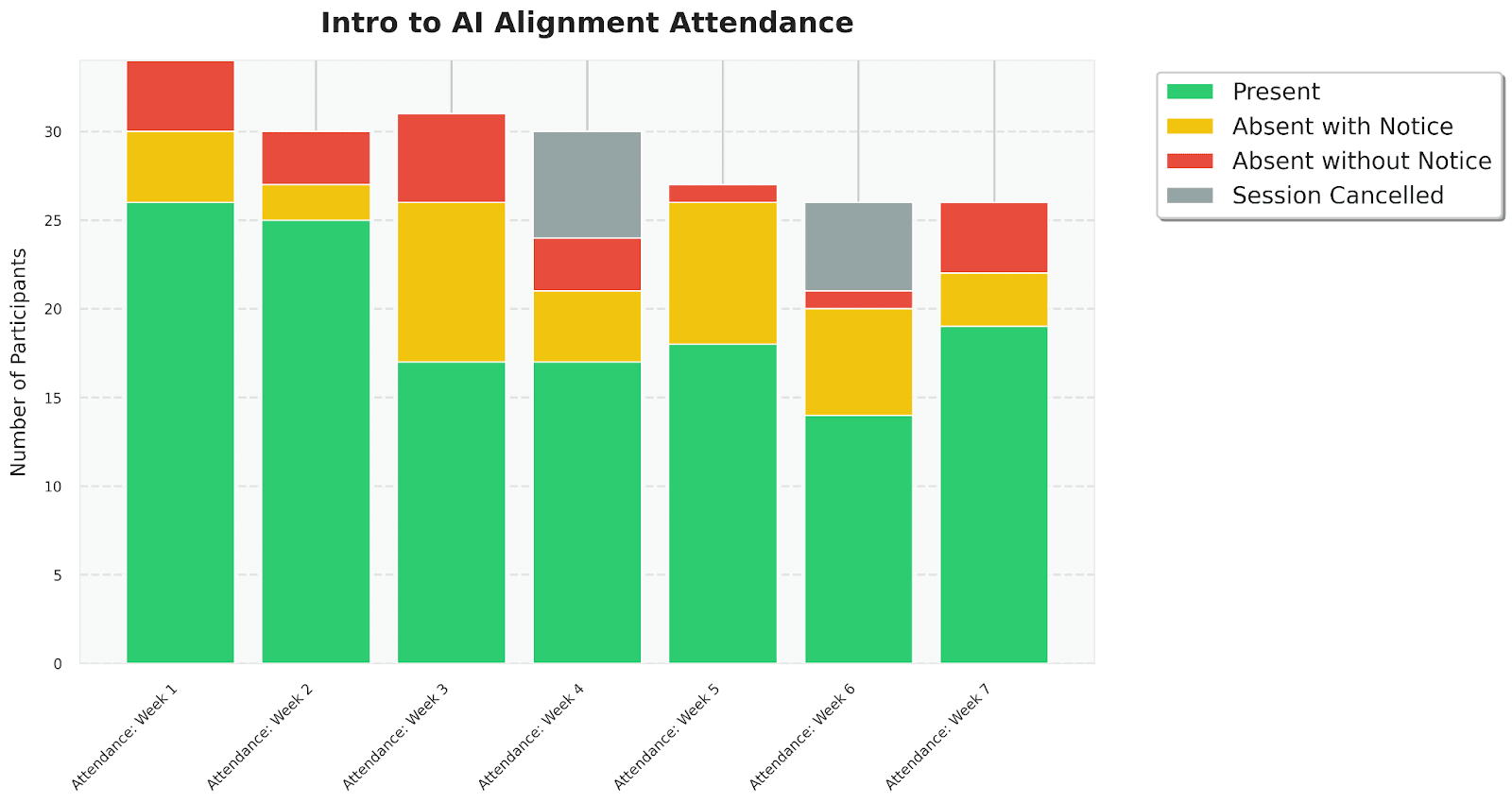

Term 1 attendance (Oct-Nov):

In term 2, we got 26 applications,[6] which we made into two groups. Only one participant from term 1 wanted to become a facilitator for term 2, which is less than we were hoping.

Term 2 attendance (Jan-Mar):

From what I’ve heard from other AI safety university groups, this is a pretty strong retention rate. We’re not sure why this is. One potential explanation is that not many clubs at UBC offer free meals.

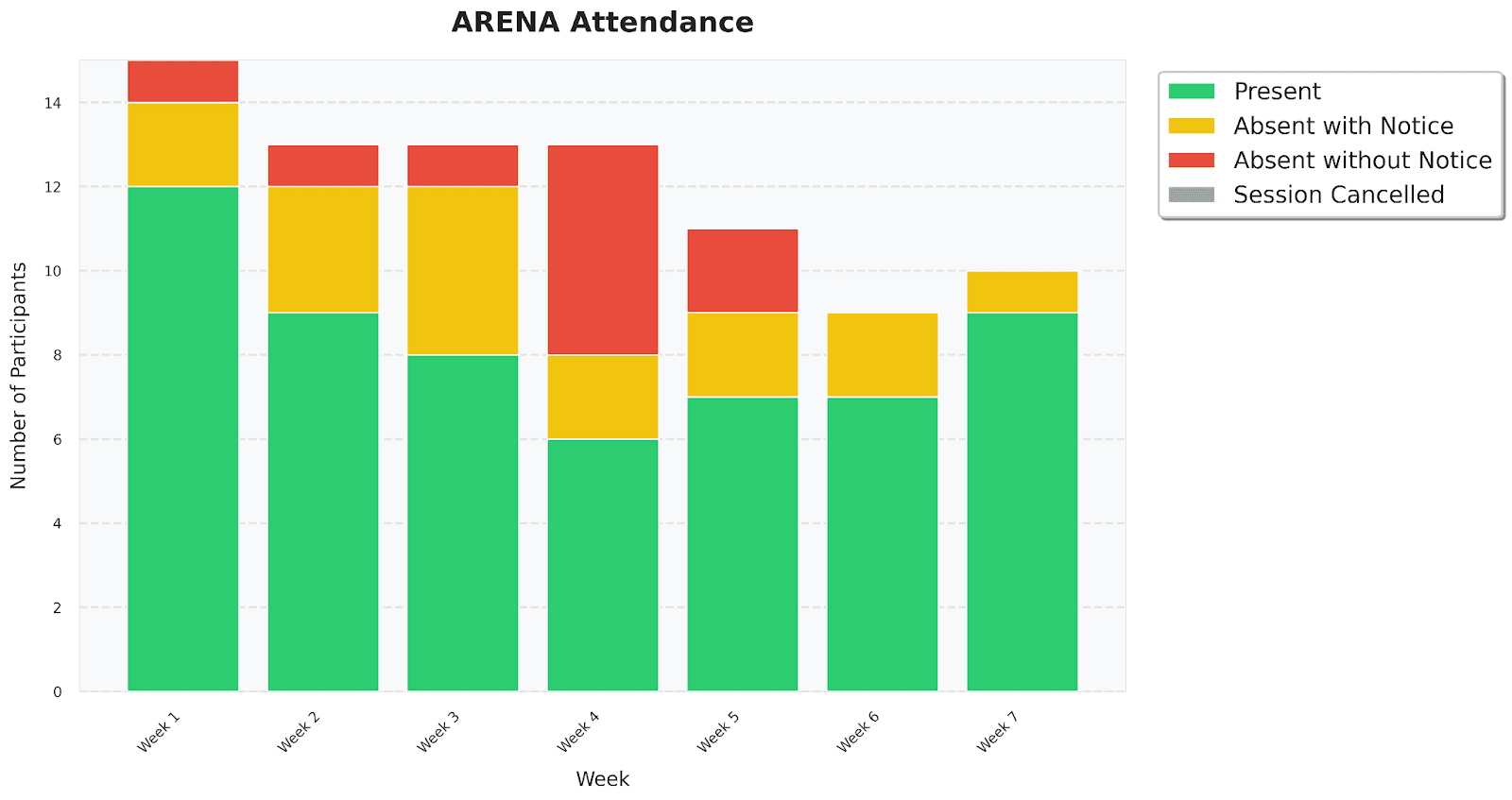

Policy reading group

We didn’t have facilitators to lead a governance intro program (like BlueDot’s AI Governance curriculum), so we opted for a weekly AI policy reading group.

Attendance was on a drop-in basis. We averaged around 5 attendees per session. We’d recommend running a higher-commitment program if you can.

For our reading group, facilitators chose readings and made a session plan every week. This took around 2-4 hours per week. See our session plans below:

First semester:

- Week 1: California governor Gavin Newsom vetoes landmark AI safety bill

- Week 2: The EU's AI Act Explained

- Week 3: AI and Data Act (AIDA)

- Week 4: Governing AI for Humanity - United Nations Report

- Week 5: Writer's Guild of America 2023 Strike

- Week 6: Future of AI Governance

Second semester:

- Week 1: What is AI policy? Examining Canadian and American Contexts

- Week 2: China and AI Policy: Context and Inquiry for Current Events

- Week 3: The Role of Scientists in AI Policy

- Week 4: Antitrust and Competition in AI

- Week 5: Challenges to Effective Policy in a Changing Political Landscape

- Week 6: The Narrative Engine: How Storytelling Drives AI Discourse

- Week 7: America’s AI Action Plan: What Stakeholders are Telling the White House

You’re welcome to use our program plans as you see fit. If you want to see a detailed breakdown of what aspects of the reading group went well and areas for improvement, reach out to us at ubcaisafety@gmail.com.

Technical upskilling program

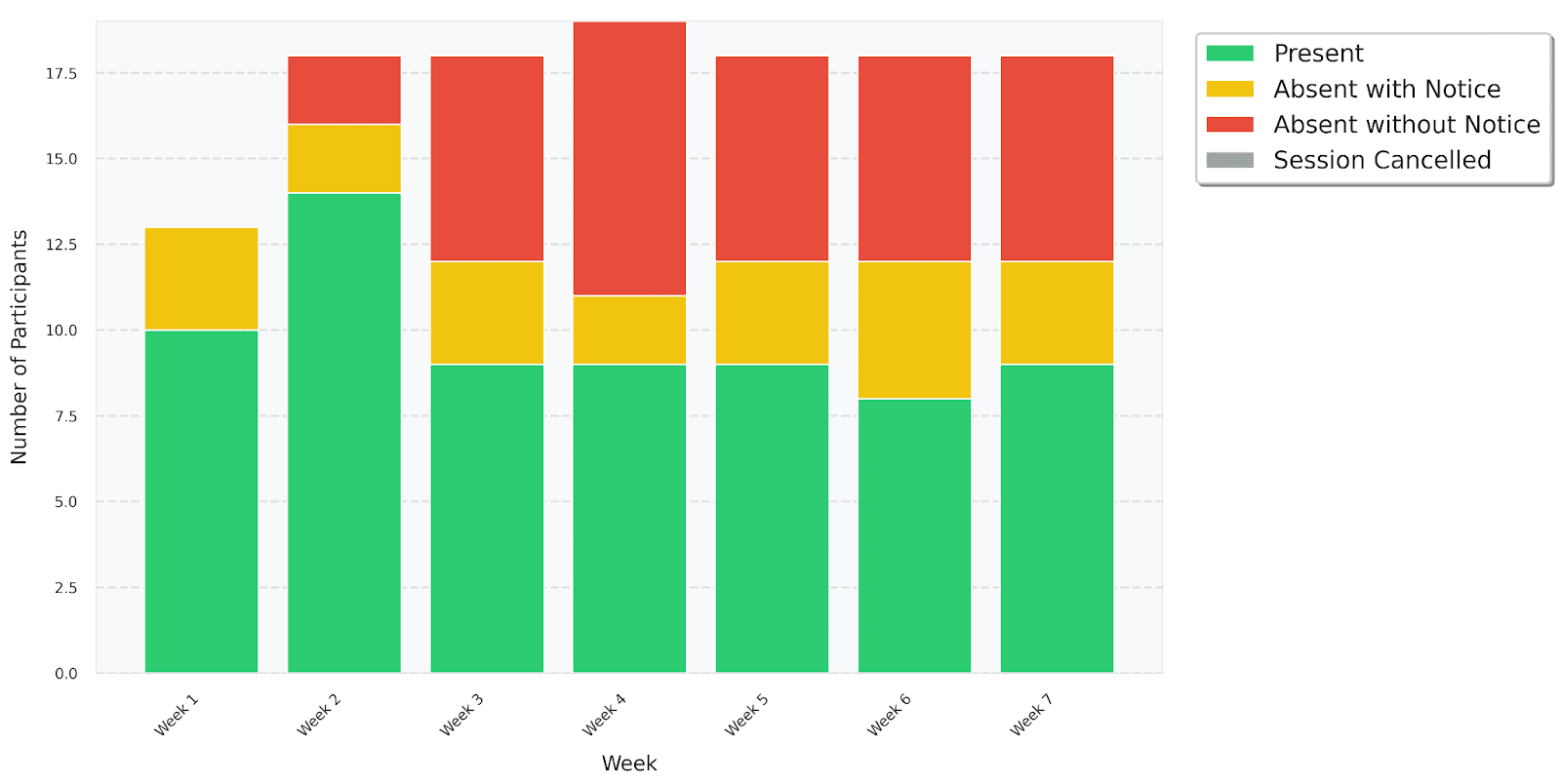

We ran a technical upskilling program based on the ARENA curriculum. We got 26 applications and accepted 15. Across 7 weeks, we met for 4 hours from 5-9pm on Thursday nights, with dinner provided.

We expected a sharp decline in the attendance, as other AI safety groups warned us might happen, but we were pleasantly surprised.

Here are the (lightly edited) reflections from our facilitator and TA, Justice, a CS PhD Student specializing in rare event simulation for RL and safety-critical systems.[7]

Is there anything you did to improve retention/prevent dropout?

We fortunately did not have much dropout throughout the term, which was great. I attribute it mostly to luck as I know that other AI safety university groups have had high attrition rates, and I don't think I did anything particularly novel to maintain retention. Providing food was probably the most important factor. I was also lenient about people's time, meaning that if people needed to come late or leave early, that was fine. Lastly, unlike groups at other universities, participants in our accelerator worked primarily independently and only pair-programmed when they were stuck on the same problem. While this meant that people got out of sync, it may have led to more "investment" in the material as they solved essentially all of the problems themselves.

How far did people get through the curriculum?

People only got halfway through Chapter 0. The average for other AI safety university groups was halfway through Chapter 1, I believe. But they were meeting for 8 hours per week while we only met for 4. A couple people are still meeting weekly over the summer and I expect them to get halfway through Chapter 1 by September.

How important do you think your background was for running the program?

My background definitely helped a lot for answering questions, giving advice, and providing broader context as the material is technical. I don't think it's absolutely necessary for facilitators to be active ML researchers in order to facilitate, but it certainly helps. A person who has completed the notebooks themselves and is well-versed in PyTorch should be able to facilitate.

What worked well?

I booked two rooms, one where people could ask questions without worrying about disrupting others and one for quiet work. This was helpful for those who wanted to avoid distractions. I also incorporated breaks in which we stretched and played short games.

What would you do differently if you were to run the program again?

5-9pm on Thursday is late and the students came into each meeting already tired from lectures all day and week. 8 hours on a Saturday or Sunday would have been more productive. It would be more difficult to fit into one's schedule, but dedicated students would have gotten more out of the program.

What do you think was the opportunity cost of your time running this program?

Instead of the accelerator, I would have TA'd, but the accelerator was a better use of my time because I got to review more practical fundamentals than I would have from TAing a course. Also, I spent less time overall doing the accelerator than I would have TAing, which gave me more time to do research. The ideal alternative would have been to get paid to do AI safety research directly, but unfortunately my LTFF application was rejected. In general I would recommend that AI safety researchers work directly on AI safety research instead of facilitate; however, because facilitating is not as cognitively demanding as being a participant (we're helping, not solving problems), if an AI safety researcher felt that spending a Saturday facilitating would not be detrimental to their productivity doing direct AI safety research the next week M-F, then facilitating could be fun and impactful.

If you’re thinking of running an AI safety technical research upskilling program, see this doc for insights from other groups (thanks to Jeremy Kintana for putting the doc together!).

Discussion Group

This was an experimental program somewhere between a reading group and a social. The idea was roundtable AI safety discussions every two weeks with topics crowdsourced from participants. Sessions were 1.5 hours, included basic refreshments, and drew around 6-9 attendees on average.

Participants had very diverse perspectives, which made it difficult to keep everyone on the same page during discussions. In general, we’d recommend hosting socials instead.

Events

We ran five major events across two semesters: three semi-structured social/networking events, one speaker event, and one one-day project sprint. Below are some lessons we learned about hosting good events. Feel free to reach out for reflections on specific types of events if you are planning one!

Decide on the goal of your event and its target audience. Similar to when choosing programs, this will guide the many logistical decisions you’ll need to make. Rather than just hoping people show up, do a target audience exercise. Think about their knowledge of AI, familiarity with AI safety, career stage, degree level, life stage, social group, etc. This will help you choose the event location, timing, and format. To give an obvious example, if your event is meant to help students consider careers in AI safety, don’t schedule it during exam week.

Add structure. Speaking from experience: at unstructured events, newcomers often feel lost without knowing who to talk to or who the organizers are, and conversations with random people are often not useful and hard to leave. Structure can help. For example:

- Icebreakers

- E.g. “What’s something you find interesting about AI safety?”; “What's a small thing that consistently brings you joy in your daily life?”

- This is useful for both building personal rapport and gauging AI safety familiarity. Effective icebreakers can quickly introduce participants to each other in a low-stakes way, offering many paths for further connection.

- See this page for more guidance and icebreaker ideas.

- Learning activities

- In a large group, this could often come in the form of a short presentation; smaller groups could consider a short reading and discussion.

- This is useful for sharing information about AI safety.

- Discussion

- Our program and event attendees consistently said they got a lot of value from group discussion time.

- Unstructured time

- There should always be free time to allow participants to make connections organically and follow their interests.

Structure keeps the event moving and gives people a natural point to find someone new to talk to. We’ve included an example event plan in the footnote.[8]

Get the details right. Besides structured activities, there are lots of small things that improve the quality of an event:

Look at the space and plan your setup before the event. If your tech setup is complicated and crucial to your event, we’d highly recommend doing a tech rehearsal.[9]

- Assign well-defined roles to each organizer who will be at the event.

- Show up to the event location at least an hour before the start time. You need time to set up, and at least one person will show up early.

- Adjust the space for flow. Removing chairs is often a good idea — people feel stuck in place as soon as they sit down.

- Put up signs so people can easily find the event and the bathrooms.

- Use name tags. They make everyone feel like they’re on the same team and prevent awkward questions like “What was your name again?”.

- Introduce the organizers so people know who to come to with questions, and ideally decide on a common identifier (e.g. outfit colour or special name tag).

- Don’t be afraid to physically move people around the space regularly, setting the social norm to be “mingling”.

- The best discussions usually happen in groups of 2-5. Break apart large groups and check in on people sitting alone.

- Schedule a time for a group photo before most people start leaving (around two thirds of the way into the event time seems ideal).

- Actively offer people the ability to give you feedback, and make it as easy for them as possible.

- No later than the day after the event, write down your reflections, including your observations, feelings, and thoughts.

There is no perfect event. Not everyone is going to resonate with your event, and that’s okay. Focus on getting through to the core group of people who would resonate. A good rule of thumb is that if the event went 80% well by the metrics that matter to you, it was a success.

Outreach

What we did:

- Internal marketing

- We advertised on our Slack and Instagram first (more details below).

- Department newsletters, e.g. the computer science students’ mailing list

- This was by far our most effective outreach method, and it was fairly easy to do.

- At the beginning of the semester, we emailed the UBC staff who run each department newsletter, introducing our group and providing an example blurb about our programs. Most were happy to help.

- Boothing at two clubs’ fairs

- This added around 100 people who expressed interest in our programs.

- However, it took a long time, and often didn’t reach the most promising people.

- Instagram

- Running our account took time, but it was worth it to fit in with our school’s norm. It’s very common at UBC for students to first ask for your club’s Instagram if they’re interested.

- We had a small team creating content for our page, e.g.:

- General information for new people to get to know the group.

- Leadership team profiles.

- Event posters, reminders, and recaps.

- After posting something, we would send it to relevant Instagram accounts (e.g. student organizations, related clubs) to repost on their stories.

- This seems to have been moderately effective.

- Sharing info on relevant Discord servers and Slack channels

- This seemed to help us somewhat.

- You could share your info to civil society AI safety groups, graduate student groups, or basically any group you can find related to computer science or policy.

- We also made a few classroom announcements (e.g. right before lecture starts for a relevant course), but results weren’t that strong

- Word-of-mouth

- Sending info in group chats and to friends seems worthwhile.

- One time, Lucy accidentally brought up AGI timelines with someone at a dance class. Turns out, he knew about AI safety, had relevant research experience, and was pretty cracked. He attended our events and was later accepted to MATS and the Anthropic Fellowship.

Some tips:

- Write for a target audience. Optimize your messaging for the people you want to attract.

- Market widely. When your materials are written, it doesn’t take much time to post them to several platforms. You can filter for your target audience later using e.g. program applications.

- Tell people you have free food. This is a big selling point for students.

- Keep an updated list of all your outreach strategies. This will come in handy for future semesters and new team members. This should include a list of everyone who’s expressed interest in your group.

We found faculty outreach difficult. We attended a few networking events with AI research groups, reached out to faculty from personal connections, and cold emailed a few professors with publicly legible AI safety history. Our efforts were limited because of time constraints and lack of clearly aligned faculty members.

Finances

We were supported by Open Philanthropy's university group funding program. Most of our budget went towards food.

Some lessons we learned:

- Budget per program, not per month.

- Set a reminder (automatable using Slackbot) for your team members to submit their receipts for reimbursement.

- If your group members are buying restaurant food using your budget, define standards for tipping.

- Provide clear guidance for what costs are reimbursable and what are not. For example, clarify whether transportation to an event would be covered by your budget.

- Doing a budget review at the end of each semester seems wise.

- We heard that American AI safety groups have to deal with lots of annoying tax paperwork, but as a Canadian group we didn’t have to do much at all.

Providing free dinner to members isn’t normal for UBC clubs — most have very little funding. This made the dinners we provided even more valuable to participants. To lower costs and stay close to the norm, we ordered pretty basic meals ($10-13 CAD per person per meal).

How not to neglect your own career growth

Group organizing can be a great gateway to the rest of the field of AI safety, so we’d encourage you to make time for your personal career development. This makes even more sense if timelines to AGI are short.

Run programs that support your learning. For example, our policy reading group facilitators often chose topics relevant to their own interests. If you don’t already have a similar program, you could start a low-effort, informal reading group to tackle the papers you’ve been meaning to read anyway. This way, you can do fieldbuilding and personal career growth at the same time. All you need are a few (accountability) buddies interested in the same readings.

Run co-working sessions. Similarly, you can organize simple coworking sessions for personal projects or applications to fellowships like MATS. These can be motivating and can help create a “working on AI safety” norm in your group.

Apply for AI safety opportunities. Lucy did the Pivotal Fellowship in London during second semester. This was a great chance for her to work on AI safety full-time, and it enabled connections between our group and the wider world of AI safety. During this time, other members of our leadership team took on more responsibilities. The team restructured to have program leads for each of our programs, and this worked out since most people were organized and didn’t need much oversight.

Talk to people working in AI safety. Being an AI safety group leader gives you a credential that can make it easier to reach out to professionals in the field. People are often more generous with their time than you expect, especially if they can share insights that are valuable to you. We recommend having a low bar to connect with them for the benefit of your group and career development.

Finally, check out these resources if you haven’t already:

- Map of AI Existential Safety

- Pay particular attention to Newsletter Nook, Training Town, Career Castle, and Resource Rock

- Sign up for the AI Safety Events and Training newsletter

- Join the AIS Groups Slack

Conclusion

We started UBC AI Safety hoping to get 1-3 students excited about the field. Instead, we ran programs for 50+ participants, built a 12-person leadership team, and established the first visible AI safety presence at our university.

In our experience, university group organizing doesn’t reliably change students’ career plans, nor is it the most efficient use of an experienced AI safety researcher’s time. But it could be a great decision if you're early in your AI safety journey, want to build a community where none exists, or learn by teaching. For us, organizing was the entry point that connected us to the broader field, and we’re proud of what we built.

We're passing off UBC AI Safety to capable successors and moving on to direct work in AI safety. AI safety moves fast, and what worked (or didn’t) for us might not apply next year. If you're starting a group, steal what's useful from this post, ignore what isn't, and share your own lessons when you're done.

If you have questions or feedback, you can reach out to us at ubcaisafety@gmail.com

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Neav Topaz, Rebecca Baron, Sana Shams, Justice Sefas, Chris Tardy, Amy Au, Dong Chen, Rishika Bose, and Vassil Tashev for your feedback and contributions on earlier drafts of this post.

- ^

What does “really excited” mean? What is “high-quality”? What counts as “working on AI safety”?

- ^

On a five-point scale from Strongly disagree to Strongly agree.

- ^

This is data from the first semester only; I (Josh) forgot to do this in the second semester… Gah.

- ^

The Pathfinder Fellowship now provides funding as part of the program.

- ^

An advantage of the AI Safety Atlas over using a combination of materials from various sources is that the difficulty of each chapter is relatively consistent. A challenge with education is that in a given classroom, some students will be bored while others are lost. BlueDot Impact might assign a simple blog post followed by a technical paper, leaving individual students both bored and lost depending on the specific reading. On the other hand, a couple of students said in our feedback forms that they wanted a variety of readings because they wanted to hear different perspectives on AI safety.

- ^

Based on what we hear from other AI safety university groups, it’s normal to get far less interest in second-semester programs. This could be a reason to launch your AI safety group in the first rather than the second semester.

- ^

Justice was a great fit for this role because he takes AI safety seriously, previously participated in MATS, and had time to work through the ARENA curriculum on his own before the program started.

- ^

Abridged version of our launch event plan:

7pm - 7:15pm - Sign in and mingle

7:15pm - 7:30pm - “Jubilee Activity”

We say a statement, e.g., “I am hopeful about the development of AI”, “I feel burnt out trying to keep up with AI news”, and participants spread themselves out on a spectrum from “agree" to "disagree." 3 minutes for discussion with neighbours, and share with the group if time.

7:30pm - 7:45pm - Presentation about AI safety by leadership team

7:45pm - 8:00pm - Food served

8:00pm - 8:30pm - Semi-structured discussion

We scattered pieces of paper with conversation topics around the room and let people choose where to go based on what they wanted to talk about.

8:30 - 9pm - Feedback form, group sharing, closing

The “Jubilee Activity” enables quick connections with new people and gives attendees a sense of the opinions or feelings of other people in the room. The presentation aimed to demonstrate the stance of the group, and set the tone for what we are about.

The Jubilee activity was a hit, but the pre-defined topics were less useful than expected. Feel free to use our activities. In any case, the core message is: think about which activities would best foster connections and contribute to your goals.

- ^

We hosted an in-person speaker event with a Zoom speaker and messed up the audio. We wasted 10-15 minutes of everyone’s time fixing the problem during the event. This could have been avoided if we had done a tech rehearsal beforehand.

Executive summary: A reflective, practice-heavy retrospective from the founders of UBC AI Safety reports strong early demand (50+ participants, 12 leaders, active Slack) but modest career conversion, and offers concrete, cautiously framed advice on program design, outreach, operations, and successor planning for university AI safety groups.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.