Mo Putera

Bio

Participation4

I currently work with CE/AIM-incubated charity ARMoR on research distillation, quantitative modelling, consulting, and general org-boosting to support policy advocacy for market-shaping tools to incentivise innovation and ensure access to antibiotics to help combat AMR.

I was previously an AIM Research Program fellow, was supported by a FTX Future Fund regrant and later Open Philanthropy's affected grantees program, and before that I spent 6 years doing data analytics, business intelligence and knowledge + project management in various industries (airlines, e-commerce) and departments (commercial, marketing), after majoring in physics at UCLA and changing my mind about becoming a physicist. I've also initiated some local priorities research efforts, e.g. a charity evaluation initiative with the moonshot aim of reorienting my home country Malaysia's giving landscape towards effectiveness, albeit with mixed results.

I first learned about effective altruism circa 2014 via A Modest Proposal, Scott Alexander's polemic on using dead children as units of currency to force readers to grapple with the opportunity costs of subpar resource allocation under triage. I have never stopped thinking about it since, although my relationship to it has changed quite a bit; I related to Tyler's personal story (which unsurprisingly also references A Modest Proposal as a life-changing polemic):

I thought my own story might be more relatable for friends with a history of devotion – unusual people who’ve found themselves dedicating their lives to a particular moral vision, whether it was (or is) Buddhism, Christianity, social justice, or climate activism. When these visions gobble up all other meaning in the life of their devotees, well, that sucks. I go through my own history of devotion to effective altruism. It’s the story of [wanting to help] turning into [needing to help] turning into [living to help] turning into [wanting to die] turning into [wanting to help again, because helping is part of a rich life].

How others can help me

I'm looking for "decision guidance"-type roles e.g. applied prioritization research.

How I can help others

Do reach out if you think any of the above piques your interest :)

Posts 4

Comments306

Topic contributions3

I just learned via Martin Sustrik about the late Sofia Corradi,

the spiritual mother of Erasmus, the European student exchange programme, or, in the words of Umberto Eco, “that thing where a Catalan boy goes to study in Belgium, meets a Flemish girl, falls in love with her, marries her, and starts a European family.”

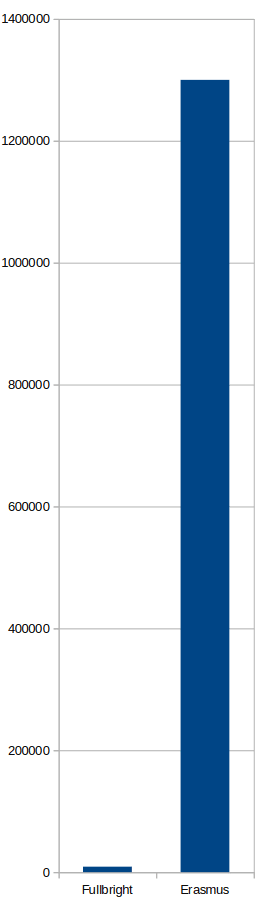

Sustrik points out that none of the glowing obituaries for her mention the sheer scale of Erasmus. The Fulbright in the US is the 2nd largest comparable program, but it's a very distant second:

So far, approximately sixteen million people have taken part in the exchanges. That amounts to roughly 3% or the European population. And with the ever growing participation rates the ratio is going to get even gradually even higher.

Is short, this thing is HUGE.

Sustrik argues that the Erasmus programme is gargantuan-scale social engineering done right:

Substantial portion of students actually does want to spend some time abroad. It’s no different from the Western European marriage pattern, where young people left their parental homes to work as servants, farmhands, or apprentices before they married and set up their own households.

The much-maligned idea of social engineering, in this case, doesn’t mean forcing people to do something they don’t want to do. It means removing the obstacles that prevent them from doing what they already want.

Before Erasmus, studying abroad was seen as having fun rather than as serious academic work, something to be punished rather than rewarded. Universities were reluctant to recognize studies completed elsewhere. Erasmus, with its credit transfer system, changed that and thus unleashed a massive wave of student exchanges.

The backstory to how Sofia came to focus on Erasmus is touching:

In 1957, in her fourth year of studies, she received the opportunity to study in the United States thanks to a Fulbright scholarship. She spent a year at Columbia University where she attended a master’s course in comparative university legislation.[3][4] Upon her return to Rome in 1958, however, her degree was not recognised by the Italian educational system.[4][5] She recalled how she felt humiliated in front of other students as her time in the US was dismissed as a "vacation", and how a functionary had told her "Columbia, you say? I've never heard of that before".[5][6] She had to spend an extra year to obtain her Italian degree.[5] The experience led her to the idea of creating a system of recognition of courses taken abroad and the promotion of university exchanges.[5][7]

Such ideas had already been put forward in Italy, but without any concrete results.[7] After graduating Corradi pursued research on the right to education at the United Nations and became a scientific consultant for the Association of Rectors of Italian Universities at the age of 30.[5][6] It was a post she gained in part to her diploma from Columbia, and she used her position to lobby intensively for her idea of a university exchange programme and mutual recognition. ... (more on Wikipedia)

I've previously wondered what a shortlist of people who've beneficially impacted the world at the scale of ~100 milliBorlaugs might look like, and suggested Melinda & Bill Gates and Tom Frieden. (A "Borlaug" is a unit of impact I made up, it means a billion lives saved.) If you buy Corradi's argument that the Erasmus programme is at heart really a peace programme and that it deserves some credit for the long period of relative peace we've experienced globally post-WWII, then Sofia Corradi seems eminently deserving of inclusion.

Sounds like a cause X, helping people gain clarity on tractable subsets of the general issue you mentioned... although as I write this I realise 80K and Probably Good etc are a thing, their qualitative advice is great, and they've argued against doing the quantitative version. (Some people disagree but they're in the minority and it hasn't really caught on in the couple of years I've paid attention to this.)

Thanks for sharing, really energising to see. Their blog post has really nice illustrations, sharing some of them below.

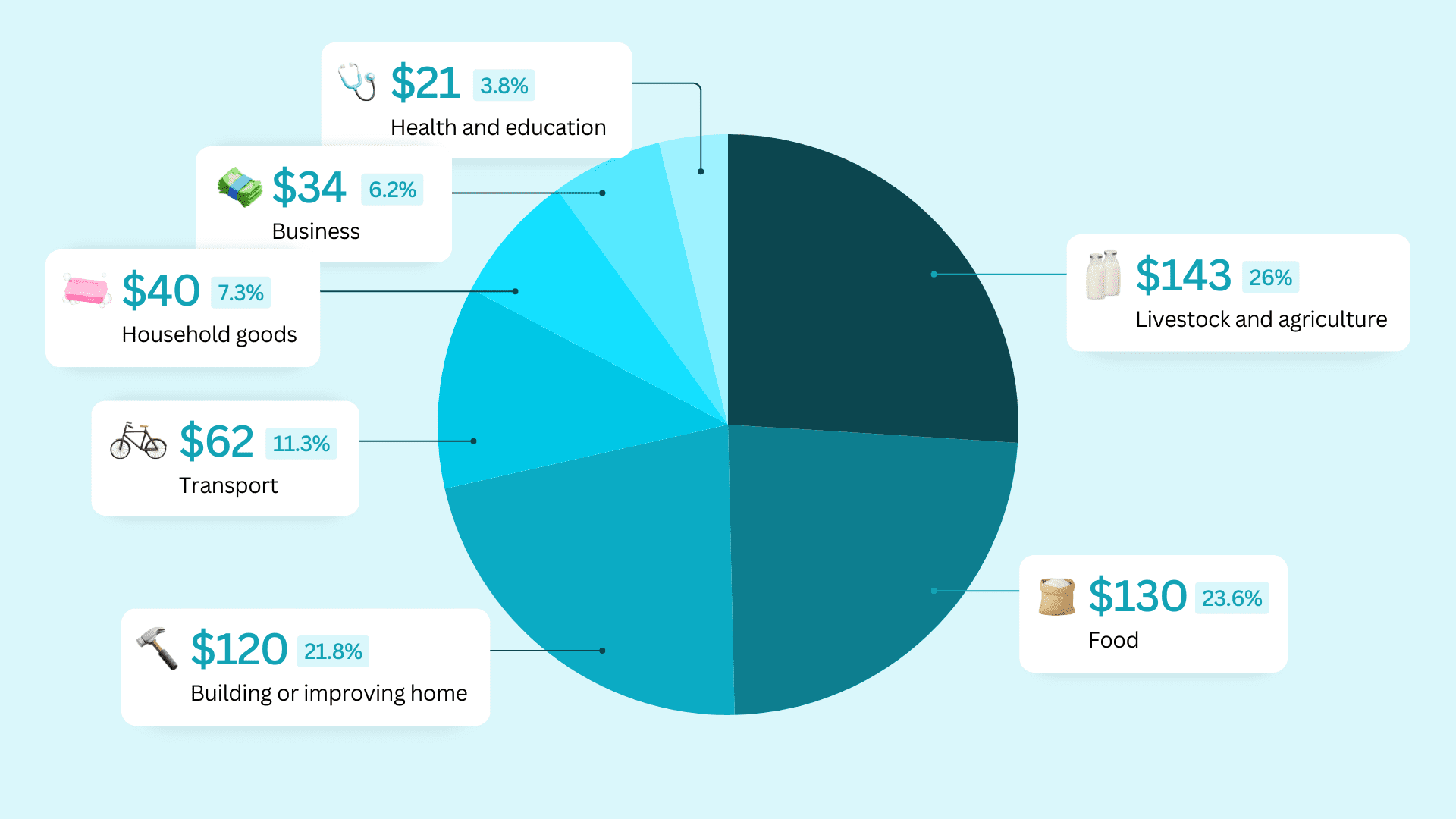

These are some of the results from the $50M they've donated so far to GiveDirectly to every adult in the Khongoni subdistrict of Malawi:

This was what they spent it on:

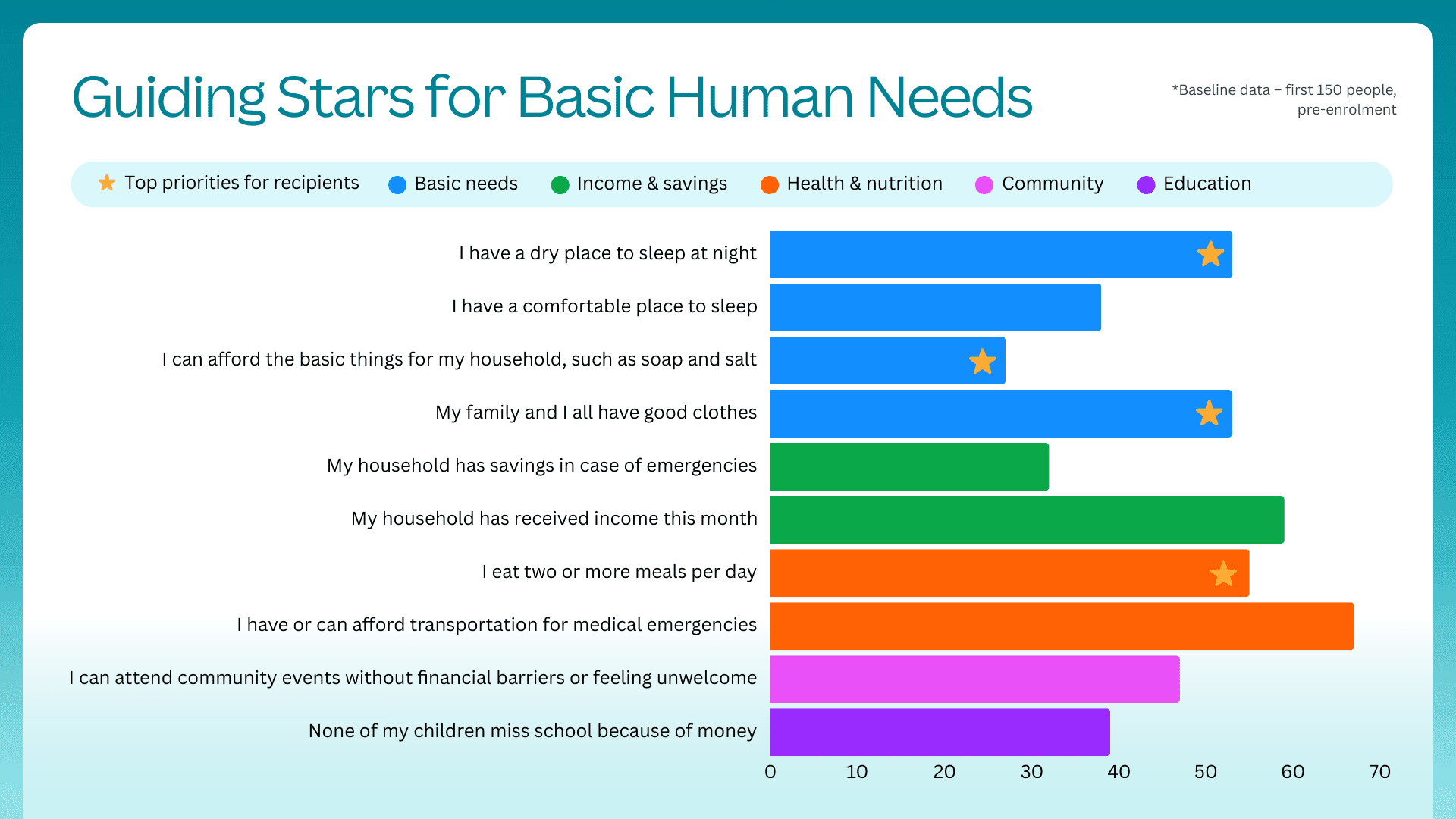

This is the framework Canva came up with to track impact on recipients via continuous surveys:

In the next phase with their $100M commitment to GiveDirectly, these are some of the research questions they're helping GD explore:

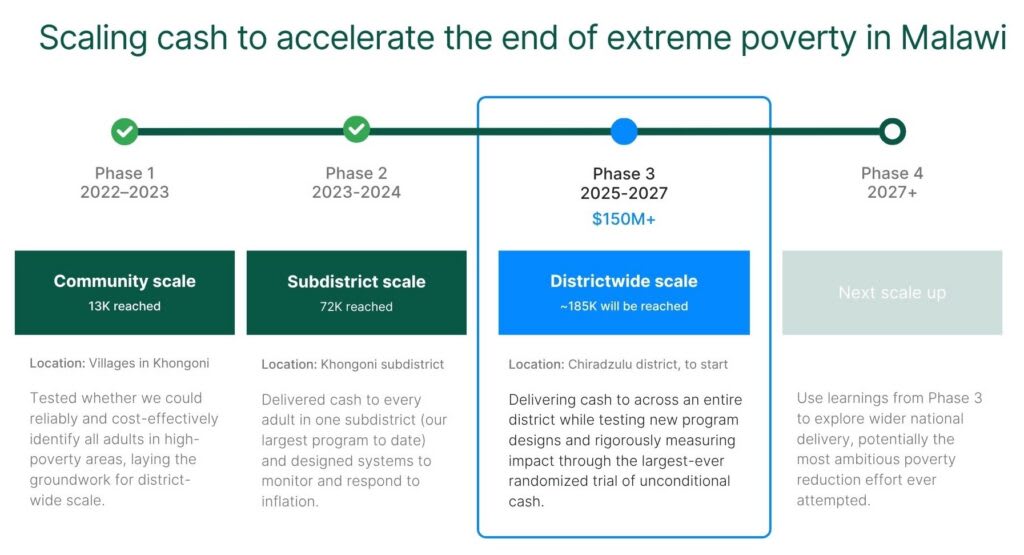

And from GiveDirectly's side of the story — the first 2 phases were funded entirely by Canva:

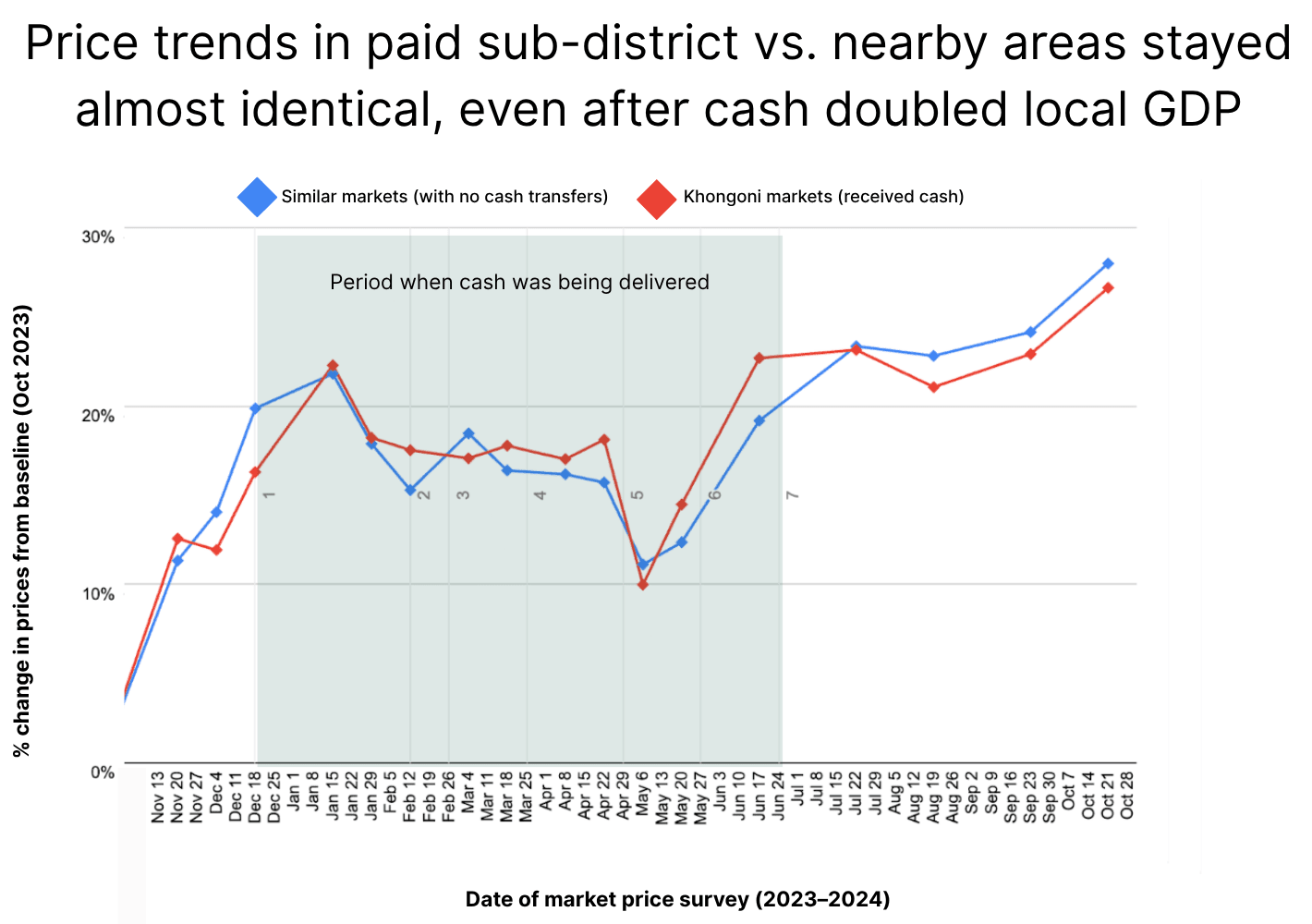

Despite doubling Khongoni's local GDP, inflation was negligible; quoting GD:

Markets were able to absorb large-scale transfers without driving significant price inflation. That gives us strong evidence that this model can be scaled responsibly and rapidly without triggering harmful inflation.

This stability was a product of how recipients and markets responded:

- 🗓️ Recipients didn’t spend all at once: Findings showed households did not spend all of the transfer immediately and gradually increased their spending over months.

- 🚲 They also shopped around: Recipients had access to multiple markets, locally and in nearby Lilongwe city, allowing them to choose between sellers if someone didn’t have what they needed or tried to raise prices.

- 🤝 Vendors chose not to raise prices: Traders reported keeping prices steady to maintain trust, saying opportunistic hikes would damage their reputation once the cash was gone.

- 📦 Markets adapted to demand: Many vendors simply ordered more stock and new traders entered markets, both without significantly driving up prices.

I'm a fan of cash transfers and think it's a tad underrated in EA circles, so I'll end by quoting Canva on cash:

In over 500 randomised controlled trials, direct cash transfers have significantly improved lives:

- Child mortality dropped by 48%, and infant mortality dropped by 57% (Walker et al.,2025) .

- Incomes more than doubled (McIntosh et al., 2023)

- School enrolment rose by 23% (Baird et al., 2014)

- Domestic violence dropped by 3% (Haushofer et al., 2019)

- Illness dropped by 27% (Pega et al., 2017)

- Wellbeing and mental health significantly improved (Zimmerman et al., 2021)

- Economic activity increased by $2.50 for every $1.00 transferred in rural Kenya (Egger et al., 2022)

You might be wondering why cash transfers are able to have an impact in so many different areas. We believe the impact lies in giving people the autonomy to choose what they need most. In all the examples we’ve seen, each person put the money towards ensuring they and their families were able to access their most basic needs while also putting the money to work to generate income in an ongoing manner.

Research shows the cost-effectiveness of cash transfers continues to be elevated upwards to show more impact. Last year, GiveWell reviewed the latest evidence from GiveDirectly and increased their estimates of cost-effectiveness by 3 to 4 times.

You might appreciate these reflections too.

This essay is a reconciliation of moral commitment and the good life. Here is its essence in two paragraphs:

Totalized by an ought, I sought its source outside myself. I found nothing. The ought came from me, an internal whip toward a thing which, confusingly, I already wanted – to see others flourish. I dropped the whip. My want now rested, commensurate, amidst others of its kind – terminal wants for ends-in-themselves: loving, dancing, and the other spiritual requirements of my particular life. To say that these were lesser seemed to say, “It is more vital and urgent to eat well than to drink or sleep well.” No – I will eat, sleep, and drink well to feel alive; so too will I love and dance as well as help.

Once, the material requirements of life were in competition: If we spent time building shelter it might jeopardize daylight that could have been spent hunting. We built communities to take the material requirements of life out of competition. For many of us, the task remains to do the same for our spirits. Particularly so for those working outside of organized religion on huge, consuming causes. I suggest such a community might practice something like “fractal altruism,” taking the good life at the scale of its individuals out of competition with impact at the scale of the world.

(This was a really nice "lightning lit review", do consider saving it on something like a personal site instead of leaving it here :) I've seen a fair number of the writings you cited, but (being a lay outsider) hadn't made sense of the "landscape" they constituted so to speak, why and how they're important, etc until I read your answer here.)

On this note, Probably Good's Civil Service in LMICs as a High-Impact Career Path is a great first stop for EAs from LMICs. Their job board is great too.

Someone could still make that estimate if they wanted to, but nobody has done it.

My impression was Nuno Sempere did a lot of this, e.g. here way back in 2021?

But if ň=1.5, then theory will predict changes on the scale of 0.076x to 0.128x that of the GD experiments. Ie, exactly in the boundary of whether it's possible to detect an effect at all or not!

Might be misreading, on a quick skim Sam Nolan's analysis seemed pertinent but noticed you'd already commented. Sam's reply still seems useful to me, in particular the data here

In London, it was found to be 1.5, in 20 OECD countries, it was found to be about 1.4. James Snowden assumes 1.59.

although none of those countries are low-income so your concern re: OOD generalisation still applies.

Out of curiosity, what do you think of GPT5-medium's attempt at sketching an answer to Seth's request for the "start here to understand my work" post?