Jim Buhler

Bio

Participation4

Also on LessWrong (with different essays).

Posts 20

Comments108

Topic contributions4

This (and references therein) suggests that we should still be clueless about whether (even) ontological longtermism would do more good than harm overall. This is for the same reasons why we should arguably be clueless about other longtermist projects (a position which you seem sympathetic to?).

Curious what you think of this.

How does the paper relate to your Reasons-based choice and cluelessness post? Is the latter just a less precise and informal version of the former, or is there some deeper difference I'm missing?

Interesting.

Well, let me literally take Anthony's first objection and replace the words to make it apply to the Emily case:

There are many different ways of carving up the set of “effects” according to the reasoning above, which favor different strategies. For example: I might say that I’m confident that

an AMF donation saves livesgiving Emily the order to stand down makes her better off, and I’m clueless about its long-term effects overall (of this order, due to cluelessness about which of the terrorist and the child will be shot). Yet I could just as well say I’m confident that there’s some nontrivially likely possible world containing an astronomical number of happy lives (thanks to the terrorist being shot and not the kid), whichthe donationmy order makes less likely via potentiallyincreasing x-riskpreventing the terrorists (and luckily not the kid) from being shot, and I’m clueless about all the other effects overall. So, at least without an argument that some decomposition of the effects is normatively privileged over others, Option 3 won’t give us much action guidance.

When I wrote the comment you responded to, it just felt to me like only the former decomposition was warranted in this case. But, since then, I'm not sure anymore. It surely feels more "natural", but that's not an argument...

Is your intuition strongly that Emily should stand down for option 3 reasons, or merely that Emily should stand down?

The former, although I might ofc be lying to myself.

Nice, thanks. To the extent that, indeed, noise generally washes out our impact over time, my impression is that the effects of increasing human population in the next 100 years on long-term climate change may be a good counterexample to this general tendency.

Not all long-term effects are equal in terms of how significant they are (relative to near-term effects). A ripple on a pond barely lasts, but current science gives us good indications that i) releasing carbon into the atmosphere lingers for tens of thousands of years, and ii) increased carbon in the atmosphere plausibly hugely affects the total soil nematode population (see, e.g., Tomasik's writings on climate change and wild animals)[1]. It is not effects like (i) and (ii) Bernard's post studies, afaict. I don't see why we should extrapolate from his post that there has to be something that makes us mistaken about (i) and/or (ii), even if we can't say exactly what.

- ^

Again, we might have no clue in which direction, but it still does.

Oh ok so you're saying that:

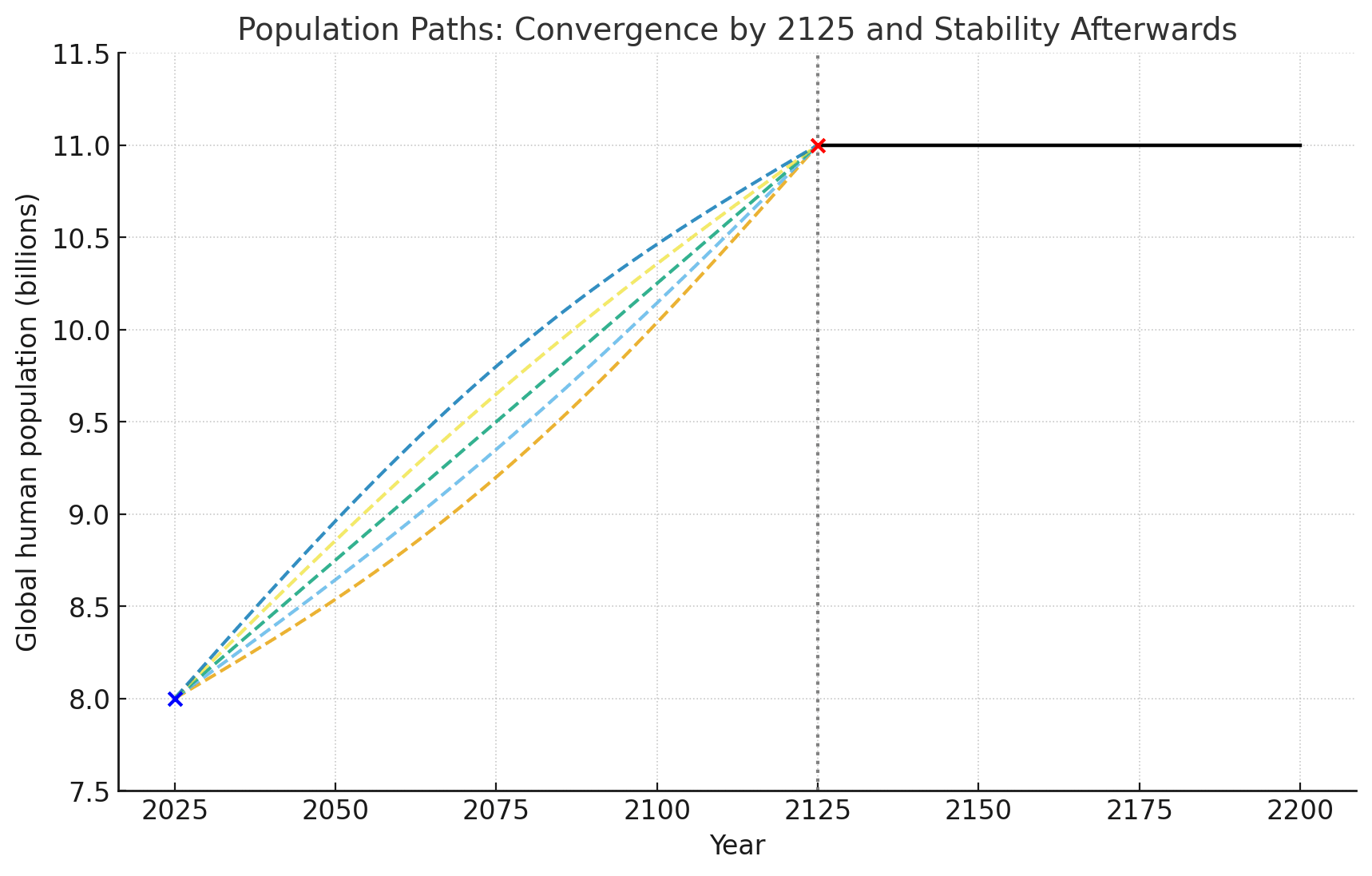

1. In ~100 years, some sort of (almost) unavoidable population equilibrium will be reached no matter how many human lives we (don't) save today. (Ofc, nothing very special in exactly 2125, as you say, and it's not that binary, but you get the point.)

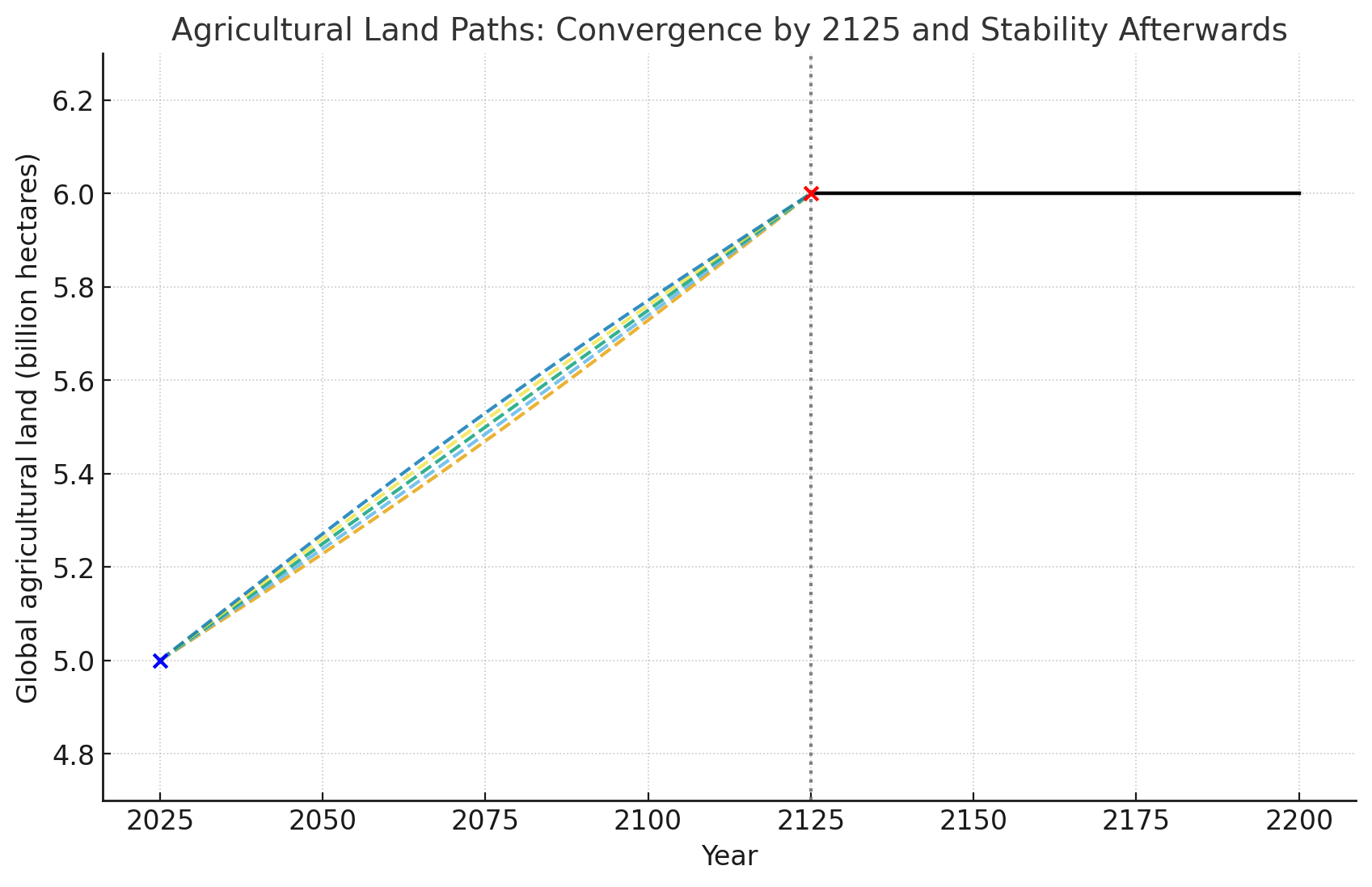

Saving human lives today changes the human population curve between 2025 and ~2125 (multiple possible paths represented by dotted curves). But in ~2125 , our impact (no matter in which direction it was) is canceled out.

2. Even if 1 is a bit false (such that what the above black curve looks like after 2125 actually depends on how many human lives we save today), this won't translate into a difference in terms of agricultural land use (and hence in terms of soil nematode populations).

Almost no matter how many humans there are after ~2125, total agricultural land remains roughly the same.

Is that a fair summary of your view? If yes, what do you make of, say, the climate change implications of changing the total number of humans in the next 100 years? Climate change seems substantially affected by total human population (and therefore by how many human lives we save today). And the total number of soil nematodes seems substantially affected by climate change (e.g., could make a significant difference in whether there will ever be soil nematodes in current dead zones close to the poles), including long after ~2125 (nothing similar to your above points #1 and #2 applies here; climate-change effects last). Given the above + the simple fact that the next 100 years constitute a tiny chunk of time in the scheme of things, the impact we have on soil nematodes counterfactually affected by climate change between ~2125 and the end of time seems to, at least plausibly, dwarf our impact on soil nematodes affected by agricultural land use between now and ~2125.[1] What part of this reasoning goes wrong, exactly, in your view, if any?

- ^

We might have no clue about the sign of our impact on the former such that some would suggest we should ignore it in practice (see, e.g., Clifton 2025; Kollin et al. 2025), but it's a very different thing from assuming this impact almost certainly is negliglble relative to short-term impact.

(Nice, thanks for explaining.) And how do you think saving human lives now impacts the soil nematodes that will be born between 100 years from now and until the end of time? And how does this not dwarf the impact on soil nematodes that will be born in the next 100 years? What happens in 100 years that reduces to pretty much zero the impact of saving human lives now on soil nematodes?

I think empirical evidence suggests effects after 100 years are negligible.

Curious what you think of the arguments given by Kollin et al. (2025), Greaves (2016), and Mogensen (2021) that the indirect effects of donations to AMF/MAWF swamp the intended direct effects. Is it that you agree but you think the unintended indirect effects that swamp the calculus all play out before in 100 years (and the effects beyond that are small enough to be safely neglected)?

But in combination with the principle that we can't understand the downstream effect of our actions in the long-term, I don't understand how somebody can be skeptical of cluelessness.

(You might find this discussion helpful.)

Thanks for the reply :)

> It could eventually make possible the kind of insight you describe (e.g. discovering a selection pressure that would flip X-risk reduction from undefined to positive).

Absolutely, although it could also lead people to mistakenly think they found such insight and do something that turns out bad for the long term. The crux then becomes whether we have any good reason to believe the former is determinately more likely than the latter, despite severe unawareness. To potentially make a convincing case that it is, one really needs to seriously engage with arguments for unawareness-driven cluelessness. Otherwise, one is always gonna give arguments that have already been debunked or that are way too vague for the crux to be identified, and the discussion never advances.