Gregory Lewis🔸

Bio

Mostly bio, occasionally forecasting/epistemics, sometimes stats/medicine, too often invective.

Posts 21

Comments312

FWIW, it's unclear to me how persuasive COVID-19 is as a motivating case for epistemic modesty. I can also recall plenty of egregious misses from public health/epi land, and I expect re-reading the podcast transcript would remind me of some of my own.

On the other hand, the bar would be fairly high: I am pretty sure both EA land and rationalist land had edge over the general population re. COVID. Yet the main battle would be over whether they had 'edge generally' over 'consensus/august authorities'.

Adjudicating this seems murky, with many 'pick and choose' factors ('reasonable justification for me, desperate revisionist cope for thee', etc.) if you have a favoured team you want to win. To skim a few:

- There are large 'blobs' on both sides, so you can pick favourable/unfavourable outliers for any given 'point' you want to score. E.g. I recall in the early days some rationalists having homebrew 'grocery sterilization procedures', and EA buildings applying copper tape, so PH land wasn't alone in getting transmission wrong at first. My guess is in aggregate EA/rationalist land corrected before the preponderance of public health (so 1-0 to them), but you might have to check the (internet) tape on what stuff got pushed and abandoned when.

- Ditto picking and choosing what points to score, how finely to individuate them, or how to aggregate (does the copper tape fad count as a 'point to PH' because they generally didn't get on board as it cancels out all the stuff on handwashing - so 1-1? Or much less as considerably less consequential - 2-1, and surely they were much less wrong about droplets etc., so >3-1?). "Dumbest COVID policies canvassed across the G7 vs. most perceptive metaculus comments" is a blowout, but so too "Worst 'in house' flailing vs. Singapore".

- Plenty of epistemic dark matter to excuse misses. Maybe the copper tape thing was just an astute application of precaution under severe uncertainty (or even mechanistically superior/innovative 'hedging' for transmission route vs. PH-land 'Wash your hands!!') Or maybe 'non-zero COVID' was the right call ex-ante, and the success stories which locked down until vaccine deployment were more 'lucky' (re. vaccines arriving soon enough and the early variants of COVID being NPI-suppressible enough before then) than 'good' (fairly pricing the likelihood of this 'out' and correctly assessing it was worth 'playing to').

- It is surprisingly hard for me to remember exactly what I 'had in mind' for some of my remarks at-the-time, despite the advantage being able to read exactly what I said, and silent variations (e.g, subjective credence behind 'maybe' or mentioning, rationale) would affect the 'scoring' a lot. I expect I would fare much worse in figuring this out for others, still less 'prevailing view of [group] at [date]'

- Plenty of bulveristic stories to dismiss hits as 'you didn't deserve to be right'. "EAs and rationalists generally panicked and got tilted off the face of the planet during COVID, so always advocated for maximal risk aversion - they were sometimes right, but seldom truth-tracking"/ "Authorities tended staid, suppressive of any inconvenient truths, and ineffectual, and got lucky when no action was the best option as well as the default outcome."

- Sometimes what was 'proven right' ex post remains controversial.

For better or worse, I still agree with my piece on epistemic modesty, although perhaps I find myself an increasing minority amongst my peers.

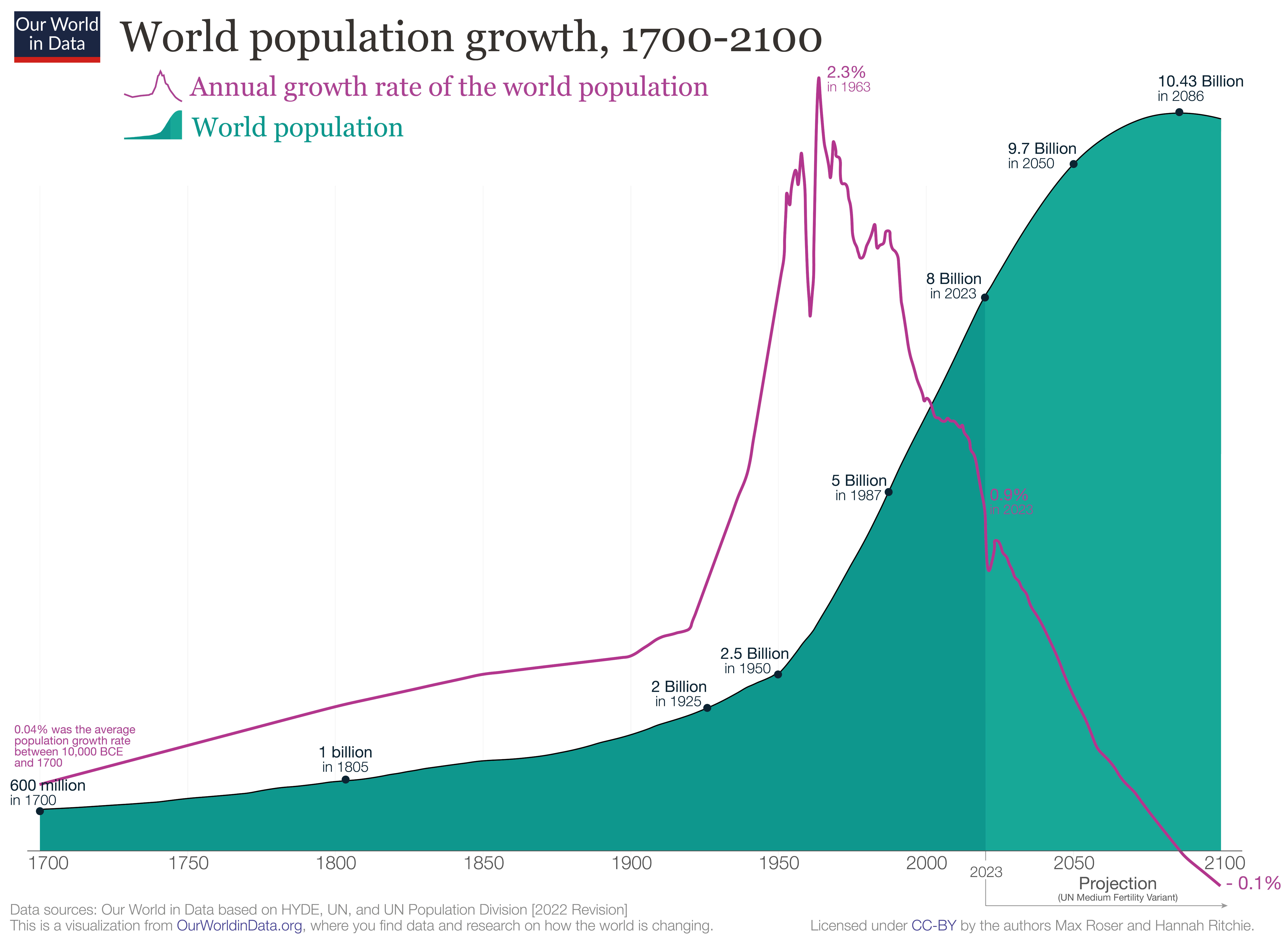

It has? The empirical track record has been slowing global population growth, which peaked 60 years ago:

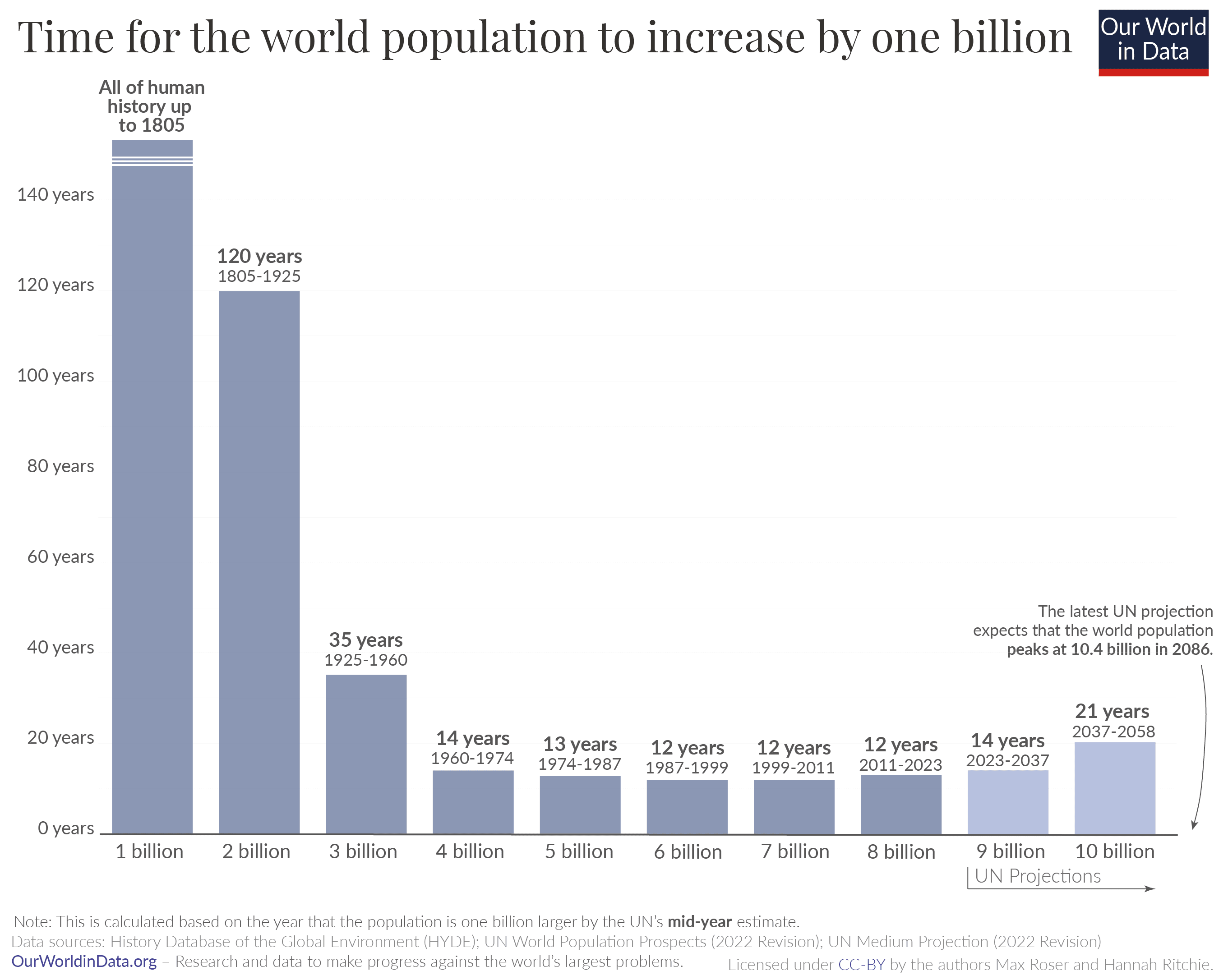

The population itself also looks pretty linear for the last 60 years, given 1B/~12 years rate:

#

I think the general story is something like this:

- The (observable) universe is a surprisingly small place when plotted on a log scale. Thus anything growing exponentially will hit physical ceilings if projected forward long enough: a population of 1000 humans growing at 0.9% pa roughly equal the number of atoms in the universe after 20 000 years.

- (Even uploading digital humans onto computronium only gets you a little further on the log scale: after 60 000 years our population has grown to 2E236, so ~E150 people per atom, and E50 per planck volume. If that number is not sufficiently ridiculous, just let the growth run for a million more years and EE notation starts making sense (10^10^x).)

- There are usually also 'practical' ceilings which look implausible to reach long before you've exhausted the universe: "If this stock keeps doubling in value, this company would be 99% of the global market cap in X years", "Even if the total addressable consumer market is the entire human population, people aren't going to be buying multiple subscriptions to Netflix each.", etc.

- So ~everything is ultimately an S-curve. Yet although 'this trend will start capping out somewhere' is a very safe bet, 'calling the inflection point' before you've passed it is known to be extremely hard. Sigmoid curves in their early days are essentially indistinguishable from exponential ones, and the extra parameter which ~guarantees they can better (over?)fit the points on the graph than a simple exponential give very unstable estimates of the putative ceiling the trend will 'cap out' at. (cf. 1, 2.)

- Many important things turn on (e.g.) 'scaling is hitting the wall ~now' vs. 'scaling will hit the wall roughly at the point of the first dyson sphere data center' As the universe is a small place on a log scale, this range is easily spanned by different analysis choices on how you project forward.

- Without strong priors on 'inflecting soon' vs. 'inflecting late', forecasts tend to be volatile: is this small blip above or below trend really a blip, or a sign we're entering a faster/slow regime?

- (My guess is the right ur-prior favours 'inflecting soon' weakly and in general, although exceptions and big misses abound. In most cases, you have mechanistic steers you can appeal to which give much more evidence. I'm not sure AI is one of them, as it seems a complete epistemic mess to me.)

I think less selective quotation makes the line of argument clear.

Continuing the first quote:

The scenario in the short story is not the median forecast for any AI futures author, and none of the AI2027 authors actually believe that 2027 is the median year for a singularity to happen. But the argument they make is that 2027 is a plausible year, and they back it up with images of sophisticated looking modelling like the following:

[img]

This combination of compelling short story and seemingly-rigorous research may have been the secret sauce that let the article to go viral and be treated as a serious project:

[quote]

Now, I was originally happy to dismiss this work and just wait for their predictions to fail, but this thing just keeps spreading, including a youtube video with millions of views. So I decided to actually dig into the model and the code, and try to understand what the authors were saying and what evidence they were using to back it up.

The article is huge, so I focussed on one section alone: their “timelines forecast” code and accompanying methodology section. Not to mince words, I think it’s pretty bad. It’s not just that I disagree with their parameter estimates, it’s that I think the fundamental structure of their model is highly questionable and at times barely justified, there is very little empirical validation of the model, and there are parts of the code that the write-up of the model straight up misrepresents.

So the summary of this would not be "... and so I think AI 2027 is a bit less plausible than the authors do", but something like: "I think the work motivating AI 2027 being a credible scenario is, in fact, not good, and should not persuade those who did not believe this already. It is regrettable this work is being publicised (and perhaps presented) as much stronger than it really is."

Continuing the second quote:

What I’m most against is people taking shoddy toy models seriously and basing life decisions on them, as I have seen happen for AI2027. This is just a model for a tiny slice of the possibility space for how AI will go, and in my opinion it is implemented poorly even if you agree with the author's general worldview.

The right account for decision making under (severe) uncertainty is up for grabs, but in the 'make a less shoddy toy model' approach the quote would urge having a wide ensemble of different ones (including, say, those which are sub-exponential, 'hit the wall' or whatever else), and further urge we should put very little weight on the AI2027 model in whatever ensemble we will be using for important decisions.

Titotal actually ended their post with an alternative prescription:

I think people are going to deal with the fact that it’s really difficult to predict how a technology like AI is going to turn out. The massive blobs of uncertainty shown in AI 2027 are still severe underestimates of the uncertainty involved. If your plans for the future rely on prognostication, and this is the standard of work you are using, I think your plans are doomed. I would advise looking into plans that are robust to extreme uncertainty in how AI actually goes, and avoid actions that could blow up in your face if you turn out to be badly wrong.

An update:

I'll donate 5k USD if the Ozler RCT reports an effect size greater than d = 0.4 - 2x smaller than HLI's estimate of ~ 0.8, and below the bottom 0.1% of their monte carlo runs.

This RCT (which should have been the Baird RCT - my apologies for mistakenly substituting Sarah Baird with her colleague Berk Ozler as first author previously) is now out.

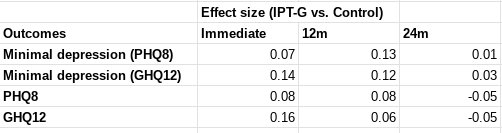

I was not specific on which effect size would count, but all relevant[1] effect sizes reported by this study are much lower than d = 0.4 - around d = 0.1. I roughly[2] calculate the figures below.

In terms of "SD-years of depression averted" or similar, there are a few different ways you could slice it (e.g. which outcome you use, whether you linearly interpolate, do you extend the effects out to 5 years, etc). But when I play with the numbers I get results around 0.1-0.25 SD-years of depression averted per person (as a sense check, this lines up with an initial effect of ~0.1, which seems to last between 1-2 years).

These are indeed "dramatically worse results than HLI's [2021] evaluation would predict". They are also substantially worse than HLI's (much lower) updated 2023 estimates of Strongminds. The immediate effects of 0.07-0.16 are ~>5x lower than HLI's (2021) estimate of an immediate effect of 0.8; they are 2-4x lower than HLI's (2023) informed prior for Strongminds having an immediate effect of 0.39. My calculations of the total effect over time from Baird et al. of 0.1-0.25 SD-years of depression averted are ~10x lower than HLI's 2021 estimate of 1.92 SD-years averted, and ~3x lower than their most recent estimate of ~0.6.

Baird et al. also comment on the cost-effectiveness of the intervention in their discussion (p18):

Unfortunately, the IPT-G impacts on depression in this trial are too small to pass a

cost-effectiveness test. We estimate the cost of the program to have been approximately USD 48 per individual offered the program (the cost per attendee was closer to USD 88). Given impact estimates of a reduction in the prevalence of mild depression of 0.054 pp for a period of one year, it implies that the cost of the program per case of depression averted was nearly USD 916, or 2,670 in 2019 PPP terms. An oft-cited reference point estimates that a health intervention can be considered cost-effective if it costs approximately one to three times the GDP per capita of the relevant country per Disability Adjusted Life Year (DALY) averted (Kazibwe et al., 2022; Robinson et al., 2017). We can then convert a case of mild depression averted into its DALY equivalent using the disability weights calculated for the Global Burden of Disease, which equates one year of mild depression to 0.145 DALYs (Salomon et al., 2012, 2015). This implies that ultimately the program cost USD PPP (2019) 18,413 per DALY averted. Since Uganda had a GDP per capita USD PPP (2019) of 2,345, the IPT-G intervention cannot be considered cost-effective using this benchmark.

I'm not sure anything more really needs to be said at this point. But much more could be, and I fear I'll feel obliged to return to these topics before long regardless.

- ^

The report describes the outcomes on p.10:

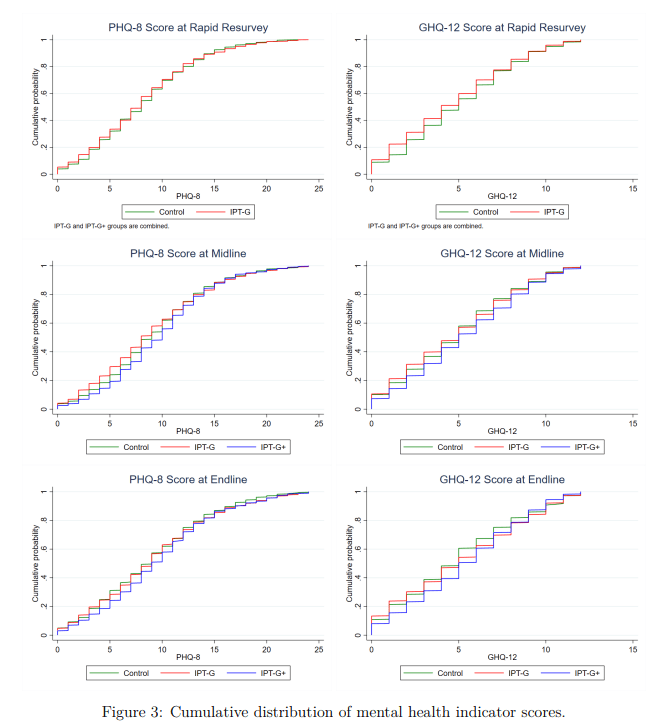

The primary mental health outcomes consist of two binary indicators: (i) having a Patient Health Questionnaire 8 (PHQ-8) score ≤ 4, which is indicative of showing no or minimal depression (Kroenke et al., 2009); and (ii) having a General Health Questionnaire 12 (GHQ-12) score < 3, which indicates one is not suffering from psychological distress (Goldberg and Williams, 1988). We supplement these two indicators with five secondary outcomes: (i) The PHQ-8 score (range: 0-24); (ii) the GHQ-12 score (0-12); (iii) the score on the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (0-30) (Rosenberg, 1965); (iv) the score on the Child and Youth Resilience Measure-Revised (0-34) (Jefferies et al., 2019); and (v) the locus of control score (1-10). The discrete PHQ-8 and GHQ-12 scores allow the assessment of impact on the severity of distress in the sample, while the remaining outcomes capture several distinct dimensions of mental health (Shah et al., 2024).

Measurements were taken following treatment completion ('Rapid resurvey'), then at 12m and 24m thereafer (midline and endline respectively).

I use both primary indicators and the discrete values of the underlying scores they are derived from. I haven't carefully looked at the other secondary outcomes nor the human capital variables, but besides being less relevant, I do not think these showed much greater effects.

- ^

I.e. I took the figures from Table 6 (comparing IPT-G vs. control) for these measures and plugged them into a webtool for Cohen's h or d as appropriate. This is rough and ready, although my calculations agree with the effect sizes either mentioned or described in text. They also pass an 'eye test' of comparing them to the cmfs of the scores in figure 3 - these distributions are very close to one another, consistent with small-to-no effect (one surprising result of this study is IPT-G + cash lead to worse outcomes than either control or IPT-G alone):

One of the virtues of this study is it includes a reproducibility package, so I'd be happy to produce a more rigorous calculation directly from the provided data if folks remain uncertain.

I think the principal challenge for an independent investigation is getting folks with useful information to disclose it, given these people will usually (to some kind and degree) also have 'exposure' to the FTX scandal themselves.

If I was such a person I would expect working with the investigation would be unpleasant, perhaps embarrassing, plausibly acrimonious, and potentially disastrous for my reputation. What's in it for me?

I have previously let HLI have the last word, but this is too egregious.

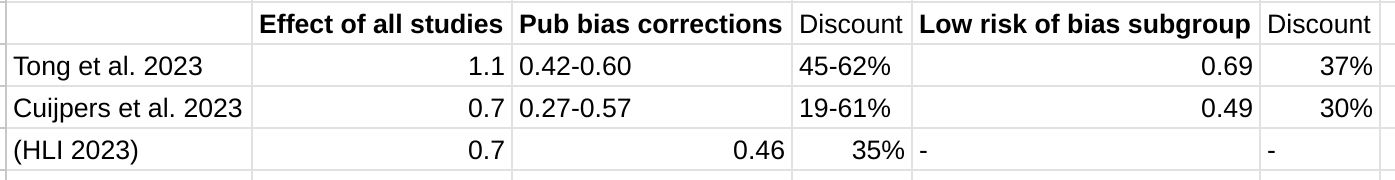

Study quality: Publication bias (a property of the literature as a whole) and risk of bias (particular to each individual study which comprise it) are two different things.[1] Accounting for the former does not account for the latter. This is why the Cochrane handbook, the three meta-analyses HLI mentions here, and HLI's own protocol consider distinguish the two.

Neither Cuijpers et al. 2023 nor Tong et al. 2023 further adjust their low risk of bias subgroup for publication bias.[2] I tabulate the relevant figures from both studies below:

So HLI indeed gets similar initial results and publication bias adjustments to the two other meta-analyses they find. Yet - although these are not like-for-like - these other two meta-analyses find similarly substantial effect reductions when accounting for study quality as they do when assessing at publication bias of the literature as a whole.

There is ample cause for concern here:[3]

- Although neither of these studies 'adjust for both', one later mentioned - Cuijpers et al. 2020 - does. It finds an additional discount to effect size when doing so.[4] So it suggests that indeed 'accounting for' publication bias does not adequately account for risk of bias en passant.

- Tong et al. 2023 - the meta-analysis expressly on PT in LMICs rather than PT generally - finds higher prevalence of indicators of lower study quality in LMICs, and notes this as a competing explanation for the outsized effects.[5]

- As previously mentioned, in the previous meta-analysis, unregistered trials had a 3x greater effect size than registered ones. All trials on Strongminds published so far have not been registered. Baird et al., which is registered, is anticipated to report disappointing results.

Evidentiary standards: Indeed, the report drew upon a large number of studies. Yet even a synthesis of 72 million (or whatever) studies can be misleading if issues of publication bias, risk of bias in individual studies (and so on) are not appropriately addressed. That an area has 72 (or whatever) studies upon it does not mean it is well-studied, nor would this number (nor any number) be sufficient, by itself, to satisfy any evidentiary standard.

Outlier exclusion: The report's approach to outlier exclusion is dissimilar to both Cuijpers et al. 2020 and Tong et al. 2023, and further is dissimilar with respect to features I highlighted as major causes for concern re. HLI's approach in my original comment.[6] Specifically:

- Both of these studies present the analysis with the full data first in their results. Contrast HLI's report, where only the results with outliers excluded are presented in the main results, and the analysis without exclusion is found only in the appendix.[7]

- Both these studies also report the results with the full data as their main findings (e.g. in their respective abstracts). Cuijpers et al. mentions their outlier excluded results primarily in passing ("outliers" appears once in the main text); Tong et al. relegates a lot of theirs to the appendix. HLI's report does the opposite. (cf. fn 7 above)

- Only Tong et al. does further sensitivity analysis on the 'outliers excluded' subgroup. As Jason describes, this is done alongside the analysis where all data included, the qualitative and quantitative differences which result from this analysis choice are prominently highlighted to the reader and extensively discussed. In HLI's report, by contrast, the factor of 3 reduction to ultimate effect size when outliers are not excluded is only alluded to qualitatively in a footnote (fn 33)[8] of the main report's section (3.2) arguing why outliers should be excluded, not included in the reports sensitivity analysis, and only found in the appendix.[9]

- Both studies adjust for publication bias only on all data, not on data with outliers excluded, and these are the publication bias findings they present. Contrast HLI's report.

The Cuijpers et al. 2023 meta-analysis previously mentioned also differs in its approach to outlier exclusion from HLI's report in the ways highlighted above. The Cochrane handbook also supports my recommendations on what approach should be taken, which is what the meta-analyses HLI cites approvingly as examples of "sensible practice" actually do, but what HLI's own work does not.

The reports (non) presentation of the stark quantitative sensitivity of its analysis - material to its report bottom line recommendations - to whether outliers are excluded is clearly inappropriate. It is indefensible if, as I have suggested may be the case, the analysis with outliers included was indeed the analysis first contemplated and conducted.[10] It is even worse if it was the publication bias corrections on the full data was what in fact prompted HLI to start making alternative analysis choices which happened to substantially increase the bottom line figures.

Bayesian analysis: Bayesian methods notoriously do not avoid subjective inputs - most importantly here, what information we attend to when constructing an 'informed prior' (or, if one prefers, how to weigh the results with a particular prior stipulated).

In any case, they provide no protection from misunderstanding the calculation being performed, and so misinterpreting the results. The Bayesian method in the report is actually calculating the (adjusted) average effect size of psychotherapy interventions in general, not the expected effect of a given psychotherapy intervention. Although a trial on Strongminds which shows it is relatively ineffectual should not update our view much the efficacy of psychotherapy interventions (/similar to Strongminds) as a whole, it should update us dramatically on the efficacy of Strongminds itself.

Although as a methodological error this is a subtle one (at least, subtle enough for me not to initially pick up on it), the results it gave are nonsense to the naked eye (e.g. SM would still be held as a GiveDirectly-beating intervention even if there were multiple high quality RCTs on Strongminds giving flat or negative results). HLI should have seen this themselves, should have stopped to think after I highlighted these facially invalid outputs of their method in early review, and definitely should not be doubling down on these conclusions even now.

Making recommendations: Although there are other problems, those I have repeated here make the recommendations of the report unsafe. This is why I recommended against publication. Specifically:

- Although I don't think the Bayesian method the report uses would be appropriate, if it was calculated properly on its own terms (e.g. prediction intervals not confidence intervals to generate the prior, etc.), and leaving everything else the same, the SM bottom line would drop (I'm pretty sure) by a factor a bit more than 2.

- The results are already essentially sensitive to whether outliers are excluded in analysis or not: SM goes from 3.7x -> ~1.1x GD on the back of my envelope, again leaving all else equal.

(1) and (2) combined should net out to SM < GD; (1) or (2) combined with some of the other sensitivity analyses (e.g. spillovers) will also likely net out to SM < GD. Even if one still believes the bulk of (appropriate) analysis paths still support a recommendation, this sensitivity should be made transparent.

- ^

E.g. Even if all studies in the field are conducted impeccably, if journals only accept positive results the literature may still show publication bias. Contrariwise, even if all findings get published, failures in allocation/blinding/etc. could lead to systemic inflation of effect sizes across the literature. In reality - and here - you often have both problems, and they only partially overlap.

- ^

Jason correctly interprets Tong et al. 2023: the number of studies included in their publication bias corrections (117 [+36 w/ trim and fill]) equals the number of all studies, not the low risk of bias subgroup (36 - see table 3). I do have access to Cuijpers et al. 2023, which has a very similar results table, with parallel findings (i.e. they do their publication bias corrections on the whole set of studies, not on a low risk of bias subgroup).

- ^

Me, previously:

HLI's report does not assess the quality of its included studies, although it plans to do so. I appreciate GRADEing 90 studies or whatever is tedious and time consuming, but skipping this step to crack on with the quantitative synthesis is very unwise: any such synthesis could be hugely distorted by low quality studies.

- ^

From their discussion (my emphasis):

Risk of bias is another important problem in research on psychotherapies for depression. In 70% of the trials (92/309) there was at least some risk of bias. And the studies with low risk of bias, clearly indicated smaller effect sizes than the ones that had (at least some) risk of bias. Only four of the 15 specific types of therapy had 5 or more trials without risk of bias. And the effects found in these studies were more modest than what was found for all studies (including the ones with risk of bias). When the studies with low risk of bias were adjusted for publication bias, only two types of therapy remained significant (the “Coping with Depression” course, and self-examination therapy).

- ^

E.g. from the abstract (my emphasis):

The larger effect sizes found in non-Western trials were related to the presence of wait-list controls, high risk of bias, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and clinician-diagnosed depression (p < 0.05). The larger treatment effects observed in non-Western trials may result from the high heterogeneous study design and relatively low validity. Further research on long-term effects, adolescent groups, and individual-level data are still needed.

- ^

Apparently, all that HLI really meant with "Excluding outliers is thought sensible practice here; two related meta-analyses, Cuijpers et al., 2020c; Tong et al., 2023, used a similar approach" [my emphasis] was merely "[C]onditional on removing outliers, they identify a similar or greater range of effect sizes as outliers as we do." (see).

Yeah, right.

I also had the same impression as Jason that HLI's reply repeatedly strawmans me. The passive aggressive sniping sprinkled throughout and subsequent backpedalling (in fairness, I suspect by people who were not at the keyboard of the corporate account) is less than impressive too. But it's nearly Christmas, so beyond this footnote I'll let all this slide.

- ^

Me again (my [re-?]emphasis)

Received opinion is typically that outlier exclusion should be avoided without a clear rationale why the 'outliers' arise from a clearly discrepant generating process. If it is to be done, the results of the full data should still be presented as the primary analysis

- ^

Said footnote:

If we didn’t first remove these outliers, the total effect for the recipient of psychotherapy would be much larger (see Section 4.1) but some publication bias adjustment techniques would over-correct the results and suggest the completely implausible result that psychotherapy has negative effects (leading to a smaller adjusted total effect). Once outliers are removed, these methods perform more appropriately. These methods are not magic detectors of publication bias. Instead, they make inferences based on patterns in the data, and we do not want them to make inferences on patterns that are unduly influenced by outliers (e.g., conclude that there is no effect – or, more implausibly, negative effects – of psychotherapy because of the presence of unreasonable effects sizes of up to 10 gs are present and creating large asymmetric patterns). Therefore, we think that removing outliers is appropriate. See Section 5 and Appendix B for more detail.

The sentence in the main text this is a footnote to says:

Removing outliers this way reduced the effect of psychotherapy and improves the sensibility of moderator and publication bias analyses.

- ^

Me again:

[W]ithout excluding data, SM drops from ~3.6x GD to ~1.1x GD. Yet it doesn't get a look in for the sensitivity analysis, where HLI's 'less favourable' outlier method involves taking an average of the other methods (discounting by ~10%), but not doing no outlier exclusion at all (discounting by ~70%).

- ^

My remark about "Even if you didn't pre-specify, presenting your first cut as the primary analysis helps for nothing up my sleeve reasons" which Dwyer mentions elsewhere was a reference to 'nothing up my sleeve numbers' in cryptography. In the same way picking pi or e initial digits for arbitrary constants reassures the author didn't pick numbers with some ulterior purpose they are not revealing, reporting what one's first analysis showed means readers can compare it to where you ended up after making all the post-hoc judgement calls in the garden of forking paths. "Our first intention analysis would give x, but we ended up convincing ourselves the most appropriate analysis gives a bottom line of 3x" would rightly arouse a lot of scepticism.

I've already mentioned I suspect this is indeed what has happened here: HLI's first cut was including all data, but argued itself into making the choice to exclude, which gave a 3x higher 'bottom line'. Beyond "You didn't say you'd exclude outliers in your protocol" and "basically all of your discussion in the appendix re. outlier exclusion concerns the results of publication bias corrections on the bottom line figures", I kinda feel HLI not denying it is beginning to invite an adverse inference from silence. If I'm right about this, HLI should come clean.

So the problem I had in mind was in the parenthetical in my paragraph:

To its credit, the write-up does highlight this, but does not seem to appreciate the implications are crazy: any PT intervention, so long as it is cheap enough, should be thought better than GD, even if studies upon it show very low effect size (which would usually be reported as a negative result, as almost any study in this field would be underpowered to detect effects as low as are being stipulated)

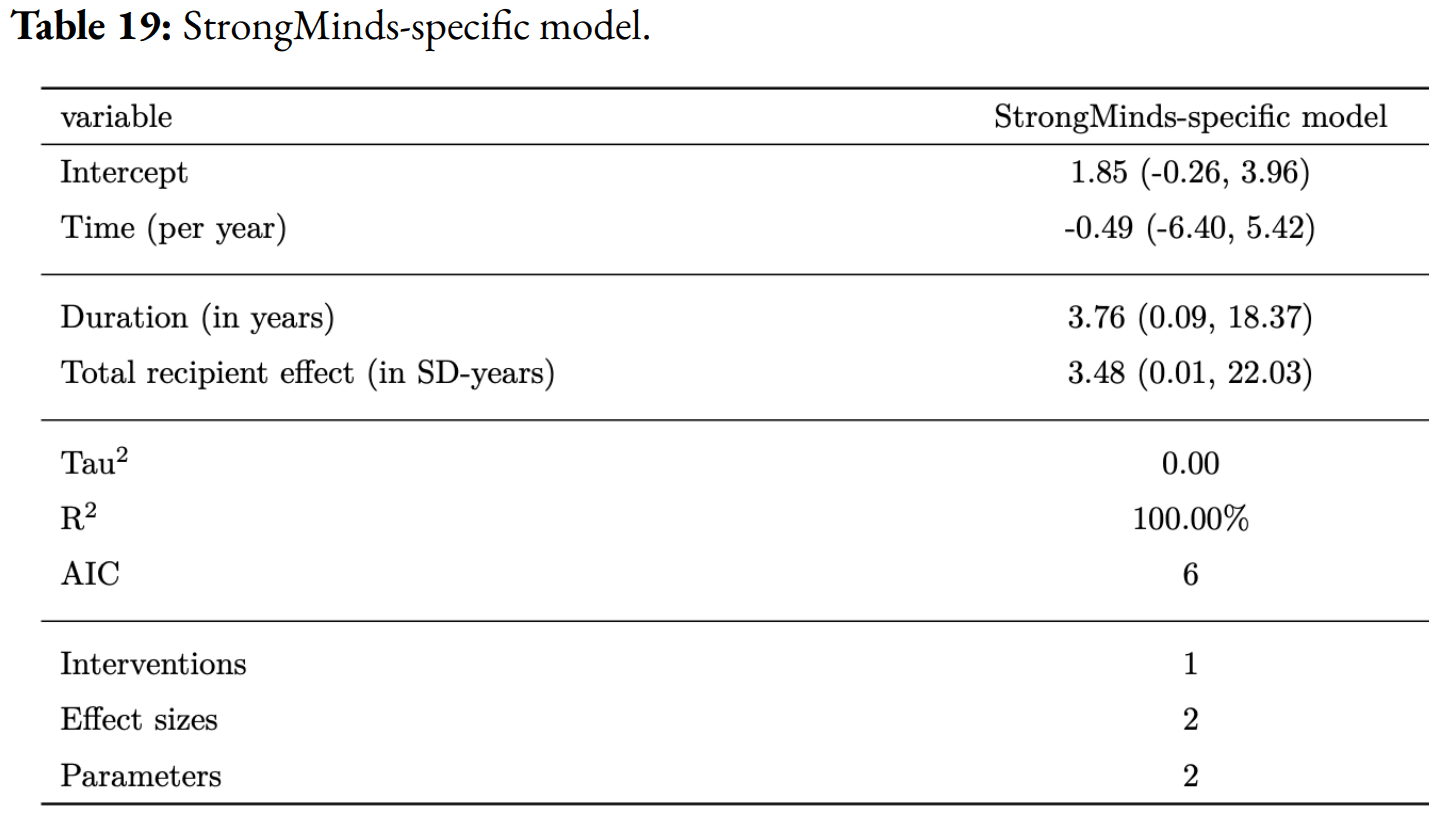

To elaborate: the actual data on Strongminds was a n~250 study by Bolton et al. 2003 then followed up by Bass et al. 2006. HLI models this in table 19:

So an initial effect of g = 1.85, and a total impact of 3.48 WELLBYs. To simulate what the SM data will show once the (anticipated to be disappointing) forthcoming Baird et al. RCT is included, they discount this[1] by a factor of 20.

Thus the simulated effect size of Bolton and Bass is now ~0.1. In this simulated case, the Bolton and Bass studies would be reporting negative results, as they would not be powered to detect an effect size as small as g = 0.1. To benchmark, the forthcoming Baird et al. study is 6x larger than these, and its power calculations have minimal detectable effects g = 0.1 or greater.

Yet, apparently, in such a simulated case we should conclude that Strongminds is fractionally better than GD purely on the basis of two trials reporting negative findings, because numerically the treatment groups did slightly (but not significantly) better than the control ones.

Even if in general we are happy with 'hey, the effect is small, but it is cheap, so it's a highly cost-effective intervention', we should not accept this at the point when 'small' becomes 'too small to be statistically significant'. Analysis method + negative findings =! fractionally better in expectation vs. cash transfers, so I take it as diagnostic the analysis is going wrong.

- ^

I think 'this' must be the initial effect size/intercept, as 3.48 * 0.05 ~ 1.7 not 3.8. I find this counter-intuitive, as I think the drop in total effect should be super not sub linear with intercept, but ignore that.

(@Burner1989 @David Rhys Bernard @Karthik Tadepalli)

I think the fundamental point (i.e. "You cannot use the distribution for the expected value of an average therapy treatment as the prior distribution for a SPECIFIC therapy treatment, as there will be a large amount of variation between possible therapy treatments that is missed when doing this.") is on the right lines, although subsequent discussion of fixed/random effect models might confuse the issue. (Cf. my reply to Jason).

The typical output of a meta-analysis is an (~) average effect size estimate (the diamond at the bottom of the forest plot, etc.) The confidence interval given for that is (very roughly)[1] the interval we predict the true average effect likely lies. So for the basic model given in Section 4 of the report, the average effect size is 0.64, 95% CI (0.54 - 0.74). So (again, roughly) our best guess of the 'true' average effect size of psychotherapy in LMICs from our data is 0.64, and we're 95% sure(*) this average is somewhere between (0.54, 0.74).

Clearly, it is not the case that if we draw another study from the same population, we should be 95% confident(*) the effect size of this new data point will lie between 0.54 to 0.74. This would not be true even in the unicorn case there's no between study heterogeneity (e.g. all the studies are measuring the same effect modulo sampling variance), and even less so when this is marked, as here. To answer that question, what you want is a prediction interval.[2] This interval is always wider, and almost always significantly so, than the confidence interval for the average effect: in the same analysis with the 0.54-0.74 confidence interval, the prediction interval was -0.27 to 1.55.

Although the full model HLI uses in constructing informed priors is different from that presented in S4 (e.g. it includes a bunch of moderators), they appear to be constructed with monte carlo on the confidence intervals for the average, not the prediction interval for the data. So I believe the informed prior is actually one of the (adjusted) "Average effect of psychotherapy interventions as a whole", not a prior for (e.g.) "the effect size reported in a given PT study." The latter would need to use the prediction intervals, and have a much wider distribution.[3]

I think this ably explains exactly why the Bayesian method for (e.g.) Strongminds gives very bizarre results when deployed as the report does, but they do make much more sense if re-interpreted as (in essence) computing the expected effect size of 'a future strongminds-like intervention', but not the effect size we should believe StrongMinds actually has once in receipt of trial data upon it specifically. E.g.:

- The histogram of effect sizes shows some comparisons had an effect size < 0, but the 'informed prior' suggests P(ES < 0) is extremely low. As a prior for the effect size of the next study, it is much too confident, given the data, a trial will report positive effects (you have >1/72 studies being negative, so surely it cannot be <1%, etc.). As a prior for the average effect size, this confidence is warranted: given the large number of studies in our sample, most of which report positive effects, we would be very surprised to discover the true average effect size is negative.

- The prior doesn't update very much on data provided. E.g. When we stipulate the trials upon strongminds report a near-zero effect of 0.05 WELLBYs, our estimate of 1.49 WELLBYS goes to 1.26: so we should (apparently) believe in such a circumstance the efficacy of SM is ~25 times greater than the trial data upon it indicates. This is, obviously, absurd. However, such a small update is appropriate if it were to ~the average of PT interventions as a whole: that we observe a new PT intervention has much below average results should cause our average to shift a little towards the new findings, but not much.

In essence, the update we are interested in is not "How effective should we expect future interventions like Strongminds are given the data on Strongminds efficacy", but simply "How effective should we expect Strongminds is given the data on how effective Strongminds is". Given the massive heterogeneity and wide prediction interval, the (correct) informed prior is pretty uninformative, as it isn't that surprised by anything in a very wide range of values, and so on finding trial data on SM with a given estimate in this range, our estimate should update to match it pretty closely.[4]

(This also should mean, unlike the report suggests, the SM estimate is not that 'robust' to adverse data. Eyeballing it, I'd guess the posterior should be going down by a factor of 2-3 conditional on the stipulated data versus currently reported results).

- ^

I'm aware confidence intervals are not credible intervals, and that 'the 95% CI tells you where the true value is with 95% likelihood' strictly misinterprets what a confidence interval is, etc. (see) But perhaps 'close enough', so I'm going to pretend these are credible intervals, and asterisk each time I assume the strictly incorrect interpretation.

- ^

Cf. Cochrane:

The summary estimate and confidence interval from a random-effects meta-analysis refer to the centre of the distribution of intervention effects, but do not describe the width of the distribution. Often the summary estimate and its confidence interval are quoted in isolation and portrayed as a sufficient summary of the meta-analysis. This is inappropriate. The confidence interval from a random-effects meta-analysis describes uncertainty in the location of the mean of systematically different effects in the different studies. It does not describe the degree of heterogeneity among studies, as may be commonly believed. For example, when there are many studies in a meta-analysis, we may obtain a very tight confidence interval around the random-effects estimate of the mean effect even when there is a large amount of heterogeneity. A solution to this problem is to consider a prediction interval (see Section 10.10.4.3).

- ^

Although I think the same mean, so it will give the right 'best guess' initial estimates.

- ^

Obviously, modulo all the other issues I suggest with both the meta-analysis as a whole, that we in fact would incorporate other sources of information into our actual prior, etc. etc.

I'd say my views now are roughly the same now as they were then. Perhaps a bit milder, although I am not sure how much of this is "The podcast was recorded at a time I was especially/?unduly annoyed at particular EA antics which coloured my remarks despite my best efforts (such as they were, and alas remain) at moderation" (the complements in the pre-amble to my rant were sincere; I saw myself as hectoring a minority), vs. "Time and lapses of memory have been a salve for my apoplexy---but if I could manage a full recounting, I would reprise my erstwhile rage".

But at least re. epistemic modesty vs. 'EA/rationalist exceptionalism', what ultimately decisive is overall performance: ~"Actually, we don't need to be all that modest, because when we strike out from "expert consensus" or hallowed authorities, we tend to be proven right". Litigating this is harder still than re. COVID specifically (even if 'EA land' spanked 'credentialed expertise land' re. COVID, its batting average across fields could still be worse, or vice versa),

Yet if I was arguing against my own position, what happened during COVID facially looks like fertile ground to make my case. Perhaps it would collapse on fuller examination, but certainly doesn't seem compelling evidence in favour of my preferred approach on its face.